As Americans remove Confederate statues from the public landscape, and debate the symbolism of monuments such as Washington, D.C.’s Emancipation Statue, with its standing Lincoln and kneeling slave, it is instructive to reflect on the paths not taken. As modern scholarship on Civil War memory has noted, African Americans faced daunting obstacles in trying to establish their own public memorials in Jim Crow America. A poignant example is the statue conceived by the National Emancipation Monument Association in 1889. Its design was a striking inverse of the “kneeling slave” motif and a bold rebuttal of the idea that Lincoln bestowed emancipation as a gift. In this monument—which lived a brief evocative life in words and images, though it never took the form of granite and bronze—a black Civil War officer, André Cailloux, stood at the apex with white politicians arrayed at the base. The story of this project, and of its principal champion George W. Bryant, challenges us to reimagine how we remember and represent the Civil War.

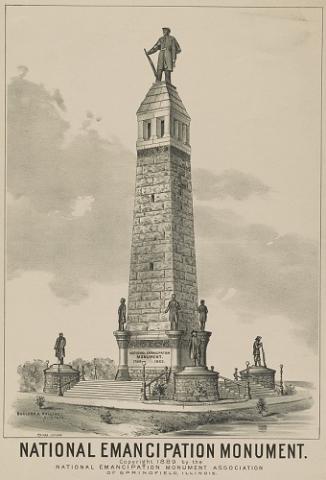

The National Emancipation Monument was the brainchild of a group of African Americans in Springfield, Illinois, led by Republican ward leader and grocer N.B. Smallwood. With the help of a local architectural firm and in consultation with some prominent Republican politicians they devised a design in which a 74-foot plinth (with that number illustrating the number of years, from 1789 to 1863, that the American republic had condoned slavery) would be topped by a giant bronze statue of a black Union soldier. The obelisk’s base would be adorned by smaller statues of eight heroes in the emancipation story: President Abraham Lincoln; white abolitionists Charles Sumner, John Brown, Wendell Phillips, Owen Lovejoy, and William Lloyd Garrison; the iconic black leader Frederick Douglass, and the pioneering black politician Robert Brown Elliott, who served in South Carolina’s Reconstruction-era legislature. The obelisk itself would be inscribed, the Illinois State Journal noted, with “dates and historical incidents connected with the slavery of the colored race in North America.” The project’s progenitors, who formed a corporation called the National Emancipation Monument Association, planned to raise most of the total estimated cost of the monument—$150,000--through donations from black churches and lodges and individual subscriptions. They hoped too to secure some support from the state of Illinois.

Early press coverage of the association’s fundraising efforts for the project emphasized the theme of black gratitude to white deliverers: as the New York Tribune noted in a March 1889 article entitled “Grateful Freedmen,” it was “peculiarly appropriate” that Springfield blacks should “build a monument to the memory of Lincoln, Seward, Sumner, Phillips and John Brown”; Seward was subbed in for Lovejoy in this account, and no mention was made of Douglass and Elliott. The figure standing atop the obelisk was typically characterized as a generic nameless “colored soldier,” who, as the Chicago Tribune put it, “left the menial work of the slavemasters and, acquainting himself with the practice of war, battled for the freedom of himself and loved ones.” Fundraising went slowly at first and the Illinois legislature rejected a bid for a $5000 state appropriation for the project on the grounds that not enough progress had been made from private funds.

The project’s fortunes seemed to improve in 1891 when the association recruited the dynamic George W. Bryant as its principal commissioner and spokesman. Born enslaved in Kentucky in the early 1850s, Bryant escaped to the North through the Underground Railroad, and he eventually made his way to Washington, D.C. where he joined the Union army as a teenager in 1864, serving in the 23rd USCT infantry regiment. After the war he became an A.M.E. minister and a physician, settling in New Orleans and then in St. Louis and Nashville and finally Baltimore. He also was active within the venerable Union veterans’ organization the Grand Army of the Republic, and as a Republican party operative, getting out the vote for candidates such as James Garfield. Most notably, Bryant travelled widely to give speeches on a wide range of religious, historical, and political themes, earning a reputation, as the influential black newspaper the New York Age put it in 1887, as one of the “greatest orators in the South.”

