George Gordon Meade and the Cropsey Affair

by Jennifer M. Murray | | Tuesday, December 11, 2018 - 15:33

Visitors to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, will find no shortage of tourist and trinket shops in town, each selling a variety of Civil War souvenirs, memorabilia, and paraphernalia. The battle, its generals, and its leaders have been commercialized and commodified, their images placed on innumerable products, ranging from t-shirts to bobble-heads to decorative art. Recently, one tourist store offered interested buyers a framed Gettysburg collage. Five musket balls line the frame, with an artistic rendition of Union and Confederate soldiers in hand-to-hand combat in the center, flanked by photos of the two commanding generals at the battle of Gettysburg: Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant.

This is more than an anecdote.

More than 150 years since the battle, visitors to Gettysburg commonly demonstrate little knowledge about, or enthusiasm for, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. To be sure, the reputation and prestige of the “Victor of Gettysburg” had fallen mightily since early July 1863. Elated by victory at Gettysburg, northerners lavished praise upon the general. One newspaper even championed Meade as a presidential candidate in 1864.[1] The arrival of Grant to the eastern theater in the spring of 1864, and his decision to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac served to overshadow Meade’s role in the war’s final years. Yet, factors other than Grant’s arrival to Virginia explain Meade’s diminishing legacy. Indeed, without the benefit of political patrons and lacking his own political acumen, Meade slavishly executed orders and believed that his commitment to duty would be sufficient to solidify his legacy.

