In October 1913, the Staunton Daily News published an editorial criticizing the lack of attention paid to Virginia students who served in the Union military during the Civil War. In the preceding decade, the University of Virginia had celebrated its Confederate alumni by hosting reunions, casting medals, and dedicating a plaque on the Rotunda. The university had compiled a list of just more than 2,000 Confederate alumni, but it had made no attempt to honor its Union veterans and rarely acknowledged their existence. UVA’s Alumni News reprinted the editorial later that month, acknowledging that “no complete list has been made of the University alumni who saw service in the Union army.”[1]

A century later, the Nau Center is working to create the first definitive list of UVA students who served in the Union military. The fifty-seven students and one professor we have found reflect the diversity of experience of Civil War soldiers and sailors. One was captured and indicted for treason against the Confederacy. One served as colonel of an African-American regiment. One deserted after only two weeks, while another fought for both the Union and the Confederacy. And one, William Meade Fishback, supported radical wartime measures—including emancipation—and led Reconstruction in Arkansas. After the war, however, he became disillusioned with Radical Republicanism and fought to reverse the party’s Reconstruction-era achievements.

Fishback was born in Culpeper County, Virginia, on November 5, 1831, and studied ancient languages at the university from 1852 to 1855. He then read law in Richmond and briefly lived in Springfield, Illinois, where he performed some legal work for Abraham Lincoln. Impressed with the work, Lincoln offered Fishback additional business and assured him he felt “confident you could make a living” in Springfield. Poor health, however, prompted Fishback to move to Arkansas in 1858. He settled near Fort Smith, a town of about 1500 people on the state’s western edge.[2]

Fishback was a staunch Unionist during the secession crisis. When John Brown attacked Harpers Ferry in 1859, Fishback urged Virginia’s governor to pardon him. By showing “mercy and moderation,” he hoped to forge an alliance between northern and southern conservatives against the rising “spirit of fanaticism” in each section. When South Carolina seceded in December 1860, he argued that Congress should “vote every dollar and every man in the United States, if necessary, to force South Carolina to do her duty [to the Union]!” In 1861, he served as a Unionist delegate to the Arkansas Secession Convention. Secessionists denounced him as a “traitor to the South” and threatened to hang him if he attended the convention. Undeterred, he took his seat in Little Rock on March 18 voted to postpone indefinitely a vote on secession.[3]

Unionists held the balance of power in Arkansas until April 1861, when Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion. Unwilling to coerce the seceded states, many Arkansans now prepared to fight the federal government. Fishback reported that “regiments and companies flocked to the governor,” and the state’s unconditional Unionists found themselves unprepared and outnumbered. Fishback attempted to flee the state but encountered secessionists guarding the rivers. The convention president warned him that his life was in “imminent danger” and urged him to “be cautious and silent.” Fearing for his life, he decided to “lend a seeming support to the rebellion.” On May 6, 1861, the convention voted to secede by a vote of 69 to 1, and Fishback sided with the majority.[4]

He attempted to escape again in July but found it “impossible to get through the [Confederate] lines.” Finally, around September 1861, he fled one hundred miles north to Missouri and swore an oath of allegiance to the Union. He returned in 1863, following the Union army as it advanced into Arkansas. That November, he was appointed colonel and began organizing the 4th Arkansas Mounted Infantry, a one-year Union regiment. In December, it reorganized as the three-year 4th Arkansas Cavalry (United States Volunteers). By May 1864, Fishback had recruited roughly 900 men, many of them former Confederate soldiers.[5]

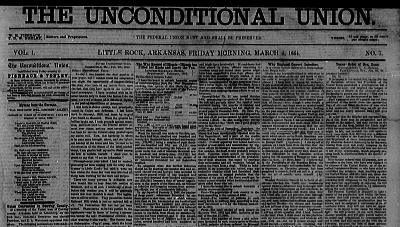

Although he raised the regiment, he never led it into battle. Political duties kept him away, as he worked to restore Arkansas to the Union. Under Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction, a state would be readmitted once ten percent of its 1860 voters had sworn an oath of allegiance and agreed to accept emancipation. In January 1864, Fishback and his allies began drafting a new state constitution, which abolished slavery and repudiated secession. He began publishing a newspaper, The Unconditional Union, to urge voters to ratify the constitution. For Fishback, the Union was “the best government on earth,” sanctified by the “sacred sacrifices which our revolutionary fathers made to establish it.” It was a beacon of hope in a world of oppression, offering the promise of liberty, democracy, and economic opportunity. He defended emancipation, arguing that slavery had hindered Arkansas’s economic development and left its white citizens mired in poverty. He condemned Confederate soldiers for loving “their Cotton or the [Negroe] more than they love their country.”[6]

With Union soldiers monitoring the polls, the required number of Arkansas voters approved the constitution in March 1864. In May, the new Unionist legislature chose Fishback and Elisha Baxter as the state’s United States senators, and Fishback resigned as colonel of the 4th Arkansas Cavalry. Radical Republicans in Congress, however, refused to seat them, believing Lincoln’s ten percent plan for Reconstruction was too lenient. They favored a slow process of Reconstruction that would punish and transform the South. They also questioned Fishback’s loyalty, observing that he had voted for secession in 1861. Senator Charles Sumner argued that Fishback could not take an oath of allegiance without committing perjury. In response, Fishback detailed the threats he had received during the secession crisis, insisting that he would never have “left that convention alive if I had voted against the ordinance [of secession].” Unpersuaded, and unwilling to readmit Arkansas to the Union, the Senate denied Fishback’s and Baxter’s credentials in February 1865.[7]

