On July 31, 1866, Susan Jackson, a freedwoman living in Virginia’s Albemarle County, stood before William Tidball, Charlottesville’s agent for the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands. The transition out of enslavement had been difficult for Jackson. In ill health, penniless, and virtually alone, she relied on an allotment of Bureau rations to keep body and soul together.[1] But it was not her physical state that brought her to Charlottesville that day. More than a year after slavery’s collapse, Jackson had come to find the three children whom she had lost a decade earlier to the domestic slave trade. Jackson’s enslaver (whom she did not name in her complaint) had sold Fielding (then a boy of about twelve) to a Richmond slave trading firm and Priscilla (about sixteen) and Anderson (age unknown) to a Petersburg-based dealer.[2] These men had, in turn, carried the children to points unknown. Jackson laid what little information she held about them before Tidball and, through the Bureau, launched a multi-state quest for her lost family. Her efforts to find her children illustrate not only the central place family held in freedpeople’s conceptions of liberty, but also the Bureau’s methods for tracing families through the flotsam and jetsam of enslavement—and its multivalent motivations for engaging in this task.

The scraps of information to which Susan Jackson clung reflected slave commerce’s shattering impact on thousands of enslaved Virginian families. In the half century before the war, children like Fielding, Anderson, and Priscilla stood nearly a one in three chance of being sold away from their families; by the time Jackson sought them out, Virginians had funneled the equivalent of the state’s entire 1860 black population to the Cotton South, mostly via the slave trade.[3] Enslaved children internalized the possibility of sale at an early age, sometimes with traumatic effects, but cognizance of the slave trade’s omnipresence scarcely diminished the deep bonds they shared with their parents.[4] And while some families treated sale as a de facto death, others worked tirelessly to obtain information regarding those whom they had lost in anticipation of a day when they might put this knowledge to use.[5]