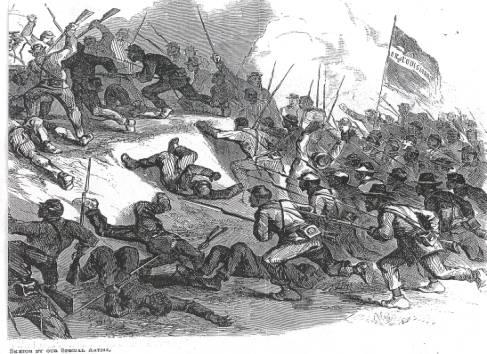

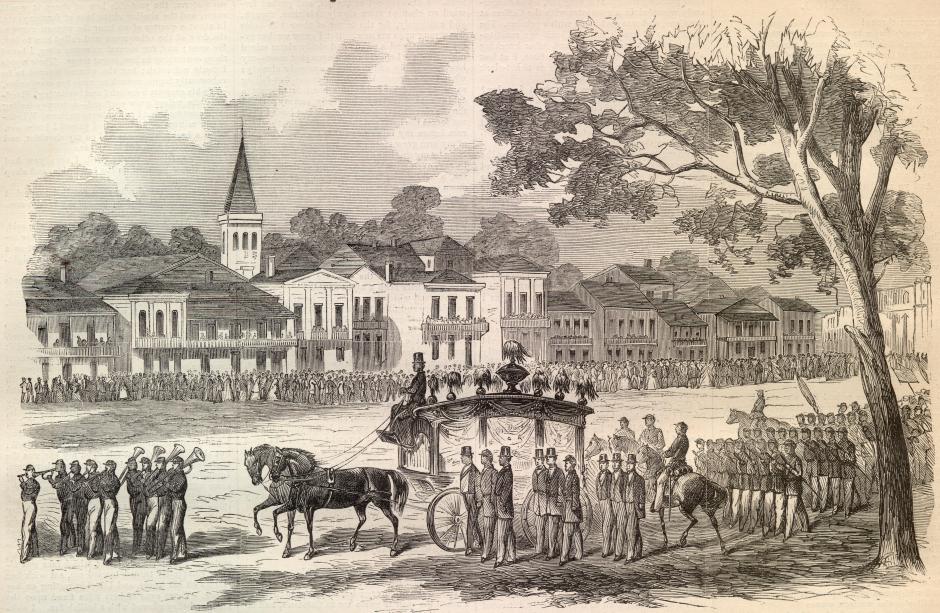

Under Bryant, the monument association became more ambitious in its reach and bolder in its message. As he travelled across the country giving fundraising lectures and organizing auxiliaries in states including Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts, Bryant told his audiences that the memorial was not only a tribute to emancipation but expressly a “monument to colored veterans,” and to one man in particular: Captain André Cailloux. It was Cailloux whose form, cast in bronze, would grace the top of the obelisk. Whether it had always been the intention of the designers to model the crowning statue after Cailloux or whether this was Bryant’s own intervention remains unclear. But the symbolism of this choice was unmistakable. Cailloux, a formerly enslaved artisan who entered the ranks of New Orleans’ distinctive class of gens de couleur libre before the war, died in battle leading a brave though futile charge against Confederate defenses at Port Hudson, Louisiana in May of 1863. With his conspicuous valor, the martyred Cailloux became the first African-American military hero of the war, his sacrifices celebrated in newspaper articles, poems, and in a massive funeral procession in Union-occupied New Orleans.

