Over the course of the winter of 1860–61, a cohort of self-described conservatives waged a prolonged campaign to avert civil war in the aftermath of the election of Abraham Lincoln and the subsequent secession of seven Southern states. Among the leaders of this movement for peace was Lincoln’s longtime rival and defeated presidential candidate Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas’s Democratic Party had foundered on the shoals of sectionalism in the 1860 campaign, leading to rival Northern and Southern Democratic tickets and a decisive Republican victory in the electoral college. Nevertheless, the “Little Giant” remained committed to maintaining the Union on the basis of fraternal affection. As he desperately sought to avoid bloodshed, Douglas warned that the Union could never be maintained through “coercion” and castigated his Republican rivals for their antislavery “extremism,” which he blamed for inflaming Southern “Fire Eaters” and leading the country to the brink of disaster. As the nation splintered, Douglas worked tirelessly in the halls of the U.S. Senate to promote compromise measures that might reunite the country and save the Union.

Following the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Douglas and his followers might have plunged into despair and continued to denounce both the Republicans and the secessionists, claiming a position of neutrality in a civil war they had earnestly sought to avoid. Although a minority of Northern Democrats followed this course, the overwhelming majority reacted with indignation to the secessionist attack on the national colors and rallied to the cause of the Union. Without abandoning their identity as Democrats, Douglas and his followers made it clear that their commitment to the government of the Founders would take precedence above all else.

This bipartisan reaction against secession in the North was not guaranteed, and it arose out of a particular political impetus often overlooked by historians. Most recent scholarship has sought to explain the motivation of Union forces by highlighting radical antislavery threads in the antebellum Republican Party. Although these strands certainly existed within the Republican fold, they appear far less significant from a pre-war—or even early war—perspective. The focus on Republican radicalism overlooks the activities of Northern Democrats in the political melee preceding secession and their response to war itself. Although partisanship reemerged as a sharp dividing line in Northern politics during the conflict, many Democrats continued to loyally back the war effort, and some even grudgingly accepted emancipation as a military necessity. Ultimately, we can only explain Union victory and emancipation when we grapple with why so many anti-abolitionist Northerners signed up to fight against their Southern slaveholding countrymen.

In my book, Holding the Political Center in Illinois: Conservatism and Union on the Brink of the Civil War, I argue that Douglas’s Democrats and Lincoln’s Republicans, as well as the Know-Nothings and oldline Whigs, shared a common economic vision for Illinois and the western prairies beyond the Mississippi where their sons and daughters would eventually make their homes. They imagined a society in which free white men would carve out communities while governing themselves under the auspices of the Constitution and the Union. They considered the Constitution “the most sublime institution of human wisdom” and credited the Union with “the fairest scenes of individual and national happiness.” While the rest of the world remained subject to “the shackles of tyranny and oppression,” the United States enjoyed an unprecedented combination of political liberty, constitutional stability, social mobility, and economic opportunity. [1] For all this common ground, Illinois’s partisans nevertheless clashed on a wide range of issues and battled ferociously to claim the political center and the mantle of conservative.

Neither revolutionary nor reactionary, conservatism for Americans of the mid-nineteenth century represented the political center, a middle path that balanced the passion of the moment with the wisdom of the past. In a moment of tremendous social, political, and economic change, it served as a guiding star for many as they sought to balance their hopes for the future with a profound fear that forces beyond their control would destroy it. Throughout this period, political coalitions in Illinois remained fluid. The disruption to Northern politics precipitated by the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 did not neatly reorganize voters. Instead, it initiated a process of realignment that continued through the beginning of the Civil War. The united reaction against secession that propelled Lincoln and Douglas to make common cause in the opening months of the Civil War arose out of an unconditional commitment to the Union that defined the politics of self-identified Illinois conservatives.

Indeed, once word of the fall of Fort Sumter reached Washington, D.C., Douglas made it clear that for all their past differences, he would stand firmly behind Lincoln. The Little Giant insisted that, while he remained “unalterably opposed to the administration on all its political issues,” he would “sustain the President in the exercise of his constitutional functions to preserve the Union, and maintain the government, and defend the Federal Capital.” Rallying energetically to the Union cause, Douglas endorsed a “firm policy and prompt action” by President Lincoln. Writing to a St. Louis editor sympathetic to the Confederacy, he resolutely declared, “I am with my country and for my country, under all circumstances, and in every contingency.” In a meeting with the president shortly before his initial call for volunteers to put down the rebellion, Douglas recommended that Lincoln more than double his request and ask for two hundred thousand men rather than seventy-five thousand. He further suggested that Lincoln immediately strengthen key posts in Virginia, such as Fortress Monroe and Harpers Ferry, in anticipation of a secessionist push to seize these positions. [2] Indeed, until his untimely death on June 3, 1861, Douglas dedicated himself to a vigorous prosecution of the war for Union.

