Note: This is part two of a three part blog post on the Virginia roots of U.S.C.T. soldiers in Missouri regiments.

Part II: Military Service

The 65th and 67th regiments were dispatched in March of 1864 from Missouri to Morganza Bend, Louisiana (a.k.a. Morganzia), a low-lying Mississippi river town nearly thirty miles from Port Hudson; the 62nd, which was sent to Baton Rouge initially, arrived in Morganza in June. Port Hudson had been the scene of a stirring Union victory, in which the U.SC.T. had played a heroic role, in July of 1863. But the Missouri regiments at Morganza saw very little action, aside from some skirmishing by detachments. Their lot was to do garrison duty as an occupation force—building fortifications and gun emplacements, standing guard, cutting roads, repairing levees, and generally maintaining the camp defenses, in an oppressively hot and humid, muddy, mosquito-infested terrain.

Strikingly, eight of the eighteen Albemarle-born men died of disease while in the army. Two of them never made it out of Missouri: the teenagers Jacob Carter and Liberty Carter both died of disease in Benton Barracks on February 17, 1864. Robert Jackson (Carter) died of pneumonia at the General Hospital at Port Hudson on January 15, 1864; Abner Watson (Carter), too, died there, of chronic diarrhea, on June 29, 1864. George Bankhead, who was promoted to corporal on May, 1, 1864, died in the General Hospital in New Orleans August 24, 1864, and Charles Bankhead and Bradford Carter both died at the Regimental Hospital in Morganza on September 26, 1864. William Tucker, who as a member of the 18th U.S.C.T. was deployed to Tennessee rather than to Louisiana, died of inflammation of the bowels in Chattanooga on July 20, 1865.

Benton Barracks and Morganza, the historian Margaret Humphreys has explained, were “two of the deadliest locales of the war,” in terms of the deaths caused by disease; “of the approximately 2,000 Union regiments the 65th USCI had the most deaths from disease.” Pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, measles, typhoid, tuberculosis, scurvy and cholera all took a heavy toll. Moreover, in October of 1864, John David Smith has noted, “a medical military board reported that an undiagnosed disease had ravaged three Missouri black regiments—the 62nd, 65th, and 67th USCT….Sickness wiped out one-third of the enlistees,” or 1,374 of 3,158 men. The 67th’s losses from disease were so acute that it was combined with the 65th U.S.C.T. on July 12, 1865.

Ten of the Albemarle-born men lived to see the Union triumph and the collapse of slavery. Mathew Carter was discharged for disability at Port Hudson, Louisiana on July 10, 1865. Lewis Carter, Winston Jackson (Carter), Warner Carter and Spencer Scott (Carter) all mustered out at Baton Rouge on December 17, 1866, having filled their three-year terms of service. Spencer had worked as a carpenter and preacher in the army. Both he and Winston dropped the name “Carter” and resumed use of their fathers’ surnames (Jackson and Scott respectively) after the war. William J. Carter was promoted to corporal (on April 12, 1865) and mustered out on January 8, 1867. Jackson Carter was also promoted to corporal, on May 1, 1864, and then to sergeant on Sept. 12, 1864; he mustered out of the service on January 8, 1867 in Baton Rouge, having served his full three-year term of enlistment. George Scott mustered out at Camp Parapet near New Orleans on January 19, 1866, while Thomas Brown mustered out in March of 1866. Daniel W. Carter, who enlisted in the 62nd, was promoted to corporal in September of 1864 and served in the color guard. His regiment was transferred to the Texas Gulf Coast late in the war, and participated at the battle of Palmito Ranch there in May of 1865; he mustered at Brownsville, Texas in March of 1866.

The stories of these soldiers call into question some of the accepted wisdom about the U.S.C.T. Typically, scholars describing the regional composition of the U.S.C.T. classify soldiers by the state in which they enlisted; by that measure most black troops came from Louisiana (24,502), Kentucky (23,703) and Tennessee (20,133), and only 5,723 came from Virginia. But if we classify the troops by birthplace, a very different picture emerges, permitting us to see the diasporic nature of the U.S.C.T. The Union’s black regiments reflect an antebellum diaspora driven by the domestic slave trade and involuntary migration, and the wartime diaspora of slaves to Union lines. The state of Virginia, the primary starting place of the interstate slave trade and the source of massive outmigration of antebellum slaveholders to points west, was central to such diaspora. The Carter and Bankhead men were a small sample of more than 230 U.S.C.T. soldiers born in Albemarle County. Albemarle County was one of eleven Virginia counties that had more than 10,000 slaves in 1860; if we extrapolate from these numbers, and imagine that the other large slaveholding counties in Virginia too were the birthplaces of hundreds of slaves who eventually joined the U.S.C.T. ranks, our conclusions about the composition of the U.S.C.T. shift, with Virginia looming large as a beginning point of the journeys of black troops—complex journeys to points of enlistment and then outward again, across the landscape of the Union war.

Back in Missouri, the former masters of these Albemarle-born men experienced reversals of fortune, and, in the case of John Coles Carter, a reverse migration, back to Virginia. As we shall see in the next blog post, John Warner Bankhead and John Coles Carter would claim in 1867 that they had been faithful to the Union cause throughout the Civil War. But that claim is muddied by the fact that their sons Archibald Bankhead, Thomas Bankhead and Charles Edward Carter all fought for the Confederacy (Thomas died during the war). In the spring of 1863, John Coles Carter was arrested by Union militia in Missouri for being a Southern sympathizer. Carter family genealogist Charles Tromblee has offered the plausible theory that Carter was targeted as part of a Union effort to roust out Confederate guerrillas who were using the neighboring Bankhead plantation as a headquarters. Carter was released by Union authorities once the guerrillas left the region, and he was able to get associates to testify to his “faithful loyalty” to the U.S. government. But by January of 1865, with his slaves having fled and emancipation proclaimed in Missouri, he decided he could no longer survive there, and he received permission from Union authorities to go back to Virginia and to throw himself on the support of his family in Albemarle County. When John Coles Carter returned to Missouri in 1867, after two years in Virginia, his claims of loyalty would clash with those of his former slaves, now free men trying to build new lives.

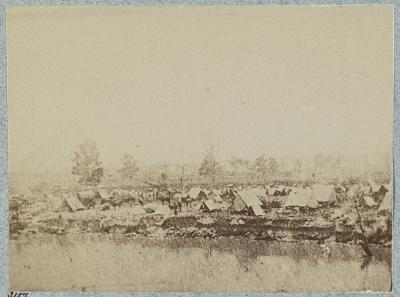

Image: Union Army camp at Morganza Bend, Louisiana (Library of Congress).

Sources: Compiled Service Records, RG 94 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed for each soldier through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Robert Carter, Winston Carter, Warner Carter and Spencer (Scott) Carter, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Charles Tromblee, “John Coles Carter and Family—The Missouri Years” (2012), accessed at Virginia Historical Society; B. Noland Carter II, A Goodly Heritage: A History of the Carter Family in Virginia, Vol. I (2003); Ira Berlin et al., Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (1992); Christian Recorder (Philadelphia), Jan. 30, 1864; William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (2013); Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (2010); John David Smith, ed., Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era (2002); Diane Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Slaveholding Households (2010); Lincoln County (Mo.) Herald, March 12, 1868; Larry M. Logue and Peter Blanck, “’Benefit of the Doubt’: African-American Civil War Veterans and Pensions,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History (Winter 2008).