"Good and Faithful Union Men": The Struggle to Forge a Republican Coalition in the Reconstruction South

by Clayton J. Butler | | Thursday, March 21, 2024 - 11:45

In the spring of 1867, Americans found themselves navigating uncharted political waters. Two years after the fighting between Union and Confederate forces had ended, the country remained deeply divided over how to move forward. President Andrew Johnson’s approach to Reconstruction had failed. The Republican wing of Congress, frustrated with the president’s accommodation of rapidly rehabilitated and largely unrepentant former rebels, had taken control of Reconstruction policy and set new terms for the readmission of the late Confederate states to participation in the national government. The states that had seceded would have to adopt new constitutions, ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, and – most importantly – they would have to enfranchise Black men. It was a revolutionary, epoch-making bombshell, and partisans of every political stripe moved to position themselves in the new electoral landscape.

White Southern Unionists occupied a pivotal place in this rapidly changing state of affairs. Thousands of Southerners had risked life and limb to support the Union cause during the war but, two years on from Appomattox, it seemed to have done them little good. After the war, returning former Confederates harassed them and shut them out from public office, seizing control of the political machinery and reconsolidating power in the hands of the conservative Democratic Party. At times Unionists suffered violent reprisals for their wartime opposition to the Confederacy. They needed a way to break the stranglehold that their former Confederate foes, ostensibly vanquished in 1865, had all but reestablished on politics in the South.

Unfortunately for their electoral prospects, unconditional Unionists had always constituted a distinct minority in the states of the Confederacy, especially in the Deep South. With the war over and former Confederates back home, Unionists found themselves outnumbered and outvoted once again; subject to violence and intimidation just as they had been during the secession winter of 1860-61. It was, many felt, as though they had lost the war. Then, early in 1867, Congress finally intervened to deal former rebels a stunning blow. The First Reconstruction Act, passed over President Johnson’s veto, mandated that the process of readmission would essentially have to start over from scratch. This time, however, Black men would participate—a dramatic change to the political calculus.

Republicans’ sudden enfranchisement of hundreds of thousands of Black voters created a new constituency overnight, one finally capable of mounting an effective opposition to the Democratic Party in the South. A Republican alliance between former Unionists and freedmen now presented a viable path to power. But would they take it? Despite their shared wartime opposition to the Confederacy, white Unionists and Black Southerners often proved reluctant collaborators. Black voters had well founded misgivings about their prospective political partners and their goals. White Southern Unionists, though they had vociferously opposed secession, had raised no immediate objection to slavery, per se, at the outset of the war. Some had even based their Unionism on the defense of slavery, arguing that the institution would be better protected within the Union than out of it. Over the course of the conflict, they had come to condone emancipation as a necessary war measure, just punishment, and future check on slaveholding secessionists—but they retained a deep-seated racism toward African Americans that the war did nothing to alter. How would this tenuous coalition, thrust together by circumstance, negotiate the new postwar political environment? Would the maxim that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” sustain a lasting partnership?

In May 1867, a group of former Unionists called a public meeting at Mount Hermon Church in Washington Parish, Louisiana, to present their candidates for the upcoming state constitutional convention and to make their case to the voters of their district. Reprinted in The New Orleans Advocate, the speech they gave sheds valuable light on the profound uncertainty, the breakneck speed of social change, and the stakes of the political contest then unfolding in the first years of Reconstruction.

First, the speaker reminded the crowd what had brought them to the present point, where “the political womb is now pregnant with the most important events; whether for weal or woe, none at present can determine.” Following the war, former Confederates who had carried on “their insane crusade against liberty” for four years had promptly reassumed their former political positions and heedlessly antagonized those who, in victory, offered terms of peace “fuller of magnanimity and generosity than any before offered to a conquered people.” The Unionist party in Louisiana, the speaker reminded the crowd, had suffered – and continued to suffer – “simply because we refused to apostatize from that glorious old faith that has made the names of Jackson, of Webster, and Clay, immortal.” But the recalcitrant Democrats, as all knew, had overplayed their hand. Congress “declared its ultimatum” and the voters of the state – white and Black – now had an opportunity to restore government to the party that had “lifted the dark cloud of despotism that rested over us . . . [and] torn away the gyves [shackles] of oppression that Confederate authority was forging upon your hands, and ours.” To do this, white and Black Unionists would have to vote as one, and to that end the speaker directed the following remarks:

