From Carter’s Mountain to Morganza Bend: A U.S.C.T. Odyssey (Part I)

by Elizabeth R. Varon | | Wednesday, January 11, 2017 - 13:04

Note: What follows is a three part story, which we will present in consecutive blog posts, that permits us to see the history of central Virginia in a new way: with a focus on the journeys of African American men, born in the shadow of Jefferson’s Monticello, who fought for the Union army in the Civil War. These men represent the Virginia roots of thousands of U.S.C.T. soldiers, men who were dispersed by the system of slavery and then converged, during the war, in black regiments, and fought to save the Union and to end slavery.

Part I: Enlistment

Eighteen Albemarle-born African American men who were slaves of Thomas Jefferson’s descendants and of Jefferson’s extended family served together in Missouri U.S.C.T. regiments in the Civil War.

On December 7, 1863, Daniel W. Carter, 26 years old, fled the Missouri plantation where he was enslaved and made his way to the Union army recruiting station at Troy, Missouri, joining Company K of the 62nd U.S. Colored Troops. A few days later, he was followed by Robert Jackson and Lewis Carter, both age 21, Warner Carter (22), Winston Jackson (26), Spencer Scott (30) and Abner Watson (33), who enlisted at Troy on December 10, 1863, and were then mustered into Company A of the 65th U.S.C.T. at Benton Barracks, St. Louis on December 18, 1863. Robert, Winston, Spencer and Abner entered the enlistment rolls under the name “Carter” rather than with their original surnames; whether this was at the behest of the Union recruitment officers or the men’s own choice—and whether “Carter” was an alias or assigned name, rather than the family name, of others of these recruits—remains unclear.

All seven men were the slaves of John Coles Carter, who was married to Thomas Jefferson’s great granddaughter Ellen Monroe (Bankhead) Carter. His own family was part of Virginia’s elite: John Coles Carter was the great great grandson of Robert (King) Carter, the wealthiest man in colonial Virginia, and great grandson of John Carter, who owned nearly 10,000 acres in Albemarle County, centered at Carter’s Mountain. As the ancestral estates of the Virginia gentry were being subdivided among descendants, slaveholders looked west for additional lands to turn into plantations. John Coles Carter inherited 1,500 acres in Pike and Lincoln counties in Missouri from his mother Mary Eliza Carter, and he migrated from Virginia to Missouri in 1852. Census records show that he owned 103 slaves in Albemarle County in 1850; these slaves, in their forced migration west with Carter, would have moved through the Cumberland gap into Kentucky and then travelled by boat and raft on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to Missouri. By the eve of the Civil War, John Coles Carter had 126 slaves working his lands in Pike and Lincoln counties in Missouri (part of the state’s “Little Dixie” plantation belt), growing tobacco, wheat and corn. Carter settled near other families that had migrated from Albemarle County to Missouri, including the family of his brother-in-law John Warner Bankhead, Thomas Jefferson’s great grandson. Bankhead, who was educated at the University of Virginia, migrated from Albemarle County to Missouri in 1842; his sister Ellen Bankhead was John Coles Carter’s wife.

In a second wave of U.S.C.T. enlistments in January of 1864, slaves of John Warner Bankhead, of John Coles Carter, and of Carter’s son John Jr. all made their way to Union recruiting stations. Charles Bankhead (39) and George Bankhead (25) both enlisted at Louisiana, Missouri on January 18, 1864 and mustered into Company E of the 67th U.S.C.T. at Benton Barracks on January 29, 1864 (a Spencer Bankhead attempted to enlist but was turned away for being disabled and medically unfit). That same day in January of 1864 four more men—Jacob Carter, age 17, Mathew Carter, also 17, Liberty Brown Carter (19) and Jackson Carter (25)—also enlisted in Louisiana, Missouri; they too mustered into Company E of the 67th U.S.C.T. at Benton Barracks on January 29, 1864. John Coles Carter owned Jacob and Mathew and his son John Carter Jr. owned Jackson and Liberty, whom his parents deeded him when he turned 18 in 1858. Ten days later, William J. Carter (26), also owned by John Coles Carter, enlisted in Co. A of the 67th on Jan. 28, 1864 at Louisiana, Missouri.

