Bittersweet: Black Virginians in Blue at the Battle of Honey Hill and Beyond

by Matt H. Wallace | | Tuesday, December 4, 2018 - 00:00

After Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman took Atlanta in the fall of 1864, the Union army commenced Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea.” As an auxiliary effort to his main campaign, Sherman ordered an expedition up the Broad River in South Carolina. Sherman hoped to either cut the railroad between Charleston and Savannah in half, trapping the rebels in Savannah, or spread a weakened rebel force across the state. The resulting encounter between the Union and rebel armies resulted in a Union defeat at the battle of Honey Hill. Of the thousands of black men belonging to the several regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT) at the battle, eleven of them were born in Albemarle County, Virginia. Of those eleven, five illustrate the common struggles of free African Americans living in the North and South before and after the war. Decades after their service, the war’s impact on their well-being continued to affect their ability to provide for themselves and their families, forcing them to seek government aid to survive. Those five were brothers John B. and James T. Battles from Niles, Michigan; Manuel P. and Alexander Jackson, also brothers from Chillicothe, Ohio; and Nimrod Eaves of Boonesville in Albemarle.

John Bolden Battles was born to free parents Robert and Mary Battles on June 7, 1833, in Charlottesville, Virginia. James T. Battles, his younger brother, was born July 29, 1839, also in Charlottesville. The Battles family left Albemarle County at some point after 1850 settling temporarily in Ohio. Sometime before 1860 after their parents’ death, the Battles brothers and their sister moved to Michigan. John married Barbara Winborn on June 10, 1857 in Lawton, Michigan. Prior to enlisting, James lived with John and Barbara in Niles, Michigan, where the two brothers worked as carpenters. James additionally peddled produce he grew himself in order to supplement his income.

At the age of thirty-one, John enlisted as a private in the Union army on August 31, 1864 in Niles and mustered in on September 5 in Kalamazoo. Twenty-five-year-old James enlisted soon after his brother on September 1 and likewise mustered in on September 5. The two brothers’ service records list them both as 5 foot 11 inches at the time of their enlistment with black hair, black eyes, and black complexions. The Battles brothers served in Company B of the 102nd Regiment Infantry, USCT. They both enlisted for a period of one year, during which John achieved the rank of corporal on November 1. James Battles remained a private during his service in the war. Prior to serving at Honey Hill, John and James served in Florida, participating in a raid on the Florida Central Railroad in August 1864 before moving with their regiment to Beaufort County, South Carolina.

Manuel P. (Emmanuel) Jackson was born into slavery around 1840 in Albemarle County, Virginia, to parents James and Patcy Jackson. His younger brother Alexander Jackson was born around 1843 also in Albemarle. According to Manuel, sometime before 1854 the Jacksons’ owner “liberated” them. The Jackson family promptly moved to Chillicothe, Ohio, where the two brothers worked on their father’s farm.

Both Jackson brothers enlisted as privates on June 5, 1863, Manuel at the age of twenty-three and Alexander at the age of twenty, and mustered in on June 10 in Readville, Massachusetts. At the time of enlistment, their service records describe Manuel as 5 feet 8 1/2 inches with hair, brown eyes, and dark complexion and Alexander as 5 feet 7 inches with black hair and eyes and dark complexion. The brothers served in Company G of the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the sister regiment of the famous Massachusetts 54th. Like many other free blacks in Ohio, the two brothers joined regiments out of Massachusetts because it was the first free state to raise all black units. Before Honey Hill, the 55th Massachusetts served extensively in South Carolina and in Jacksonville, Florida. On October 7, 1864, Alexander wrote a routine letter to his aunt asking if she had received the $450 he and his brother had sent back home for safe keeping. It is the only personal wartime letter of any black soldier from Albemarle County known to exist.

Nimrod Eaves was born around 1839 in Albemarle County, Virginia. According to his pension record, Eaves lived in the tiny village of Boonesville in western Albemarle for five years prior to enlisting, where he worked as a laborer and a farmhand. According to the 1860 US Census, Eaves was a freeman living in the household of a Rice Keller. He married Lucy Goings in March of 1861, but the two soon divorced around 1862.

Eaves enlisted at the age of twenty-five as a private on October 13, 1864, in Camp Casey, Virginia, and mustered in five days later. His enlistment record describes him as 5 feet 5 inches with brown hair, black eyes, and yellow complexion. Eaves served in Company K of the 34th Infantry Regiment USCT. Soon after he mustered in, Eaves transferred to Florida, where he would serve at Jacksonville, Palatka, and Magnolia Springs until 1864 when the 34th moved to Hilton Head, South Carolina, to join the Boyd’s Neck Expedition. Soon after joining the expedition, Eaves served with the Jackson and Battles brothers at the battle of Honey Hill.