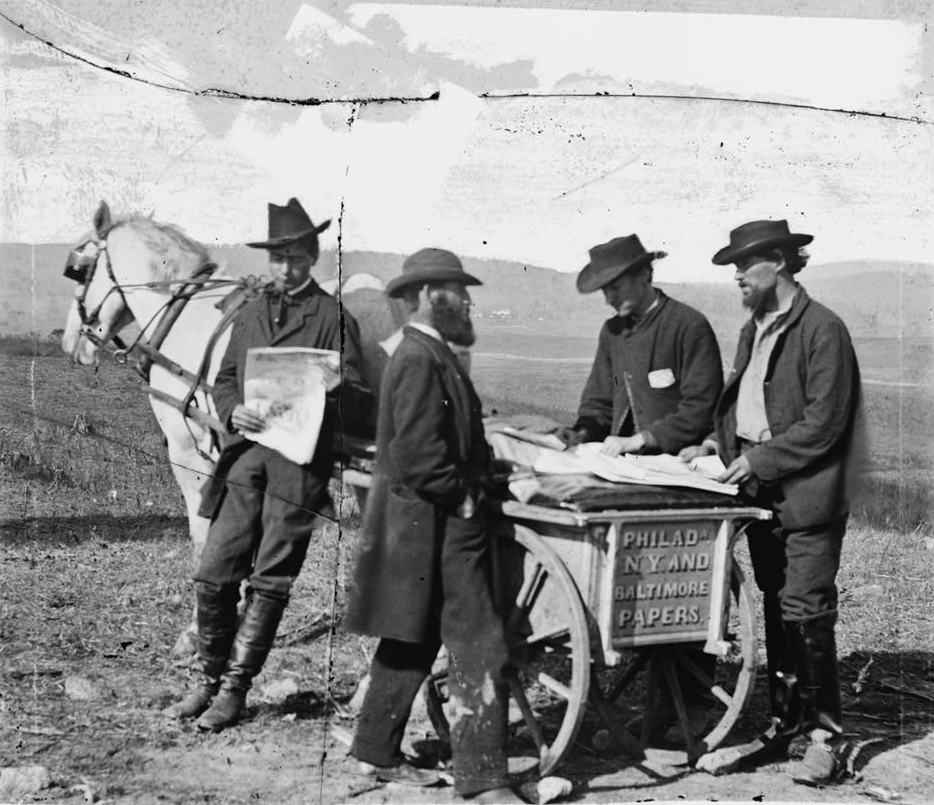

By the summer of 1864, however, Meade became increasingly sensitive to his reputation, particularly the way in which the northern press portrayed his leadership and his role in the Virginia campaigns. More than 3,000 newspapers, including dailies and small-town weeklies, eagerly reported on the nation’s most defining event. Hundreds of war correspondents flocked to battlefields, camps, and campaigned with the armies to get first-hand reports of the war’s operations and personalities. Meade’s concern was more than egotism. Indeed, the press chronicled the war from the front lines, while serving as the primary influence in shaping public opinion. Consequently, when one war correspondent published an article questioning Meade’s leadership in the Wilderness, Meade retaliated. The general’s reaction to the incident, the Cropsey Affair as it would be known, sullied Meade’s reputation with the northern press and in turn irrevocably damaged the general’s reputation.

On June 2, 1864, the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article by Edward Cropsey, a correspondent, on the army’s operations, including the fighting in the Wilderness. Cropsey praised Meade’s leadership, indicating that the Philadelphian remained firmly in command of the army, executing the details of General Ulysses Grant’s strategic plans. Yet, in the final paragraph, Cropsey intimated that the general had favored a turn north across the Rapidan. Indeed, Cropsey wrote, only Grant’s “presence saved the army, and the nation too,” and, as Cropsey reported, Grant proceeded to direct the Federal army toward Richmond.[2]

Five days later, thumbing through his hometown newspaper, Meade read the article.

Meade’s irascible temper was no secret throughout the army; without hesitation, he sought a resolution to Cropsey’s falsehoods. On June 7, Meade ordered Cropsey’s arrest. In his order, perhaps consciously, he spelled the correspondent’s name “Crapsey.”[3] When Cropsey arrived at Meade’s tent, the general demanded an explanation. Cropsey replied that Meade’s intent to withdrawal across the Rapidan had been the “talk of the camp.” The general retorted that such accusation was a “base and wicked lie” and resolved to make an example of Cropsey so as to “deter others from committing like offenses.”[4] As punishment, Cropsey was mounted backward on the “sorriest looking mule to be found,” bearing a placard reading “Libeler of the Press,” and paraded through camp.[5] One Union soldier observing the scene remembered that Cropsey was “howled at.”[6] Meade then banned Cropsey from the army and declared that he would punish correspondents who “circulate falsehood.”[7]

Undeniably, Meade’s handling of Cropsey damaged his standing with the press. Sylvanus Cadwallader, a New York Herald correspondent, later noted that “every newspaper correspondent” in Meade’s army agreed to “ignore Gen. Meade in every possible way and manner.” Thereafter, as the Army of the Potomac maneuvered closer to Richmond, press coverage focused on Grant and, as much as possible, avoided credit to Meade. The censure continued until late October 1864 when Cadwallader instructed Herald reporters to give Meade “fair treatment.” Meade later admitted to Cadwallader that while Cropsey deserved punishment for his falsehoods, his treatment of the correspondent had been a mistake.[8]

News of the Cropsey incident arrived in Washington. Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, who was traveling with the army, telegrammed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that Meade was “very much troubled” at the Inquirer’s article. Stanton replied that he and President Lincoln retained “perfect confidence” in Meade.[9] While this reassured Meade, the general spent the duration of the war largely removed from the paper’s headlines, and increasingly relegated to a secondary role in the newspapers, and thus, the minds of the northern public.