Unable to take his seat, Fishback returned to Arkansas. After the war he became increasingly critical of Radical Reconstruction. In September 1865, he condemned Radicals’ plans to disenfranchise former Confederates while giving African Americans the right to vote. During the war, he had supported every measure—“however radical or extreme”—that was necessary to preserve the Union. Now, he argued, the question “is not how to make war, but how to make PEACE!” He believed former Confederates should regain their political rights, noting that disenfranchisement only intensified lingering resentment. At the same time, he deemed African-American suffrage “too preposterous to be discussed,” arguing that former slaves were “incapable of taking care of [themselves].” In August 1866, he drew a sharp distinction between war-time Unionists and Radical Republicans. Unionists, he wrote, believed “the Union is indissoluble,” while Radicals insisted “the Union was dissolved by the Rebellion!” Unionists fought to preserve the Union, while Radicals worked to keep it divided and its people oppressed.[8]

Disillusioned with the Republican Party, Fishback served as a Democratic delegate to the state’s 1874 constitutional convention. He tried unsuccessfully to include a provision in the new constitution repudiating the railroad and levee debts incurred under Republican administrations. He then served in the state legislature from 1876 to 1880, continuing to push for what became known as the “Fishback Amendment.” Republican governors blocked the amendment until 1884, when voters approved it by a vote of 119,806 to 15,492. Fishback ran for governor as a Democrat in 1892, easily defeating his Republican and Populist challengers and carrying all but seven of the state’s seventy-five counties. Although he hoped to improve Arkansas’s infrastructure and educational system, the economic depression of the 1890s hindered his legislative agenda. He lost his bid for reelection in 1894 but remained politically active, campaigning for Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan in 1896. He suffered a stroke in early 1903, and died on February 9, at the age of seventy-one.[9]

UVA’s Alumni Bulletin made no mention of his death, a fact that reflected the university’s selective, pro-Confederate memory of the Civil War. The university’s 1878 Semi-Centennial Catalogue—published after Fishback had served in two state conventions and been elected to the Senate—described him simply as a lawyer. The Alumni Bulletin mentioned his service as governor several times, but it ignored his war-time Unionism. UVA Unionists’ experiences during the war varied dramatically, as our next installments will reveal. After the war, however, they shared a common obscurity at UVA. As the university glorified its Confederate past, it constructed a war-time narrative of unity and principle that left no place for its Union soldiers and sailors.[10]

Brian Neumann is a PhD candidate in the Corcoran Department of History at UVA. His research examines the social, political, and ideological dynamics of Unionism in South Carolina during the Nullification Crisis.

Images: (1) William Meade Fishback (courtesy Arkansas State Archives). (2) The masthead of The Unconditional Union, William M. Fishback's wartime newspaper.

Notes:

1. “Neglected Alumni,” Staunton Daily News, 14 October 1893; “Notes and Comments,” University of Virginia Alumni News, 29 October 1913.

2. Catalogues of the University of Virginia, Sessions 29, 30, and 31, available from http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; Abraham Lincoln to William M. Fishback, 19 December 1858, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 3, The Abraham Lincoln Association; “William Meade Fishback,” The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography, ed. Timothy P. Donovan and Willard B. Gatewood, Jr. (Fayetteville: Univ. of Arkansas Press, 1981), 91-92.

3. “Now is the Time,” Thirty-Fifth Parallel (Fort Smith, Arkansas), 11 May 1861; William M. Fishback to James H. Lane, 21 June 1864, Senate Documents, Vol. 189; Journal of Both Sessions of the Convention of the State of Arkansas, 1861 (Little Rock: Johnson and Yerkes, 1861).

4. Fishback to Lane, 21 June 1864; Journal of Both Sessions.

5. Fishback to Lane, 21 June 1864; “William Meade Fishback (1831-1903),” The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, available from http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net; “Claim of Alexander R. Meeks for Pay, Etc.,” Decisions of the Comptroller of the Treasury, Vol. III (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897), 116-117; Georgena Duncan, “Uncertain Loyalties: Dual Enlistment in the Third and Fourth Arkansas Cavalry, USV,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72, no. 4 (2013: 305-32, available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24477386.

6. William Fishback, “Speech of W M Fishback, of Fort Smith, Arkansas,” The Unconditional Union (Little Rock, Arkansas), 23 January 1864; “The Election,” The Unconditional Union, 11 March 1864; “Prospectus,” The Unconditional Union, 23 January 1864.

7. William Fishback, “Col. Fishback’s Farewell Address to his Regiment,” The Unconditional Union, 13 May 1864; “William Meade Fishback,” The Governors of Arkansas, 92; Charles Sumner, “Make Haste Slowly: Irreversible Guaranties,” 13 June 1864, The Works of Charles Sumner, Vol. 9; Fishback to Lane, 21 June 1864.

8. William Fishback, “To the so-called Radical Party of Arkansas,” Little Rock Daily Gazette, 27 September 1865; William Fishback, “Letter from Col. Wm M Fishback, of Arkansas,” Weekly Arkansas Gazette, 11 November 1865; William Fishback, “Letter from Hon. W.M. Fishback,” Daily Arkansas Gazette, 6 September 1866.

9. “William Meade Fishback,” The Governors of Arkansas, 93-95.

10. See, for example, “Haec Olim Meminisse Juvabit,” The Alumni Bulletin of the University of Virginia, Vol. III, No. 4, February 1897; “Our Alma Mater in Texas and the Southwest,” The Alumni Bulletin of the University of Virginia, Vol. IV, No. 1, May 1897; “Governors of States,” Alumni Bulletin of the University of Virginia, Third Series, Vol. I, No. 2, April 1908.