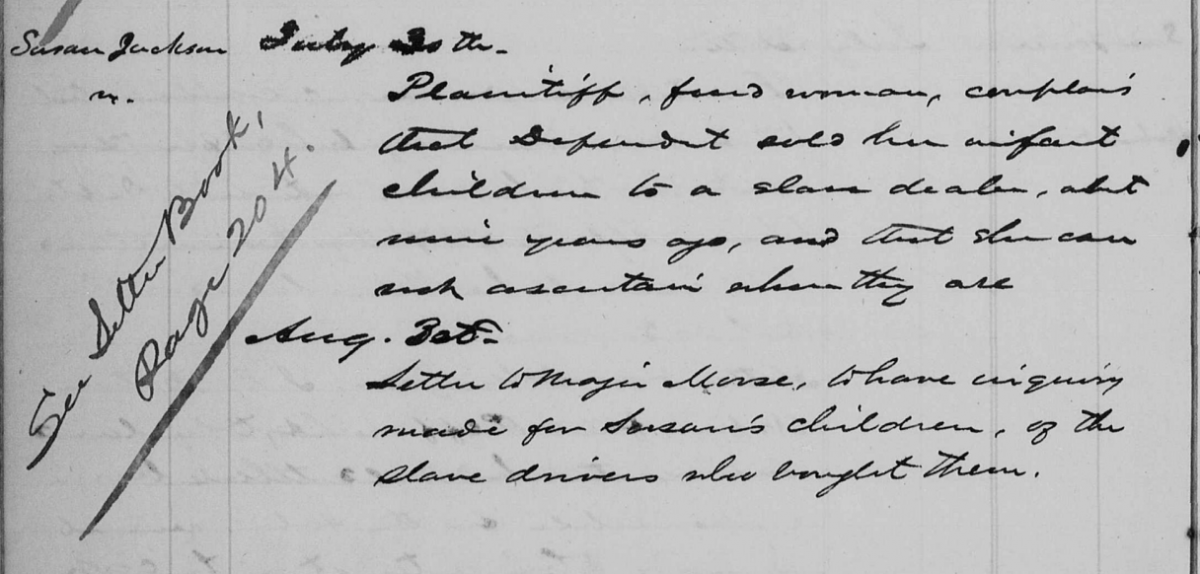

For Jackson, that day came in the summer of 1866. How she learned what she conveyed to Tidball remains opaque, but she named the slave dealers who had acquired her children as well as one possible purchaser. Eberson & Smith, a Richmond slave trading partnership, had bought Fielding and sold him (Jackson believed) to a man named Glover. Petersburg’s Lew Jones had purchased Anderson and Priscilla. Of their locations, she had heard only a rumor. A South Carolina woman had told Jackson that in a Charleston hotel she had met a young woman named Priscilla who appeared to be the same age as her lost daughter.[6] Though a relatively thin reed, Jackson nevertheless had more to go on about her children than did most people in similar situations.[7] Information, however, was no guarantee of results; other freedpeople possessing similar details regularly came away from efforts to trace family members empty handed.

We do not know why Jackson waited more than a year after the Civil War to seek the Bureau’s aid. Perhaps she had only recently heard of Priscilla’s possible location. Perhaps deteriorating circumstances forced her to make a desperate and painful effort. Perhaps a neighbor encouraged her to come in, someone like Simon Fleming, who filed the preceding complaint also in search of lost children. Whatever her reasons, Jackson turned to an agency both uniquely capable of such a mission and often ambivalent about pursuing it. Many Bureau agents saw the reconstruction of black families as a tangential (and often irritating) aspect of their work, preferring to focus on facilitating enslaved people’s conversion to a free labor economy. Nevertheless, as they had during the war, freedpeople could sometimes force government agents to adapt to their needs. As one officer put it, newly freed “mothers, once fully assured that the power of slavery was gone, were known to put forth almost superhuman efforts to regain their children.”[8] While freedpeople also used their own networks to pursue family members, the Bureau’s region-wide network officials offered a powerful tool for tracing them—when the agency chose to exert itself.[9]

Fortunately for Jackson, Tidball proved willing and able to aid her in her quest. After dutifully noting her inquiry in the county’s Register of Complaints, he forwarded the details up the Bureau hierarchy. However he may have felt about Jackson’s cause personally, her circumstances merited an active response, for finding Jackson’s family would right a decade-old wrong while abetting the Bureau’s broader efforts to mitigate slavery’s economic aftershocks. Jackson was elderly (how old, as was so often the case for the enslaved, it is impossible to say). Her physical maladies were myriad, including being “greatly afflicted, with dropsy and otherwise,” which rendered her “much of the time unable to do anything for her own support.”[10] Without a family to care for her, she had become the Bureau’s direct responsibility.[11] She was thus a living embodiment of its deep fear of black dependence upon governmental support. “The aim of Bureau relief policy almost from the start,” one scholar notes, “was to discontinue relief to the freedpeople as quickly as possible.” In some cases, this meant removing children whom it deemed parents could not support; in Jackson’s case, however, it dictated in favor of finding hers.[12] “If her children can be found,” Tidball argued, “it will not only be a great comfort to her, but a relief to the Bureau.”[13] Finding Fielding, Anderson, or Priscilla, in other words, would not only offer Jackson emotional catharsis, but would advance the Bureau’s broader quest against dependence.

The Bureau’s efforts to find Fielding uncovered limitations that surfaced all too frequently in searches for lost family members. Armed with the information Jackson had provided, local agents in Richmond sought out Eberson & Smith, but to no avail. Both had died in the intervening years and any knowledge or documentation of Fielding’s location perished with them.[14] If the Bureau followed its standard practices, its agents made announcements in the local churches and placed inquiries in spaces that formerly enslaved people frequented, but in this case with no results.[15] Tragically, Fielding may have been living only a few counties away; even as Bureau agents searched for him in Richmond, a Fielding Jackson of about the right age appeared in a Bureau-sponsored contract in Rappahannock County—and remained there per the 1870 census.[16]