“To our colored friends who have so suddenly and unexpectedly been clothed with the privilege of the elective franchise, we would fain address a few remarks. To those of your friends who reside near and among us, no remarks are necessary. We are frank to admit that the prejudices of our birth and education induced us to be opposed (not to your freedom) but to your enfranchisement at the present time; but the thing is accomplished, and you are voters. We do not say we will do everything for you, but we do promise to respect your rights, and will labor for your political and educational promotion. The same power that strove to eternize your bondage also sought our degradation. We are identified in principle with that great and powerful party that has emancipated you. As we have ever fought against the power who strove to keep you slaves, we surely have larger claims upon you than the opposite party. Born upon the same soil, and raised to labor under the same burning sun with yourselves and having, like you, been relieved by federal success from a position of great peril, we can quite fully appreciate your condition. We earnestly solicit your support for the good and faithful Union men whose names are now placed before you as candidates for office.”

With this speech the white Unionists of Washington Parish came to grips with a political situation none could have anticipated just a few years before. It is a remarkable document of an extraordinary time. Its greatest significance, though, lies in its expression of Unionists’ profound ambivalence toward Black men as full political partners, one that would ultimately doom the Republican Party in the Deep South. It is a striking fact that the Unionist speaker at Mount Hermon Church that day made an earnest appeal for the votes of Black men who he could not even say deserved to have the vote at all. Former Unionists had shown themselves willing to ally themselves with African Americans during the war to defeat the Confederacy and save the Union, but the lengths they would actually go to sustain African Americans’ civil rights afterward – with the Union successfully restored – represented a different proposition altogether.

For a few years after 1867 the Republican coalition did manage to hold sway in Southern politics, enacting new state constitutions and passing a raft of progressive legislation. In the end, however, faced with social ostracism and the constant threat of violence, the coalition collapsed in every state of the former Confederacy. Numerous factors contributed to the eventual defeat of “radical” Reconstruction and the recapture of the South by the Democratic Party, but prominent among them, it must be said, was white Southern Unionists’ inability or unwillingness to conceive of Black men as political equals and full citizens. As one Freedman’s Bureau official had noted, “there seems to be a strong desire to get back into the Union but they don’t want the black man to have anything to do with it.” [1]

Over the course of Reconstruction, southern Democrats deliberately played on Unionists’ palpable ambivalence. They made a persistent and ultimately successful appeal to white solidarity that proved attractive even to former foes. Antipathy toward the Confederacy, they knew, had not and did not equate to sympathy for African Americans or unqualified support for their civil rights. White supremacy crossed lines of national loyalty and had more purchase in the South (to say nothing of the nation as a whole) than the Confederacy ever did. Understanding this seemingly counterintuitive fact is crucial to understanding the subsequent course of American history. Though a considerable core of white Unionism revealed itself during the war, no such core of white support for civil rights had lain behind it. Unionism and Black civil rights represented two separate causes to nineteenth-century Americans, and Southern Unionists, who risked and suffered more than Northerners to maintain their national loyalty, force us to reckon with this better than anyone.

Clayton J. Butler is Marketing and Sales Associate at the University of Virginia Press and the Assistant Editor for The American South Series and A Nation Divided: Studies in the Civil War Era. He is the author of True Blue: White Unionists in the Deep South during the Civil War and Reconstruction (LSU Press 2022).

