John Brown has endured as a singular figure in the lore of abolitionism, as few could match his combination of zealous madness and physical courage. In the aftermath of Brown’s assault on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in October 1859, he paid for those convictions with his life, as did most of his raiders. But the following half-decade would raise many more opportunities for daring men and women, enslaved and free, to confront slavery — and for fearful planters to root out presumed traitors. One such alleged conspirator was a man named Enos Price. A white stonecutter of slender means living near Blacksburg,[1] Price apparently aimed to turn Virginians against secession via a coordinated slave revolt. What is most remarkable about the Price saga, however, is what happened after his capture. Despite arrest, imprisonment, and indictment, plus the ubiquitous ambient dread about “servile insurrection,” Price fared very differently from Brown — he went on to raise his family in Montgomery County for decades afterward. His story, full of twists, reveals another way that the “Slave Power” unraveled during the tumult of war.

A handful of historians, most notably Daniel B. Thorp, have examined the initial plot that witnesses attributed to Price. According to contemporaries, Price had met with an enslaved man named Washington to organize a murderous rebellion against prominent local slaveholders. Price intended for the scheme to ignite on May 18, 1861, immediately preceding the popular referendum on the decision to secede by the Virginia convention. Two nights prior to the scheduled outbreak, however, the Home Guard seized Price and threw him into jail. The Christiansburg New Star claimed that Washington had “apprize[d] his master of what was going on, and had him with others secreted within hearing distance during the conversation [with Price].” The conversation allegedly included a plan for Washington to spread the word among enslaved people at the four largest nearby plantations. A few months later, Price was indicted and arraigned for “conspiring with slaves to rebel and make insurrection.”[2]

Whether the accusations accurately described Price’s intentions is difficult to verify. Fear of rebellion permeates all slave societies, but the Brown raid, the election of Abraham Lincoln, and the specter of an “abolition war” agitated many white Virginians toward the point of hysteria. The geographic position of Montgomery County within western Virginia did not insulate it from these fears. Black residents, a small number of whom were free, comprised over a fifth of the county population, or nearly 2,500 individuals.[3] This concentration, along with local Unionist whites, provided a sizable base for a hypothetical uprising, and any whisper of a revolt was sure to cause panic among the white majority. Might James H. Otey, the physician-planter to whom Washington had supposedly betrayed Price, have taken advantage of this tension to entrap the stonecutter? Perhaps, but no evidence indicates such a plot. If Otey did misrepresent the situation, he probably only embellished the details. Given the multiple witnesses involved and the lack of an obvious motive for framing Price, the root allegation seems to have been true: Price sought to launch a slave revolt in Montgomery.