In Douglas’s home state, supporters of the Little Giant rushed to endorse his position. In the capital of Springfield, the Democratic Illinois State Register rallied its readers to the Union cause:

“Whatever may be our party leanings, our party principles, our likes or dislikes, when the contest opens between the country, between the Union, and its foes, and blows are struck, the patriot’s duty is plain—take sides with the ‘stars and stripes.’ As Illinoisans, let us rally to one standard. There is but one standard for good men and true. Let us be there. Through good and through evil report, let us be there—first, last and all the time!” [3]

Echoes of this theme were found in pro-Douglas organs throughout the state, as The Rock Island Argus declared, “The fight is upon us, and it is a fight for our existence, as a government. . . . Let the wrangling about party politics, and the causes of war be forgotten, and let us use every effort now to sustain our government.” [4] The Ottawa Free Trader joined the chorus and insisted that “the people of the States which still adhere to the Union cemented by the blood of our fathers, will be a unit in standing by the Government in defending its possessions and asserting the rightful authority wherever and in what case soever opposed.” [5]

Indeed, Douglas’s correspondence from Illinoisians reveals how determined his supporters were to show that loyal Democrats were as willing as their Republican counterparts to risk life and limb in the nation’s service. Frank B. Smith of Chicago explained to Douglas that it was because of his “Union and Anti Republican proclivities” that he felt compelled to show his “fellow countrymen the depth of [his] attachment to [the] country” by joining the army. [6] Another of Douglas’s supporters in Chicago noted that an overwhelming tide of support for the Union cause had swept the city as men from all backgrounds rushed to enlist: “War Excitement intense, all for fight, party abliterated, all Patriots, & in for the Union, Illinois will tender over 20,000 men.” [7]

William Troxell, of Jo Daviess County, offered an especially rich explanation of his decision to stand by the Union in a letter to Douglas drafted sometime in May:

“It has taken me a long time to make up my mind to fight the people of the south particular the border states some of which have now gone out, but I have come to the conclusion Great as is my friendly feelings for the south my duty as an american citizen compels me to stand by the Government of the United States. I have allways regarded with fraturnal good will but the ties of brotherhood were severed at Sumpter and until they ceas to hated treason—until they substitute the Glorious stars and stripes for the flag recognized by no nation I must consider them enemies not friends, I had ardently hoped the great effort made by you and the venerable son of Kentucky would finaly effect a compromise to allay the storm which I fear will soon sweep from their orbit every slave holding state, but the day of compromise is over we must prepare to sacrifice all for the Government—” [8]

Troxell’s account underlines the significance of the Union in the minds of ordinary white Northern men across the political spectrum. For white Northerners of the mid-nineteenth century, the Union, secured by the blood of their Revolutionary forefathers, represented the safeguard of political liberty, economic prosperity, and social tranquility. For years, Northern moderates had compromised with their Southern slaveholding countrymen with the hope of preserving the republic. Many had ardently supported efforts to conciliate Southerners and restore national tranquility throughout the secession crisis, but they ultimately refused to accept disunion as the price for peace. While partisanship had shaped the political crisis that precipitated secession and remained a potent influence in Northern political life, unconditional Unionism, common to self-identified Northern conservatives of all parties, proved a more powerful force.

Ian T. Iverson is the author of Holding the Political Center in Illinois: Conservatism and Union on the Brink of the Civil War (Kent State University Press, 2024), and he serves as associate editor of the John Dickinson Writings Project at the University of Delaware. A graduate of Princeton University, he holds a PhD in American history from the University of Virginia. His doctoral dissertation won the 2023 Hay-Nicolay Dissertation Prize, awarded by the Abraham Lincoln Association and the Abraham Lincoln Institute for the best dissertation on Lincoln’s legacy.