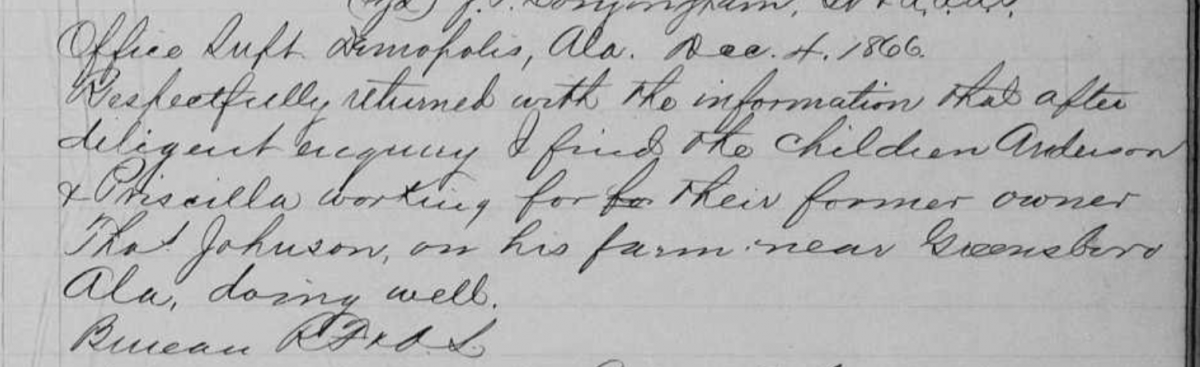

The search for Priscilla and Anderson, however, proved more fruitful. Tidball’s message went first to Petersburg, where Lew Jones had dealt in humanity from an office on Bollingbrook Street. He had vacated that space, but the Bureau’s correspondents traced him to Nottoway County. Local agents found Jones not only alive, but willing to cooperate, a trait rare in ex-slave traders. He reported that he had kept Jackson’s children for several years, but that during the war he had carried them to Greensboro, Alabama, and sold them there. While he could not recall to whom he had sold them, Bureau operatives now had a thread on which they could pull.[17] Jackson’s inquiry flew up the chain of command to the Virginia Assistant Commissioner’s office, from which it leapfrogged to the national office, then to Montgomery and the Assistant Commissioner for Alabama, who handed it off to the Demopolis branch office.[18] Agents there soon found Priscilla and Anderson working for Thomas Johnson, the man who had bought them during the Civil War.[19]

We can only imagine how Susan Jackson responded upon receiving this happy news. We cannot know whether she had waited with anticipation or resignation, or how she had reacted to news of the failed search for Fielding (if she learned of it at all). Surely she rejoiced that two of her children were not only alive, but together and “doing well” in Alabama. How she felt about Priscilla’s marriage, or whether she learned then of the daughter Priscilla had named for her we cannot know.[20] But in news that likely gladdened the Bureau as well as Susan, Priscilla believed that she and her family could offer Jackson the support she so badly needed. Assured of this, Bureau officials quickly approved her request for transportation to Greensboro, Alabama—with which she disappeared from the written record. We can only hope that she lived the remainder of her life happily with her children and granddaughter.[21]

An array of Freedmen’s Bureau officials had helped Susan Jackson become one of a fortunate group of freedpeople who successfully traced relatives stolen from them by the domestic slave trade. Simon Fleming’s experience underscores the precious and contingent nature of this success. Simon Fleming had also come to Charlottesville on July 31, also seeking three children sold away from him; given these similarities, it is hard to imagine that the two did not commiserate.[22] Earl Marshall, Fleming’s enslaver, had named the slave trader involved; Hector Davis, a notorious Richmond dealer, had sold off all three children: Maria (age nineteen) in 1857, James (seventeen) and Mary Frances (fourteen) in 1859.[23]

Fleming’s subsequent experience shows that Susan Jackson and the Bureau had been very fortunate in finding Lew Jones alive and forthcoming.[24] Fleming’s inquiry failed on both counts. Hector Davis had died in 1863, and his accounts and business records had passed into the hands of his former clerk, R. D. James. When Bureau agents requested any information that James could provide, he turned them down flat. Had they been able to see Davis’s books, Bureau officials could have learned that J. Wilson (likely the New Orleans slave trader J. M. Wilson) purchased Maria on July 7, 1857; A. W. Pearce purchased Mary Frances on November 17, 1858, and three days later William S. Deupree—a slave trader operating between Richmond and Alabama— purchased James, separating the siblings (in all likelihood) forever.[25] The Bureau might have been able to make something of this information; in denying it to them, James robbed the Flemings of the barest chance at a reunion and ensured that the work domestic slave dealers had begun in the antebellum period remained intact in the aftermath of emancipation.