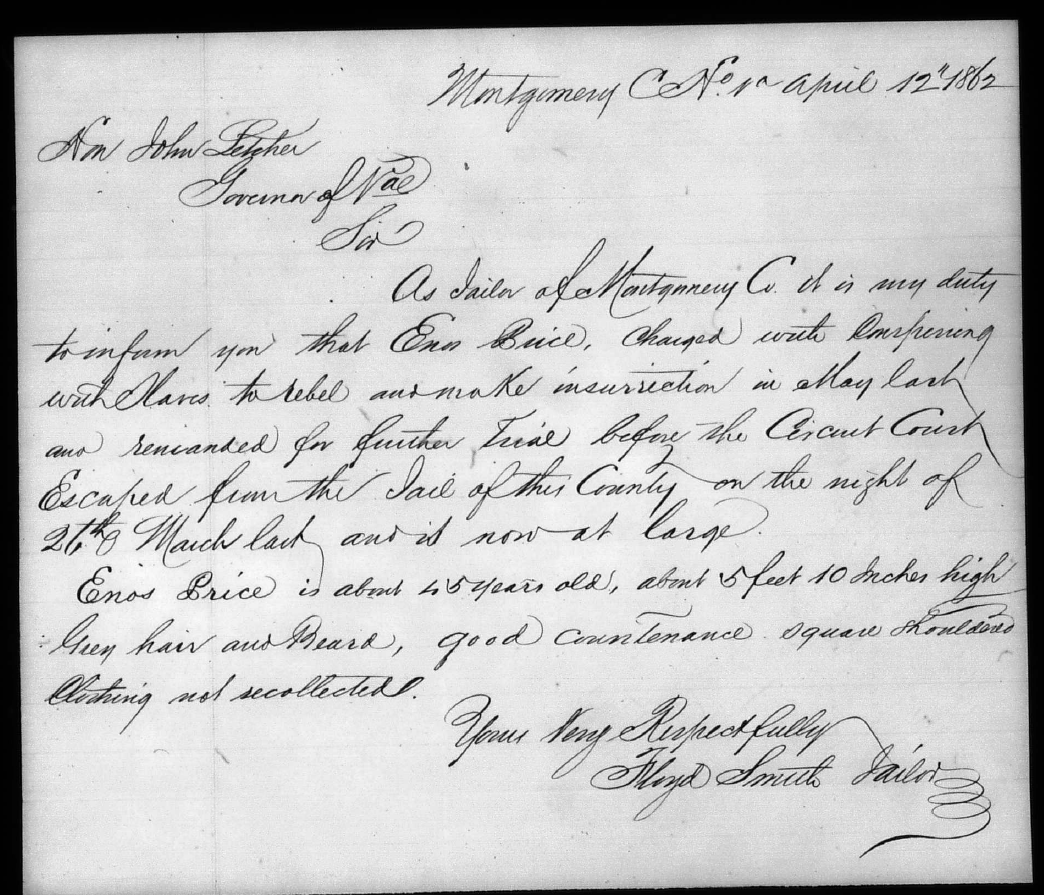

Even if Price was innocent of the charge against him, he must not have felt eager to stand trial in the feverish atmosphere of wartime. If a jury convicted him, the gallows would steal his last breath, as had happened to Brown two years earlier. Yet half a year passed without a trial after Price’s September indictment.[4] The disruption of war and the onset of winter probably slowed the progress of the court, and at some point during this anxious period, Price resolved to escape. On April 12, 1862, the county jailor of Montgomery wrote to Governor John Letcher to report that Price had broken out on the night of March 26 and was “now at large.” The letter also gives a partial portrait of the fugitive: “about 45 years old, about 5 feet 10 Inches high, Grey hair and Beard, good countenance, square shoulders.” As soon as he received the news, the governor declared a $100 reward for the arrest of Price by the public and distributed notice among the Richmond papers. The ads continued appearing into the late summer, but thereafter the search seems to have been lost in the maelstrom.[5]

It seems that Price did not stray too far from Montgomery. He appears as the source of information in county birth records for the March 1863 arrival of a daughter, Charlotte. The annual Montgomery birth registers for 1863 and 1864 were combined, meaning that the report came sometime after January 1, 1865. Legal danger for Price must have abated by the time of this documentation. But the birth indicates that Charlotte’s conception took place in June or July of the previous year, when ads for the capture of her father were still being printed. Unless he was not the biological father, Price must have returned to his wife, Elizabeth, soon after escaping. The couple then lost a four-year-old daughter in October of 1863. They conceived a son in the summer of 1865, and Elizabeth gave birth in early 1866. The couple had the boldness to name the boy Sheridan — a seeming tribute to Philip Sheridan, the Union general who had famously (or, to Confederates, infamously) subdued the Shenandoah Valley at the close of the war. Meanwhile, as the 1870 census indicates, Price returned to work as a stonemason to support his growing family.[6]

It was a stunning turnaround from his imperiled state in the autumn of 1861. To local Confederates, Price had represented the height of wickedness before his jailbreak, and even more so thereafter.[7] Yet he managed to evade the punishing grip of the slaveholders’ law code by taking advantage of wartime chaos. Many questions remain unanswered — Did he live at home during the fighting, or in some hideout? What ultimately became of his legal limbo? Did he ever take up arms as a guerrilla fighter? How strongly attached did he feel to the Lincoln administration? And how did his Montgomery neighbors treat him and his family in the years after Appomattox?