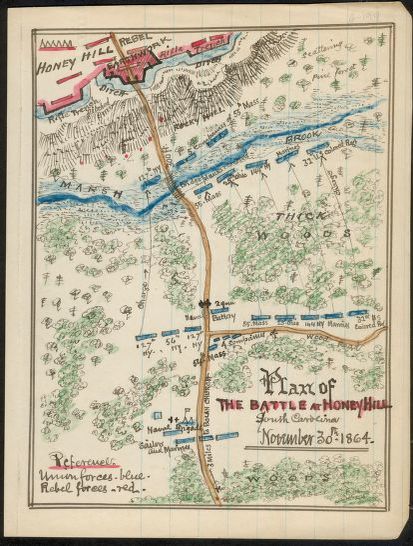

On November 12, 1864, Lieut. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant approved Sherman’s plan for an expedition up the Broad River. Sherman ordered Maj. Gen. John G. Foster to carry out the attack to cut the railroad connecting Charleston and Savannah. Foster planned to move his forces out from Port Royal Sound on November 28, land the next day at Boyd’s Landing, and attack the railroad depot at Gopher Hill near Grahamville. An injured Foster gave field command to Brig. Gen. John Hatch, who split his force into three brigades: two of infantry regiments and one artillery regiment. The army forces were additionally supported by a brigade of sailors, marines, and naval artillery from Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren of the South Atlantic Blocking Squadron.

The first brigade led by Brig. Gen. Edward E. Potter, was comprised of the 25th Ohio Infantry, the 56th and 144th New York Infantry, the 157th New York Volunteer Infantry, and the 32nd, 34th, and 35th USCT. The second brigade, led by Col. Alfred S. Hartwell of the 55th Massachusetts, contained the 54th and 55th Massachusetts and the 102nd USCT. Albemarle County natives present at the battle included Robert Brock and Samuel Martin of the 32nd USCT, Nimrod Eaves and William Smith of the 34th USCT, John and James Battles of the 102nd USCT, and Horace Goins, Robert, Manuel, and Alexander Jackson of the 55th Massachusetts. James Davenport of the 54th Massachusetts was also with his regiment at this time, but he was serving as a company cook and almost certainly did not participate directly in the fight.

The regiments with Albemarle-born black soldiers assembled in the Port Royal Sound leading up to November 28, with the 54th and 55th Massachusetts arriving from Charleston, the 32nd USCT from Hilton Head, the 34th and 35th USCT from Jacksonville, and the 102nd USCT from Beaufort. The men and officers once assembled had less than two days to prepare and carried limited ammo and rations for what they were told would be a short trip. As described by historians Stephen R. Wise and Lawrence R. Rowland, a soldier characterized it as a “wait-till-tis-dark-and-don’t-say-a-word-about-it” plan, typical of Sherman’s Department. Foster and Hatch planned to have Dahlgren’s naval forces set out first to secure Boyd’s Landing as a beachhead.

Heavy fog on the night of November 28 prevented Dahlgren and the naval ships from leaving until 4:00 AM the morning of November 29. The army transports’ journeys were fraught with many problems as well. Army transport ships suffered from faulty maps, inept pilots and no local guides. These detriments compounded to cause several transports to make wrong turns along the Broad River, resulting in many hours lost due to correcting course and righting ships that had run aground. Altogether, Hatch lost over a day, which allowed the rebel forces to regroup and reinforce the area surrounding the depot at Gopher Hill.

The rebel strategy for protecting against a landing of Union troops had been to have cavalry patrol coastline and shores to discover the enemy’s landing site, alert the army, and man fortifications with local garrisons until reinforcements could arrive. By the time Hatch’s forces encountered the rebels, some 1,400 men of the 1st Brigade Georgia Militia, the Georgia State Line, and the Athens and Augusta Georgia Reserve Battalions had come to defend the depot at Gopher Hill. The road approaching the depot forked right before passing Honey Hill. This allowed the rebels to fortify the two lunettes atop the hill with artillery and infantry, unseen by anyone advancing up the road. Thus, Hatch’s Union forces would face tough resistance in their endeavor.