Jackson’s successful search for her children illuminates the possibilities inherent in the freedom that the Civil War brought through reconstructed families and a chance for self-sufficiency—as well as the Federal government’s desire to promote these values, especially when they coincided. Her experience represents, in many ways, the best of what the Freedmen’s Bureau could accomplish. Simon Fleming’s experiences bring that reality into stark relief and demonstrates the contingent nature of postwar freedom. Armed with an almost identical set of facts and a seemingly equal chance at reunion, Fleming remained deprived of his children. Freedom brought opportunity, but no guarantees, even when the Freedmen’s Bureau proved willing to put forth its power. The successes and failures of these Albemarle County freedpeople thus demonstrate the potential inscribed within emancipation, but also the powerful and generational legacies slavery and the domestic slave trade left in African American life.

Robert Colby teaches American Studies at Christopher Newport University. His research on the wartime slave trade has received multiple awards, including the Society of American Historians' Allan Nevins Prize and Society of Civil War Historians' Anne J. Bailey Dissertation Prize.

Mazie Clark is a junior at Christopher Newport University. Besides working with Dr. Colby as part of CNU's Summer Scholar Program, she is a history major, a member of Christopher Newport's marching band, and a thrower for the track & field team.

Images: (1) “Glimpses at the Freedmen's Bureau. Issuing rations to the old and sick / from a sketch by our special artist, Jas. E. Taylor,” Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, September 22, 1866 (courtesy Library of Congress); (2) Susan Jackson v. Unknown, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co., Register of Complaints, Jun 1866-May 1867, and (3) Office of the Superintendent, Demopolis, Alabama, December 4, 1866, VFBFOR, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, June 1866-Dec 1868 (both courtesy National Archives and Records Administration);

Notes:

[1] William Tidball to W.R. Morse, March 16, 1867, Virginia Freedmen's Bureau Field Office Records, 1865-1872 (VFBFOR), Charlottesville, Albemarle County Assistant Subassistant Commissioner (ASC), Roll 65, Letters Sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, image 290 of 371, NARA M1913. All Freedmen’s Bureau records obtained via FamilySearch.org. All are NARA M1913, unless stated otherwise. Anna Greener to William Lewis Tidball, October 24, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 66, Letters Received, Mar 1866-Jan 1868, Image 326 of 1119.

[2] Fielding Jackson, 1870 U.S. Census, Rappahannock County, Virginia; Priscilla Mosely, 1870 U.S. Census, Hall County, Alabama [Database On-Line] Provo, UT USA Ancestry.com.

[3] Michael Tadman, Speculators and Slaves: Masters, Traders, and Slaves in the Old South (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 12, 45.

[4] Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017), 33-91; Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 28-39.

[5] Williams, Help Me to Find My People, 120-138.

[6] Tidball to Morse, August 3, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 65, Letters sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, image 107 of 371.

[7] For an example, see the experience of Jane Henderson, whose enslaver had brought her from Charlotte, NC to Albemarle County during the war. Tidball to Morse, October 26, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 65, Letters Sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, image 181 of 371.

[8] Mary Farmer-Kaiser, Freedwomen and the Freedmen’s Bureau: Race, Gender, and Public Policy in the Age of Emancipation (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 97; Williams, Help Me To Find My People, 145-147.

[9] For examples, see “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery,” https://informationwanted.org.

[10] Tidball to W.R.Morse, March 16, 1867, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle County ASC, Roll 65, Letters Sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, image 290 of 371.

[11] Greener to Tidball, October 24, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 66, Letters Received, Mar 1866-Jan 1868, image 326 of 1119.