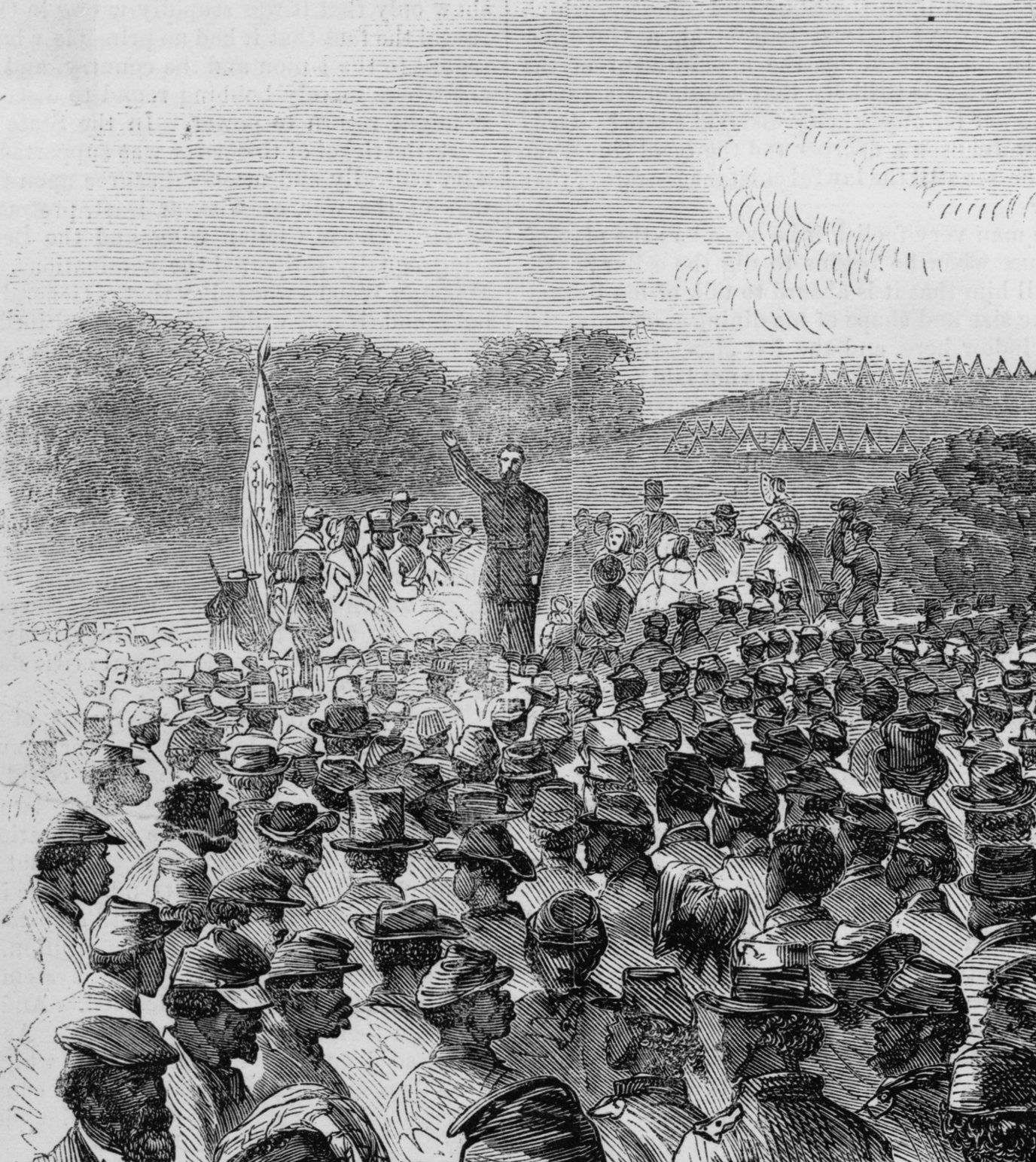

Image: "The war in the southwest - Adjutant-General Thomas addressing the Negroes in Louisiana on the duties of freedom," Harper's Weekly, November 14, 1863

Notes: [1] W. T. Esoing to Charles Buckley, May 14, 1867, reel 3, “Unregistered Letters,” Records of the Superintendent of Education for the State of Alabama, RG 105.