Cailloux represented the small but influential vanguard of black commissioned officers in the Union army, the vast majority of whom were drawn from New Orleans’ Afro-Creole milieu and served in Louisiana regiments. The approximately 110 African American men who were commissioned at the rank of lieutenant or above made their mark. Although Cailloux fell in battle, and although his fellow black officers in Louisiana regiments were soon purged from the Union army rolls on the grounds that black men should not wield the power to command whites, Cailloux’s comrades-in-arms held up his heroism as a vindication. The purged officers of the Louisiana Native Guards would form a political phalanx, leading the charge for civil rights. In the spring of 1864, they petitioned Lincoln and the Congress to enfranchise black men in Louisiana; Lincoln followed up by writing his now famous March 13, 1864 letter to Louisiana governor Michael Hahn suggesting that black veterans could perhaps be granted the right to vote. In the fall of 1864, Port Hudson veteran Captain James H. Ingraham invoked Cailloux’s memory as a source of inspiration for the delegates to the National Negro Convention in Syracuse, N.Y., as they founded the National Equal Rights League. Cailloux’s name reverberated in black politics for decades: G.A.R. and Equal Rights League chapters were named after him, and his praises were sung by leading black intellectuals such as William Wells Brown and George Washington Williams.

The story of Cailloux exemplified black men’s fitness for leadership at the national level. This was Bryant’s message as he travelled his fundraising circuit, promoting the monument at Emancipation Day ceremonies and Grand Army of the Republic gatherings. Bryant and the association set their sights on the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicago’s massive World’s Fair, proposing to the white managers of the massive celebration that the statue should be erected at the Jackson Park fairgrounds, or, failing that, that a smaller-scale facsimile model of the statue should be displayed at the exposition. By the summer of 1892 the association had raised $65,000 of the necessary $150,000.

But in the following two years, the project lost steam and faded from sight. There is no indication that the memorial facsimile was ever displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair. One of the very last mentions of the monument in the press was a September 2, 1894 article in the black newspaper the Sacramento Bee, entitled “Liberty’s Monument.” The article described the memorial’s design, emphasizing that “the crowning statue will be a bronze representation of Captain André Cailloux and will be thirty feet high. The Captain was one of the bravest soldiers in the entire Union army, and even at the time of his death, at the battle of Port Hudson, after he had been shot twenty-six times, he seized the regimental colors from a dying color guard and held them aloft, sending back word to his colonel that the colors had not been in the dust.” Here was a powerful image not of a grateful slave who was gifted freedom but of a heroic leader who helped save the republic.

So why was “Liberty’s Monument” never finished? The financial obstacles were clearly daunting: the price tag for the monument was very high, and the Springfield location would have been inaccessible to most. We can glean additional clues from Bryant’s own travails. Signs of trouble began to emerge in 1892 when support promised by prominent whites failed to materialize. That July, a major event at Irving Park, Maryland, to celebrate emancipation, proved a setback as honored guests—including President Benjamin Harrison and Republican vice presidential nominee Whitelaw Reid—failed to show up. Later that summer, some newspapers circulated rumors that Bryant was a fraud, collecting donations under false pretenses—the president of the monument association, N.B. Smallwood, tried to stamp the scurrilous gossip out, confirming that Bryant was “the duly accredited agent of the association and is authorized to make collections for it,” but the rumors may have damaged his cause nonetheless.

The broader context for these setbacks was the acute crisis in race relations that unfolded at the very moment Bryant was promoting the monument. As the scourges of lynching, disfranchisement, and Jim Crow segregation engulfed the South, Bryant used his bully pulpit to speak out against white supremacist terrorism. At a June 1892 mass meeting in Boston’s Tremont Temple, protesting against lynching and “demanding the punishment of the perpetrators,” Bryant thundered “the praying time is over, and the reaping time is near at hand” and that if blacks “could not find a Lincoln or Seward in the north they could and would find a black John Brown in the south.” Six months later, at a January 1, 1893, event in Philadelphia to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, Bryant arraigned “the press, the pulpit, and many of the State Legislatures” of the North for “lacking the moral courage to defend their black brethren of the South from being burned alive, flogged and lynched without semblance of law.” In the face of rampant anti-black proscription and violence, surely it seemed to many of Bryant’s listeners that survival and self-defense and political action were more urgent priorities than building statues. Bryant increasingly turned his attention to party politics, intent on the electoral defeat of Southern Democrats. When he died in 1901, the story of the National Emancipation Monument Association died with him.

