This summer, I was one of five digital research interns at Virginia Humanities, and one of two coming from UVA. I was hired to conduct research for the Descendants Workshop, a part of the Virginia Black Public History Institute and the African-American Cultural Resources Task Force created by the General Assembly. My job was to work with a group of descendants of people enslaved at one of the five sites the project covered: Pharsalia in Nelson County, McChesney Farm in Rockbridge County, Green Hill in Campbell County, Berkeley in Charles City County, and Ampthill Plantation in Cumberland County, which was my descendant group’s site. Over the course of the summer, my role was to research their site and create something to tell their story.

I had the privilege of working under Jobie Hill, a renowned preservation archaeologist most known for her work on preserving slave houses across the United States, and Justin Reid, Virginia Humanities’ Community Initiatives Coordinator and a descendant of Ampthill’s enslaved community. I’d also be remiss not to mention the amazing work of the other interns on the Descendants Workshop with me, especially my fellow UVA student Tyler Busch. His work on the resiliency of enslaved Black women at Pharsalia and the connection to descendant identity as mothers was incredible, and being able to work with such a talented group of fellow students was such an honor.

We met three days a week to discuss our progress as well as issues facing the field of Black public history. Black historical sites are continually disrespected and erased from the public record. It’s a cyclical process—slaveholders sought to marginalize and dehumanize African Americans, and they often prohibited them from learning to read and write. As a result, enslaved people left fewer written records, and communities preserved fewer Black historical sites. For decades, many white historians used this apparent lack of evidence to deny African Americans’ historical importance. My research experience really taught me the importance of looking at very small details, things like creative design work in masonry, or certain types of plants meant to signal to others they were in a graveyard as expressions of Black historical agency and evidence of the lives they lived. This project also taught me the importance of familial oral history as a guiding point for exploring the past, and the necessity of communal elders to public and personal history.

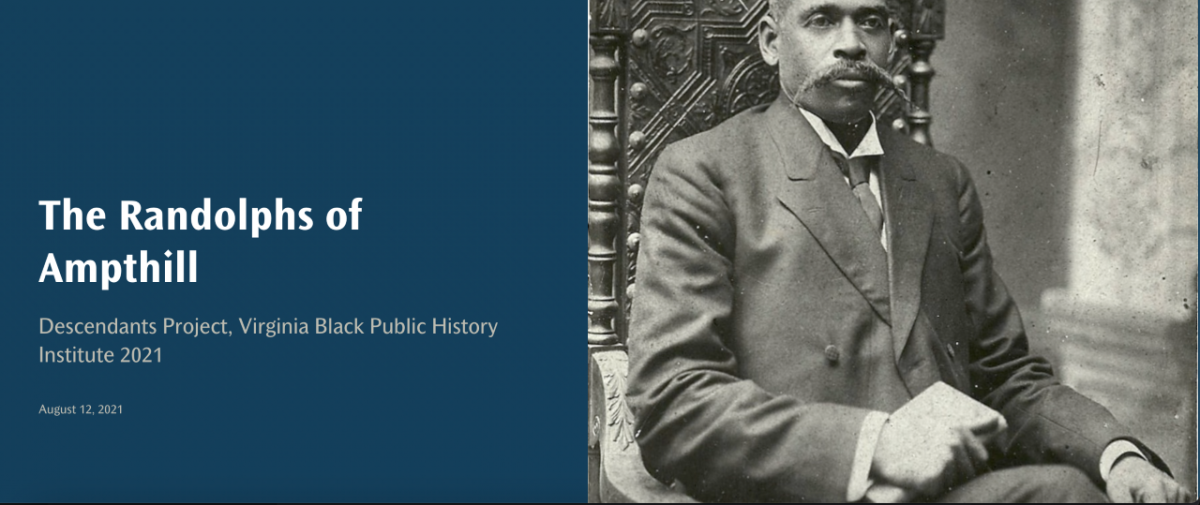

My group ended up making an ArcGIS StoryMap about their experience researching, visiting, and reflecting on Ampthill, centering around Reverend Jacob Randolph, their common ancestor. My job was to make the StoryMap from the photos, audio, and narratives they provided me, supplementing it with my own research. The first part of the summer was focused primarily on research, while the second part focused on site visits and narrative creation. Throughout the summer, I learned how to use ArcGIS and communicate narratives through its StoryMap feature. I gained a lot of digital research experience with UVA’s databases and archives that I wasn’t super familiar with, such as AncestryLibrary.