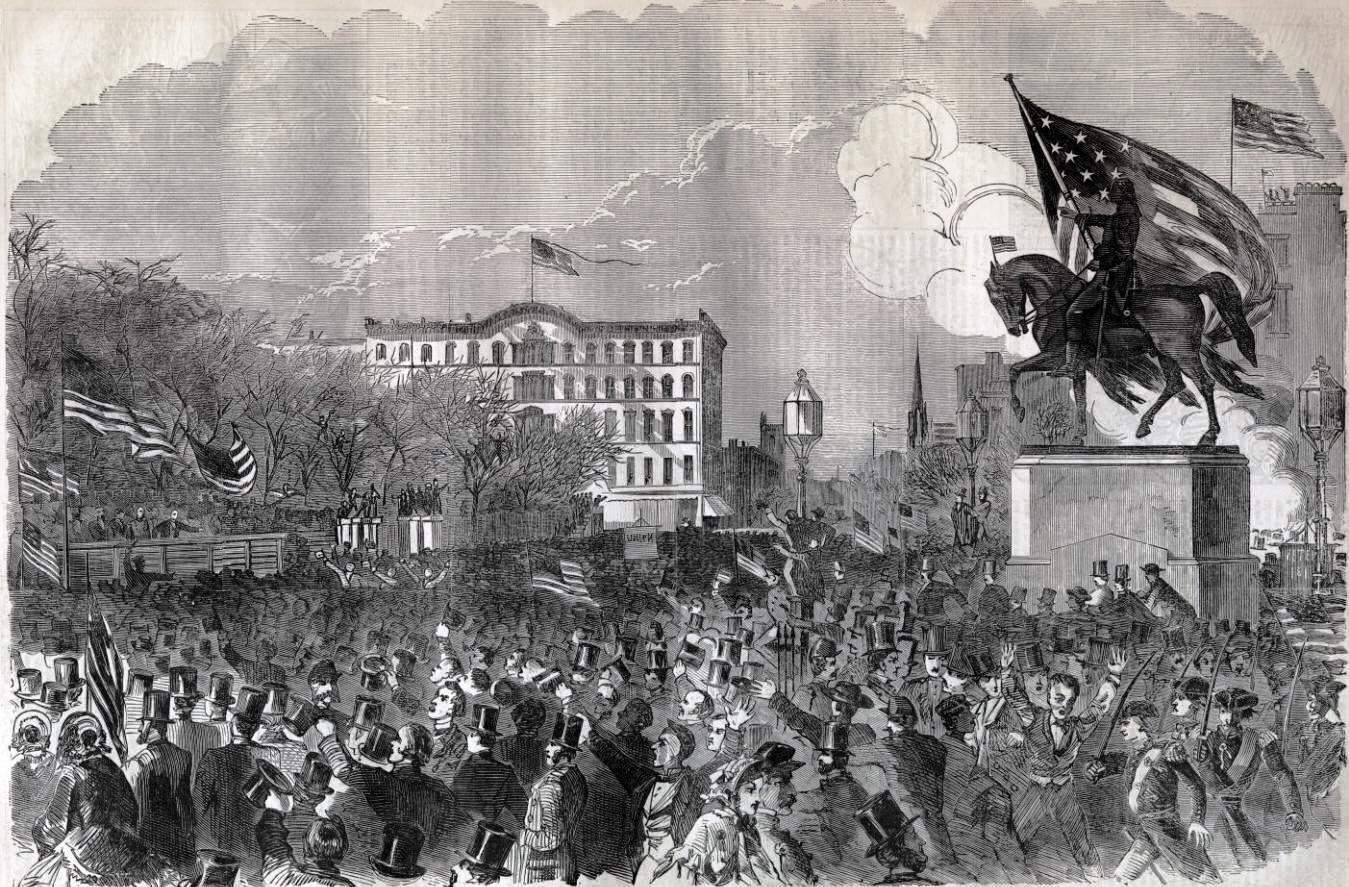

Image: "The Great Meeting in Union Square, New York, to Support the Government, April 20, 1861" Harper's Weekly, May 4, 1861

Notes:

[1] The Ottawa Free Trader, July 28, 1855.

[2] Statement, April 14, 1861, and Stephen A. Douglas to James L. Faucett, April 17, 1861, both in Robert W. Johannsen, ed., The Letters of Stephen A. Douglas (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 509, 510; Robert W. Johannsen, Stephen A. Douglas, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press), 559–60.

[3] Daily Illinois State Register (Springfield), April 16, 1861.

[4] The Rock Island Argus, April 17, 1861.

[5] The Ottawa Free Trader, April 20, 1861.

[6] Frank B. Smith to Stephen A. Douglas, April 16, 1861, Box 40, Folder 19, Stephen A. Douglas Papers, University of Chicago Library.

[7] John A. Thompson to Stephen A. Douglas, April 17, 1861, Box 40, Folder 20, Stephen A. Douglas Papers, University of Chicago Library.

[8] William Troxell to Stephen A. Douglas, May 1861, Box 40, Folder 20, Stephen A. Douglas Papers, University of Chicago Library.