Despite the unforeseen setbacks and logistical errors, the Union expedition started successfully. Dahlgren’s forces of naval soldiers, marines, and artillery managed to secure Boyd’s Landing to prepare for the infantry’s advance. Hatch’s regiments arrived sporadically. Despite not yet having the 34th and the 102nd present, Hatch remained determined to take the depot by the night of November 30 set off at daylight. The action that day began with an artillery duel ahead of Honey Hill between the Confederates and the guns of the 3rd New York Artillery. The 32nd USCT, at the head of the column, charged up the road as Potter’s 1st Brigade advanced. Dense woods and undergrowth on both sides of the road obscured enemy infantry, but the Union forces were nonetheless able to advance. Around noon, the brigade was finally able to make the turn to the west on the road to meet the main enemy line, but in doing so exposed itself to the unseen artillery atop Honey Hill.

After the turning movement, the 32nd on the north side of the road was the most exposed position on the battlefield. The 35th under Col. James C. Beecher, half-brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, formed up and attempted to advance up Honey Hill. The rebel artillery zeroed in on the 35th and fired, with the first shot hitting like a “bulls eye” according to Maj. George T. Jackson, commander of the Augusta Reserve Battalion. Several men were immediately killed and wounded. The shots killed Beecher’s horse and hit him in several places, including severing his femoral artery. As the 35th retreated to safety behind the artillery, a doctor advised Beecher to retreat from the field, to which the colonel refused. After the 35th failed to advance, Potter attempted to deploy the 32nd forward, but they were unable to advance past a rebel earthwork.

Early into the afternoon, Col. Hartwell arrived with several elements of his brigade. Hartwell moved first to support the 35th behind the artillery, but then prepared the 54th and 55th to support the 127th New York to flank the top of Honey Hill and sweep the rebels forces off. However, the 54th veered too far to the left and ended up mixing their lines with troops of the 144th New York and 25th Ohio, a rare example of black and white troops fighting side by side. Due to confusion, Hartwell with the 55th Massachusetts and the 127th New York attacked up the hill, without the intended support of Battery F of the 3rd New York Artillery and the 54th Massachusetts.

Optimistically, Hartwell, Capt. Crane and Lt. Hill lead the five companies of the 55th forward. The 55th “cheerfully” followed, according to Hartwell, and Crane encouraged them yelling. “Come on boys, they are only Georgia militia!” Hartwell shouted, “follow your colors” before the column was immediately torn apart by artillery and small arms fire, killing Crane and severely wounding Hartwell. As the 55th advanced the color sergeant was killed. Corporal Andrew Smith managed to pick up the colors and inspire his comrades by carrying them for the rest of the battle. Smith later won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his deed. Pvt. Elijah Thomas and Lt. Thomas F. Ellsworth managed to extract Hartwell from the battlefield and save his life. Thomas was killed in the act and Ellsworth later received the Medal of Honor. In total, the charge did not even last ten minutes and around two thirds of the attackers in the 55th were killed or wounded. The 55th’s attack allowed the 127th to make it to the top of Honey Hill, but the rebel forces managed to push them back.

Sometime later, the 34th finally arrived on the battlefield and advanced toward Bee’s Creek. Under Lt. Col. William W. Marple, they managed to hold off advancing enemy cavalry and held the Union line until nightfall. Around the same time as the 34th entered the battle, the 102nd also arrived. The 102nd was tasked with retrieving the guns of the 3rd New York Artillery from the field, who had only managed to bring one back. The regiment’s men managed to recover some of the 3rd’s artillery pieces by dragging the guns back under heavy fire by hand, without the aid of draft animals. A Lt. Orson W. Bennett of the 102nd won the Medal of Honor for advancing more than 100 yards under heavy fire during this action. Running low on ammunition and knowing of incoming rebel reinforcements, Hatch began ordering retreat regiment by regiment. By the morning of December 1, the Union forces had fallen back to a fortified position at Boyd’s Landing.

Days later, the rebels surveyed the battlefield. General Baker claimed he had “never in any previous battle seen such evidence of terrible havoc from artillery.” A Lt. Zealy claimed that the Union corpses “lay five deep dead as a mackerel.” Union forces suffered eighty-nine dead, six hundred and twenty-nine wounded, four missing, and twenty-eight captured. Robert Jackson of the 55th, an Albemarle County native who was apparently not related to Alexander or Manuel, received a gunshot wound at the battle that would ail him for the rest of his life. Of the three prisoners captured from the 54th Massachusetts, two of them were executed. The other, a former slave, was returned to his previous owner in South Carolina. The rebels buried the white bodies in shallow graves and left the black troops to rot. Some planters even brought their slaves to view the dead soldiers to discourage them from escaping to Union lines.