Answers may surface with further research. For now, the Price story reads as the tale of a white Virginian who doubted the endurance of the Confederacy from the very beginning — and found his way through one of the gaps in its armor. His escape suggests that we look more closely for other civilian jailbreaks in the record to evaluate how the war affected criminal trials and incarceration more generally. Finally, with the audacious naming of their son, Enos and Elizabeth Price remind us of that some white Virginians chose to celebrate the Union as they reflected on four years of war.

Jeremy Nelson is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Nau Civil War Center. He received his PhD from the University of Virginia in 2025, and his dissertation was entitled, "Battles of the Wilderness: Ecology, Ideology, and the American Civil War."

Image: Letter from Floyd Smith to John Letcher, April 12, 1862, Executive Papers of Governor John Letcher, 1859-1863, courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

Notes:

[1] In the 1860 census, Price was listed as owning $400 of personal estate and no land. Population Schedules for Montgomery County, Virginia, 1860 Federal Census, Ancestry.com, 129.

[2] Cathleen Carlson Reynolds, “A Pragmatic Loyalty: Unionism in Southwestern Virginia, 1861-1865,” M.A. thesis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1987, Cathleen Carlson Reynolds Manuscript Thesis, Ms-1991-038, Special Collections and University Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 26; Gibson Worsham et al., “Montgomery County Reconnaissance Level Survey,” vol. 1 (July 1986), Virginia Department of Historic Resources, https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/pdf_files/SpecialCollections/MY-057_Montgomery_Co_Recon_Survey_1986_CRMI_report_Vol_I.pdf, 113; Daniel B. Thorp, “‘Learn your wives and daughters how to use the gun and pistol’: The Secession Crisis in Montgomery County, Virginia,” The Smithfield Review 17 (2013): 87–89.

[3] According to the 1860 federal census.

[4] Thorp, “‘Learn your wives’,” 89.

[5] Chapter CXC, The Code of Virginia, 2nd ed., (Ritchie, Dunnavant & Co: 1860), 783; Letter from Floyd Smith to John Letcher, April 12, 1862, Executive Papers of Governor John Letcher, 1859-1863, Box 8, Folder 6, microfilm reel 4764, image 270, Library of Virginia; Richmond Dispatch, April 16, 1862, 3; Richmond Enquirer, April 18, 1862, 3; Richmond Anzeiger, August 2, 1862, 2.

[6] The records provide contradictory information, but it seems quite clear that the woman who later went by Louisa Charlotte [Price] Shealor was born in March 1863. According to the 1863/1864 register of births, the Prices welcomed an unnamed girl in that month. Her four-year-old sister, Elizabeth Sarah or Sarah Elizabeth, died later that October, and the Prices seem to have initially called their new daughter Elizabeth in honor of her. This is the name that appears in the 1870 census, with the middle initial “C.,” probably for “Charlotte.” By 1880, the 17-year-old was listed only as “Charlotte.” After her marriage in 1880, she preferred “Louisa” and kept Charlotte as a middle name. Her birth is marked at “Mar. 1863” in the 1900 census, and the 1910 census gives her age as 47. Although her 1916 death certificate and gravestone list her birthday as March 24, 1862, this was most likely a mistake, given the prior information. See “Sources” tab for Enos Elias Price, Charlotte Louisa Price, Sarah Elizabeth Price, and Sheridan W. Price at FamilySearch.org.

[7] See an example of local outrage in Adam Matthew Jones, “The land of my birth and the home of my heart”: Enlistment Motivations for Confederate Soldiers in Montgomery County, Virginia, 1861-1862,” M.A. thesis, Virginia Tech, 2014, 61, n. 20.