In late February of 1864, another Carter slave, Bradford Carter, enlisted, mustering into Company A of the 65th regiment. Three more such enlistments would come in the spring, summer and fall of 1864: George Scott enlisted in Company F of the 68th U.S.C.T. in Louisiana, Missouri on May 10; William Tucker mustered into Company F of the 18th U.S.C.T. at Benton Barracks on August 30; and Thomas Brown enlisted in Company G of the 18th that September. All were slaves belonging to John Coles Carter at the time of their enlistments.

These enlistments came on the heels of Union General John M. Schofield’s November 1863 General Order 135, which authorized the Federal army in Missouri to sign up “any able-bodied man of African descent, slave or free, regardless of the owner’s loyalty or consent, with freedom for slave enlistees and compensation for loyal owners.” Missouri, as a loyal slave state, was exempt from the provisions of the Emancipation Proclamation—but African Americans there did not heed this exemption, and flocked to Union lines to enlist, prompting the General Order, which clarified that all soldiers would be granted freedom. In part because Schofield and his successor as commander of the Department of Missouri, General William S. Rosecrans, prohibited the use of mobile recruiting parties, slaves “wishing to enlist had to weigh the risk of being captured by armed patrols” of slave hunters in order to reach recruiting stations such as the one at Louisiana; those who were tracked down by such patrols were whipped and returned to their masters, or shot in cold blood. Moreover, slaves who sought to enlist had to leave behind their own families, at the mercy of masters, potentially “to be abused, beaten, seized and ….and deprived of reasonable food & clothing because of their Enlistment,” as a petition of white Unionists in Louisiana, Missouri reported to General Rosecrans in February of 1864. The flight of Missouri slaves to Union lines in 1864 and 1865—over 8,000 in all—helped to convince many white Missourians that slavery “had reached its limit,” and on January 11, 1865, a Missouri constitutional convention enacted immediate emancipation of all slaves without compensation to their owners.

But that victory was still a long way off when the Carter and Bankhead men joined the Union army in the winter of 1863/64. The men who trained at Benton Barracks participated in a procession in St. Louis on January 1, 1864 marking the first anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation; as a correspondent to the Christian Recorder wrote, they marched to the “music of John Brown’s Soul is Marching On.” At the end of January, a “grand review of colored troops” took place at Benton Barracks; “a nobler set of men cannot be gathered anywhere,” the Christian Recorder correspondent noted with pride. The next phase of the men’s journey would take them to Morganza, Louisiana—one of the deadliest locales, for Union soldiers, in the Deep South.

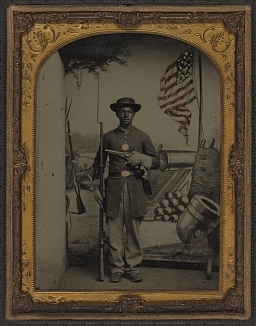

Image: An unidentified U.S.C.T. soldier at Benton Barracks (Library of Congress).

Sources: Compiled Service Records, RG 94 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed for each soldier through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Robert Carter, Winston Carter, Warner Carter and Spencer (Scott) Carter, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Charles Tromblee, “John Coles Carter and Family--The Missouri Years” (2012), accessed at Virginia Historical Society; B. Noland Carter II, A Goodly Heritage: A History of the Carter Family in Virginia, Vol. I (2003); Ira Berlin et al., Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (1992); Christian Recorder (Philadelphia), Jan. 30, 1864; William A. Dobak, Freedom By the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867 (2013); Margaret Humphreys, Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War (2010); John David Smith, ed., Black Soldiers in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era (2002); Diane Mutti Burke, On Slavery’s Border: Missouri’s Slaveholding Households (2010); Lincoln County (Mo.) Herald, March 12, 1868; Larry M. Logue and Peter Blanck, “’Benefit of the Doubt’: African-American Civil War Veterans and Pensions,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History (Winter 2008).