Much like the 54th Massachusetts’s experience at Fort Wagner, the abolitionist and northern black press celebrated the USCT’s heroism at Honey Hill. Sergeant Charles Lenox of the 54th who was at both battles claimed, “Wagner always seemed to me the most terrible of our battles…but the musketry at Honey Hill was something fearful.” William Lloyd Garrison, father of a lieutenant in the 55th and editor of the abolitionist Liberator, described the 54th as “heroes of all the hard fights that have occurred in [Sherman’s] department since their arrival.” He also applauded the 55th’s bravery in the face of the heavy rebel resistance. “The fire became very hot, but still the regiment did not wave—the line merely quivered.” Many months after the battle, the Christian Recorder published a letter from a Corporal T. B. C. of the 32nd USCT. The corporal wrote that that the 32nd “proved as brave as any other regiment in the brigade” at Honey Hill, even though it was the regiment’s first battle, where “many a brave men fell, nevermore to rise.”

Following the federals’ defeat, Gen. Hatch regrouped his forces. They tried twice more with a demonstration against the Charleston and Savannah Railroad from December 6-9 and an expedition at Deveaux’s Neck on December 6 at which the men of the 32nd, 34th, 102nd, and 55th were present. However, the Union forces were unsuccessful both times. By December 21, Sherman learned of the rebel evacuation of Savannah and ordered his subordinates to occupy the city. The expeditions at Boyd’s Neck and Deveaux’s Neck may not have achieved their primary objects, but they did succeed in diverting and spreading the defending rebel forces.

Afterward, the four regiments as well as the 54th Massachusetts continued to serve along the Atlantic Coast throughout the following year. The 32nd, 54th, and 55th all mustered out of service that August, with the 102nd following suit at the end of September. The 34th was the last to leave the service in late February 1866. All of the Albemarle-born men in these regiments survived the war with the exception of Alexander Jackson. Alexander died of “inflammation of the lungs” on March 5, 1865, at a hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina. His father, James, received his son’s unclaimed bounty money but was unable to obtain a parent’s pension in the early 1870s.

After the war, Nimrod Eaves returned to Albemarle County, but many Albemarle-born men like the Battles brothers and Manuel Jackson returned to their northern homes for the rest of their lives. Like many black veterans in the North or South, the four men’s once healthy bodies were permanently damaged by their service. In seeking to take care of themselves and their families, they faced the common struggle of securing pensions in a system that was prejudiced against black applicants who were often illiterate or had no paper records of their birth or marriages. The debilitating medical conditions these black veterans suffered due to their service often were so great that they prevented the former soldiers or their families from being able to support themselves. Both of the Battles brothers and Manuel Jackson were forced to seek financial aid or medical help in federally-run soldiers’ homes.

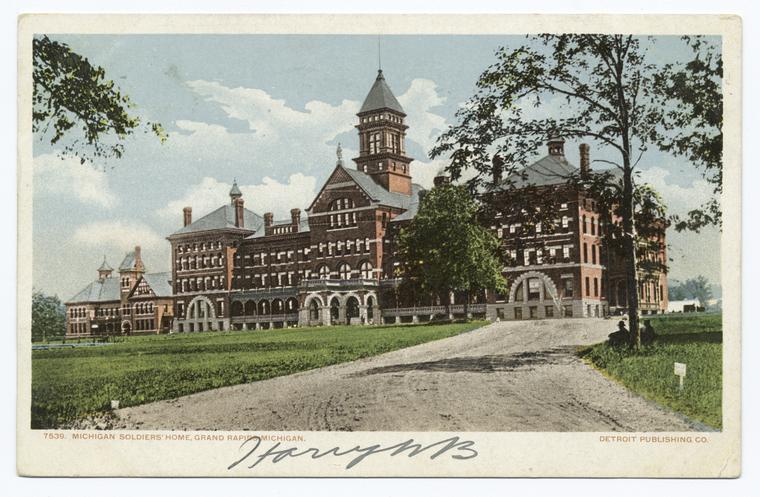

After mustering out of the army, the Battles brothers returned to Niles, Michigan. John Battles moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1875 to live until 1901, when he moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to live in a soldier’s home. He applied for a pension in 1887, describing himself as “nearly totally” disabled due to piles and received $15 a month by 1907. Battles died on February 19, 1908 in the Grand Rapids Soldiers Home of jaundice. His wife Barbara received a pension until her death in Chicago on June 24, 1911.