[12] Mary J. Farmer, “‘Because They Are Women’: Gender and the Virginia Freedmen’s Bureau’s ‘War on Dependency’” in Paul A. Cimbala and Randall M. Miller, eds., The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction: Reconsiderations (New York: Fordham University Press, 1999), 161-192. Quote on p. 168.

[13] Tidball to Morse, August 3, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 65, Letters sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, image 107 of 371.

[14] Registered Letter, August 23, 1866, VFBFOR, Gordonsville, Superintendent, 4th district, Roll 92, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, Jun 1866-Dec 1868, image 41 of 446.

[15] See, for example, Endorsement, Benjamin C. Cook to H.S. Merrill, April 19, 1866, VFBFOR, Office of the Subdistrict of Richmond, Richmond Subassistant Commissioner, Roll 164, Endorsements Sent and Received, Vol. 1-3, April 1865-Dec. 1868, image 162 of 398.

[16] Fielding Jackson, 1870 U.S. Census, Rappahannock County, Virginia, [Database On-Line] Provo, UT USA Ancestry.com; Article of Agreement, Hamilton Fletcher and Bob Jackson, April 16, 1866, VFBFOR, Little Washington, Roll 103, Letters and Orders Received, Letters Sent, and Contracts, 1865-1866, Image 439 of 506.

[17] D.G. Connolly to J.R. Stone, October 9, 1866, VFBFOR, Gordonsville, Sup. 4th Dist., Roll 92, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, Jun 1866-Dec 1868, image 113 of 446.

[18] Various Endorsements, VFBFOR, Gordonsville, Sup., 4th Dist., Roll 92, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, June 1866-Dec. 1868, Image 113 of 446.

[19] Office of the Superintendent, Demopolis, Alabama, December 4, 1866, VFBFOR, Gordonsville, Sup., 4th Dist., Roll 92, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, June 1866-Dec. 1868, Image 113 of 446.

[20] Office of the Superintendent, Demopolis, Alabama, December 4, 1866, VFBFOR, Gordonsville, Sup. 4th Dist., Roll 92, Registers of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent, Vol. 1-3, June 1866-Dec 1868, Image 113 of 446.

[21] It seems likely that Anderson lived in Russell County, Alabama, per an 1866 state census. “Anderson Jackson,” Alabama State Census, 1866, Russell County [Database On-Line] Provo, UT USA Ancestry.com; Tidball to Morse, March 16, 1867, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 65, Letters Sent, Vol. 1-3, Nov 1865-Jun 1867, Image 290 of 371. Susan Jackson does not appear in the household under the 1870 census; it seems likely, given her age and infirmity, that she had passed away in the intervening years.

[22] Simon Fleming v. Earl Marshall, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 67, Register of complaints, Jun 1866-May 1867, Image 69 of 101.

[23] Tidball to Morse, August 16, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 66, Letters received, Mar 1866-Jan 1868, image 243 of 1119.

[24] Benjamin C. Cook to Paul R. Hambrick, September 26, 1867, VFBFOR, Richmond Assistant Subassistant Commissioner, Roll 171, Letters Received, Jan. 1866-Dec. 1868, Image 583 of 919. Jones offered similar aid on at least one occasion. See D.J. Connolly to J.R. Stone, October 11, 1867, VFBFOR, Richmond Assistant Subassistant Commissioner, Roll 170, Register of Letters Received and Endorsements Sent and Received, Dec. 1866-Dec. 1868, Image 170 of 231.

[25] Tidball to Morse, August 16, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 66, Letters Received, Mar. 1866-Jan. 1868, Image 243 of 1119; Endorsement, Benjamin C. Cook, August 27, 1866, VFBFOR, Charlottesville, Albemarle Co. ASC, Roll 66, Letters Received, Mar. 1866-Jan. 1868, Image 241 of 1119; Entries for July 7, 1857; November 17, 1858; November 20, 1858, Hector Davis Daybooks, 1867-1865, Chicago History Museum; “Negroes for Sale,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, January 16, 1857; “Dissolution,” Richmond Daily Dispatch, June 4, 1858.