Ultimately, the most important explanation for why the Springfield Emancipation Monument was never built can be found in the influential 1893 pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition by Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn, and Ferdinand L. Barnett. Addressing the broad policy of racial exclusion at the Fair, Douglass observed, “We have long had in this country, a system of iniquity which possessed the power of blinding the moral perception, stifling the voice of conscience . . . That system was American slavery. Though it is now gone, its essential spirit remains.” Douglass and his fellow authors recognized that they would be censured for dwelling on America’s sins at a moment of national pride and celebration. But they asked their readers to be seekers of the truth.

Perhaps it would have been more pragmatic for George W. Bryant, as he sought white allies for the emancipation monument project, to emphasize the themes of black gratitude and sectional reconciliation—to sing the praises of Lincoln rather than Cailloux. But Bryant chose to be a seeker of the truth. Perhaps he reckoned that if, like Cailloux had, he fought this losing battle with conspicuous bravery, he would help the righteous ultimately to win the war.

Images: National Emancipation Monument (courtesy Library of Congress); (2) André Callioux at the Battle of Port Hudson, (3) André Callioux’s Funeral Procession (courtesy Wikicommons).

Sources: “National Emancipation Monument (Proposed),” SangamonLink, May 7, 2019, https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=11339; Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, 2018), pp. 188-191. For early coverage of the monument project, see for example Dixon Sun (Ill.), March 20, 1889; Bloomington Daily Leader (Ill.), Oct. 11, 1889; Chicago Tribune, Nov. 16, 1889; Inter Ocean (Chicago, Ill.), March 28, Aug. 6, 1889; Alton Daily Telegraph (Ill.), Aug. 8, 1890; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 1, 1891. On Bryant see Barbara A. Gannon, The Won Cause: Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic (UNC Press, 2011), pp. 22, 68, 70; George W. Bryant Compiled Service Record, http://www.fold3.com/image/263456615; Omaha Daily Bee (Ne.), Oct. 30, 1900; New Orleans Times-Picayune, Sept. 8, 1876; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Aug. 26, 1880; Baltimore Sun, July 15, 1884; Southwestern Christian Advocate, Apr. 23, 1885; Decatur Republican (Ill.), July 14, 16, 1891; Daily Inter Ocean (May 7, 1895); The Appeal (St. Paul. Minn.), Aug. 17, 1901. For Bryant’s references to Cailloux see for example Inter Ocean, Aug. 7, 1891; Saint Paul Globe (Minn.), Aug. 7, 1891. For the association’s plans for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago see Topeka Daily Capital (Ks.), Sept. 3, 1891. On Cailloux and black officers see Stephen J. Ochs, A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006) and James G. Hollandsworth, Jr., Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience during the Civil War (LSU Press, 1998). On later press coverage see, Saint Paul Globe, June 15, 1892; Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 7, Dec. 31, 1892; Brooklyn Citizen, May 16, 1892; Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1892; Washington Bee (D.C.), July 30, 1892; Pittsburgh Press, Aug. 11, 1892; Weekly Bee (Sacramento, Ca.), Sept. 2, 1894. For Bryant’s political rhetoric see Atchison Daily Champion (Ks.), June 9, 1892; North American (Philadelphia), June 9, 1892; Philadelphia Times, Jan. 2, 1893; Colored American (Washington, D.C), Dec. 1, 1900. On the 1893 World’s Fair, see Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn and Ferdinand L. Barnett, The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893).