After returning to Niles at the end of the war, James Battles married Sarah Francis Finley of Cass County on April 14, 1867. Together they had six children. Battles worked, according to his pension testimony, at “hard manual labor” and occasionally did “some garden trucking.” He also spent time living in Traverse City, Michigan; Chicago; and, like his brother, the soldier’s home in Grand Rapids. Despite his tall and strong stature, his pension record suggests he suffered from rheumatism. Battles’s wife Sarah died on April 22, 1897. He had difficulty securing a pension, but began receiving payments in 1907 that steadily increased to $20 a month by June 3, 1912. He died on December 19, 1913 of apoplexy in the soldier’s home in Grand Rapids. Local white members of the Samuel Judd Grand Army of the Republic post, a veteran’s organization, attended his funeral and burial. A local newspaper, the Newaygo Republican, remembered James as having “a kindly disposition and a fund of ready wit, he made friends of all with whom he came in contact and he will be greatly missed.” He is buried in Newaygo County, Michigan.

After mustering out of the army, Manuel Jackson returned to Ohio, living in Martinsville for most of his life until moving north to live in a veterans’ home in Erie County. Jackson suffered from a spinal disease and before moving to the soldiers’ home he had treated himself for his ailment due to his inability to pay for a medical treatment. He began receiving a pension of $2 a month in 1887 that increased to $12 a month by 1890. Jackson died of unknown causes sometime in 1897, likely at the soldier's home in Erie County. There is no record of Manuel Jackson ever marrying or having children.

After the war, Eaves returned to Albemarle County, working as a farm laborer and a shoemaker. On April 1, 1877, Eaves married Lizzy Yauncey in North Garden, a small village located southwest of Charlottesville in Albemarle County. They had no children. His first application for a pension in 1881 was denied to a lack of evidence to furnish his claim. Eaves successfully reapplied in 1891 and received a pension of $6 per month for “malarial poisoning and rheumatism” contracted during his service in the operations against Jacksonville. He died of unknown causes sometime between May and June 1898, likely in or near Charlottesville.

In addition to their service at Honey Hill, these free African-American troops born in Albemarle County shared common experiences of struggle before and after the war. Although several of them had been born into slavery, they all embraced freedom prior to the outbreak of war, striving to support themselves as free men. At Honey Hill, the men struggled against well-entrenched Confederate positions, fighting a fearsome battle made worse by poor decisions by Union commanders on the ground. Following the war, they struggled to make ends meet and ended up needing government aid from pensions or soldiers’ homes just to survive. Nevertheless, their struggles helped win freedom for others of their race still in bondage and left a legacy of heroism and endurance for their children or local black communities.

Matt Wallace is a fourth year undergraduate student at the University of Virginia, studying History and participating in the Distinguished Majors Program for Politics. As a 2018-2019 Sewell Undergraduate Intern for the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History, Matt researched the history of Albemarle County and UVA during the war.

Images: (1) Map of Battle of Honey Hill (courtesy Library of Congress); (2) Alexander Jackson to His Aunt, October 7, 1864 (courtesy National Archives); (3) Nimrod Eaves in 1860 Census (courtesy Ancestry.com); (4) Excerpt from Robert Jackson's Compiled Military Service Record (courtesy National Archives); (5) Grand Rapids Michigan Soldiers Home (courtesy New York Public Library).

Sources: Compiled Service Records for James T. Battles, John B. Battles, Robert Brock, James Davenport, Nimrod Eaves, Horace Goins, Alexander Jackson, Manuel Jackson, Robert Jackson, Samuel Martin, and William Smith, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed through Fold3 https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for James T. Battles, John T. Battles, Nimrod Eaves, Robert Jackson, and Manuel Jackson, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Nimrod Eaves and Lizzy Yauncey Marriage Certificate, April 1, 1877, Albemarle County Courthouse, Charlottesville, Virginia; The Christian Recorder, April 29, 1865, accessed through Accessible Archives, https://www.accessible-archives.com; The Liberator, December 16, 1864, accessed through 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, https://www.gale.com/c/19th-century-us-newspapers; Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959); Douglas R. Egerton, Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America (New York: Basic Books, 2016); Donald R. Shaffer, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004); Stephen R. Wise and Lawrence S. Rowland, Rebellion, Reconstruction, and Redemption, 1861-1893: The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina, vol. 2 (Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press, 2015).