The Virginia Black Public History Institute was very gracious to invite me to take part in this internship, and I’m very grateful for the opportunity and for all I’ve learned over the summer. That being said, the mission of the Descendants Workshop, and VBPHI as a whole, was very much centered around Black scholarship and historical agency. As a white student at UVA, there are very few spaces that don’t explicitly center that part of my identity, but this was one of them. Everyone in the group was very kind and accommodating, but being the only non-Black person on the project made me feel like a Black intern would have been a better fit for this specific position. Even though I wasn’t an ideal fit for the project, it was a very good opportunity for self-reflection about my own experience with genealogy and perception of history. Getting to study public history in a way that centered Black contribution and agency changed the way I look at history now, because a lot of the white historical myths we talked about were things I’ve heard from people around me. The most important thing I got out of this internship was a much deeper understanding of how much white public memory minimizes slavery, and the ways in which that happens.

The methods themselves also took me out of my comfort zone, which helped me really grow as a historian and researcher. I’m most familiar with 19th-century political history, so focusing on genealogy was very different and a lot more granular than what I was used to doing. Looking at how specific people and families navigated life outside of the political sphere was really interesting, and it gave me a better understanding of the ways in which people entrenched slavery into every part of antebellum society. I also learned a lot about Virginia history. I got to really see how a few families—in my case the Randolphs and Harrisons—held so much sway, and I learned what that means for their Black descendants. Walking around UVA now and seeing just how many names of slaveholder families I recognize from my research is a disheartening reminder of where exactly this university’s wealth comes from and just how far we have to go to move towards equity.

I very quickly realized in my research that my own family’s experiences with genealogy, traced by my great-grandparents, was informed by the early 20th-century nativist movement. This movement pushed genealogy as a way of finding proof that your ancestors were Anglo-Saxon and had been present in the United States for a long time, and it emphasized connections to famous early Americans. My ancestors also moved around a lot as a result of their participation in settler-colonialism, so the idea of being a descendant of a specific place was also new to me. Black genealogy is a lot more about reclamation and agency, and getting the opportunity to research on that front was a valuable learning experience. The institution of slavery deliberately attempted to erode ethnic identity and familial ties, so finding out who you are and where you’re from is an act of reclamation, defiance, and the beginning of healing from generational trauma. Because of the centuries of deliberate erasure, genealogy is much harder, and running into the many ways Black people were marginalized out of the historical record every day during research made me really appreciate the importance of this project. Knowing who your ancestors were is a privilege I had not fully appreciated.

The closest I ended up coming to the Civil War was looking into “Burnt-Out Counties,” or the places whose municipal records were almost completely destroyed during the Civil War, either by the Union Army or during the burning of Richmond. I saw firsthand how enslaved people often only showed up as nameless entries in tax records and other municipal documents, which were often destroyed or intentionally misleading. There’s so much work for historians to do to even stop continuing this systemic erasure, let alone to rectify it.

This internship was primarily remote, but one of the highlights was that we got to go on site visits to the plantations we were studying. I got to go to Ampthill, and since I was in town, I tagged along on the Berkeley and Pharsalia site visits, as well. The site visits, especially because of the guidance and commentary from Jobie Hill, also made me think a lot more about architecture, and how plantation construction itself belies violence. Seeing Ampthill in person was very interesting, as it was one of the first times I’ve really gotten to go out in the field and see what I’m studying. Going with descendants and watching as they both processed and spiritually reclaimed the sites their ancestors were enslaved at made the connection between physical place and history feel very strong.

All of the plantations were a study in how white public memory and preservation erases enslaved people. Berkeley was purchased by a different family and preserved as a sort of Colonial-Williamsburg-esque “museum,” but a lot of the preservation was incorrect. Its staff members described all external living spaces as “guest houses,” claimed to not know what the tunnel between the kitchen and the cellar of the mansion had been used for, and employed the narrative that white Scottish indentured servants were also enslaved in the same way on-site. Pharsalia gets the money to do preservation work from hosting weddings, and a lot of the stories we heard from the current owners (white descendants) centered on how enslaved caretakers were treated like family. We talked a lot during site visits about the necessity for white descendant property owners to be willing to expand their understanding of their own properties and to listen to Black descendant groups.

As for Ampthill, almost all of its history focuses on its connection to Thomas Jefferson, who designed the plans for the brick part of the house because his cousin Randolph Harrison owned the property. Today, Ampthill uses language like “brick outbuilding” and “tenant house,” and it incorrectly claims that buildings were constructed after the Civil War. These phrases and assertions all exclude enslaved people from the property’s history. The Descendants Workshop works to decenter that architectural history, focusing on the enslaved people who actually designed and built everything on the property. It was eye-opening facing the reality that no white historian had ever done that for this site before and realizing that it was up to Black descendants to tell the historical truth.

Overall, the genealogical research, site visits, and many important conversations about the future of Black public history and descendant work helped me step out of my comfort zone as a historian and researcher. I gained digital research and software experience, as well as a much more complete perspective on Black history and public memory that I’ll definitely carry forward into my future work.

Images: (1) One of the three slave houses still standing at Pharsalia Plantation; (2) Introductory page of the ArcGIS StoryMap that Elise and her group put together