War correspondents exert significant influence on the public’s perception of war and, in turn, its leaders. “Is it not heartsickening to think that one’s reputation depends on such a lot of scum,” questioned Col. James C. Biddle of Meade’s staff.[10] In fact, Union generals’ relations with the press varied. Some, like Grant, found it advantageous to work with the journalists, while others found them a nuisance. During the Chickasaw Bayou Campaign, Maj. Gen. William Sherman ordered Thomas Knox of the New York Herald court martialed for being a spy.[11] Back in Virginia, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside accused New York Times correspondent William Swinton of libel for his article on Burnside’s 9th Corps and cited Meade’s treatment of Cropsey as a precedent for banning Swinton from the army.[12]

The Civil War’s culminating moment came at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. While Grant accepted Lee’s surrender, Meade and his staff awaited the news from their camp nearly four miles away. At Appomattox, a moment forever enshrined in multiple paintings and sketches, Meade was absent from view. Indeed, in the days following the surrender at Appomattox, a time for celebration, Meade continued to fume about the press. “I don’t want to see any more, for they are full of falsehood and of undue and exaggerated praise,” he bemoaned. Aware of his waning reputation among those credited for Union victory, Meade maintained the press ignored his contributions and recoiled as Grant, Sherman, and Philip Sheridan received the adulation of a grateful nation.

George Gordon Meade commanded the Army of the Potomac longer than any other Union general. His contempt for the press and their depiction of his leadership did not dissipate in the postwar years. Meade recognized the influence that newspapers had on shaping public opinion, and indeed in shaping generals’ legacies. Still, the general continued to serve his nation until his death in 1872. “I don’t believe the truth will ever be known,” Meade predicted, “and I have a great contempt for History.”[13] Indeed, he remains relatively obscured in national consciousness and forgotten in the souvenir collages sold in Gettysburg tourist shops.

Jennifer M. Murray is a teaching assistant professor at Oklahoma State University, with a specialization in U.S. Military History and the Civil War. She is the author of On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013 (published in 2014) and is currently writing a biography of George Gordon Meade, tentatively titled Meade at War. Murray also worked as a seasonal interpretive ranger at Gettysburg National Military Park for nine summers.

Images: (1) General George Gordon Meade, (2) Group of Civil War Newspaper Correspondents (courtesy Library of Congress).

Notes:

1. “For President in 1864, Major General George Gordon Meade!” The News (Newport, VT), July 15, 1863. Vol. 35 (Collection 410), George G. Meade Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [hereinafter cited as HSP]. For additional reading on Civil War and the press see: Risley Ford, Civil War Journalism (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2012); David Sachsman, ed. Words at War: The Civil War and American Journalism (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2008).

2. “Meade’s Position,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 2, 1864.

3. George Gordon Meade, Order, June 7, 1864. United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 vols., in 128 parts (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), vol. 36, part 3, 670 [all notes hereinafter cited as OR with corresponding volume and page number].

4. George Gordon Meade to Margaretta Meade, June 9, 1864, HSP [correspondence hereinafter cited as GGM to MM, HSP]. Meade received Grant’s approval for the punishment. Grant indicated that he knew Cropsey to be a reputable individual, but approved Meade’s plan.

5. GGM to MM, June 9, 1864 (HSP); Sylvanus Cadwallader, Three Years With Grant, ed. Benjamin P. Thomas (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 206-207; Marsean Rudolph Patrick, Inside Lincoln’s Army: The Diary of Marsena Rudolph Patrick, Provost Marshal General, Army of the Potomac, ed. David S. Sparks (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company, 1964), 381.

6. Frank Wilkeson, Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac (New York: Putnam & Sons, 1887), 146.

7. Meade, Order. OR, vol. 36, part 3, 670.

8. Cadwallader, Three Years With Grant, 208-209; 256-257.

9. Charles Dana to Edwin Stanton, June 9, 1864. OR, vol. 36, part 1, 94; Edwin Stanton to Charles Dana, June 10, 1864. OR, vol. 36, part 3, 722; GGM to MM, July 12, 1864 (HSP).

10. James C. Biddle to Gertrude, May 16, 1864. Folder 11, Box 1, (Collection 1881), James Cornell Biddle Letters, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

11. John F. Marszalek, Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order (New York: Free Press, 1993), 211-213.

12. Ambrose Burnside to George Meade, June 11, 1864. OR, vol. 36, part 3, 751.

13. GGM to MM, April 10, 1865; GGM to MM, April 12, 1865, HSP.