The Pieces-and People-of the Confederacy: Interning at the American Civil War Museum

by Evelyn Garey | | Thursday, August 31, 2023 - 09:17

I am, first and foremost, a storyteller. It perplexes me that some people can’t seem to comprehend my love for both history and theatre when they share so many similarities. Both ask questions, study behavior, and seek the truth: importantly, both are in the business of people.

History and theatre tell us who we are and why it matters. They tell stories with purpose.

So, when I interviewed with Mr. Christopher Graham, the Curator of Exhibitions at the American Civil War Museum (ACWM), and he pointed to the one word he had written on my application- “storyteller”- I knew this internship would be a great fit.

My summer with the American Civil War Museum has been a joy and an honor. Chris and his team gave me every opportunity to contribute to the world of the museum through its artifacts, exhibits, and visitor goals. I’ve gained a deeper understanding and appreciation not just for the Civil War, but also for the hard work that goes into telling a historical story to a diverse audience. Through my work, I’ve grown as a historian, a storyteller, and a person. I am certain to cherish this experience- a pivotal moment in my early career and young adult life- for years to come.

Chris gave Yashita Keswani, my fellow Nau Center intern, and I two different projects, each suiting our interests and goals for the summer. Yash, who plans to attend law school, was given the opportunity to conduct thorough research reports on the latest scholarship on the war. With my interest in creative writing and the human narrative, Chris charged me with the task of researching war artifacts and writing the stories of their owners. The American Civil War Museum was formerly known as the Museum of the Confederacy, and a large portion of its artifacts originated in the South. Many were donated shortly after the war for preservation and memory. Provided with only bare-bones information about the donor and a few “clues” as to where to look, I scoured databases like Ancestry.com, Fold3, Find a Grave, and Newspapers.com for more information on the people behind the object. What would start as a hat, mourning dress, or helmet always seemed to morph into something much bigger:

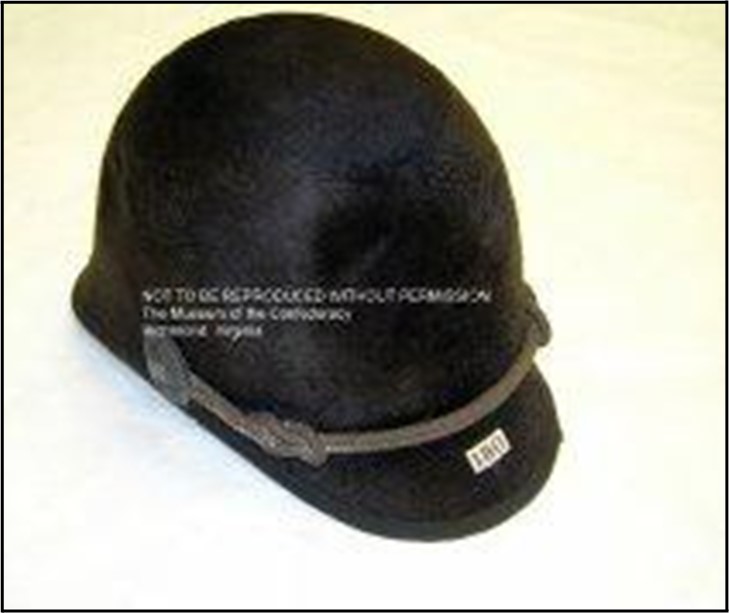

Edwin Calhoun of Abbeville, South Carolina, was a “Dixie Ranger'' for the 6th South Carolina Cavalry. Calhoun sustained a life changing injury in the battle of Trevilian Station on June  11, 1864. Calhoun was not originally chosen to fight, but he swapped places with an ailing friend. The opposing Union army possessed a distinct advantage over the 6th South Carolina Cavalry, seizing both the depot and house for defense. One enemy soldier climbed a tree and rained fire over Calhoun’s fellow soldiers. As Calhoun began to switch cartridges, he was shot in his left temple and passed out. The bullet traveled through this hat and into his head. As Calhoun later wrote, “The hole is there today. When I was shot, the ball passed through the brim of my hat, carrying a piece of wool with it. Unknown to me or to the doctors, this piece of wool remained in my wound, irritating it and keeping it from healing. The only wonder is that I did not have blood poison. Sometime after the bullet had been removed, the wool worked to the hole and I pulled it out with my finger.” Calhoun lived to the age of 78 and celebrated his 50th wedding anniversary.

11, 1864. Calhoun was not originally chosen to fight, but he swapped places with an ailing friend. The opposing Union army possessed a distinct advantage over the 6th South Carolina Cavalry, seizing both the depot and house for defense. One enemy soldier climbed a tree and rained fire over Calhoun’s fellow soldiers. As Calhoun began to switch cartridges, he was shot in his left temple and passed out. The bullet traveled through this hat and into his head. As Calhoun later wrote, “The hole is there today. When I was shot, the ball passed through the brim of my hat, carrying a piece of wool with it. Unknown to me or to the doctors, this piece of wool remained in my wound, irritating it and keeping it from healing. The only wonder is that I did not have blood poison. Sometime after the bullet had been removed, the wool worked to the hole and I pulled it out with my finger.” Calhoun lived to the age of 78 and celebrated his 50th wedding anniversary.

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Susan Smith of Beachland, Virginia, lost three relatives during the Civil War, though none died in direct combat. The passing of her father, sister, and uncle within the span of one year left Lizzie in mourning for years to come. The loss of her uncle, Sands Smith II, was particularly noteworthy and traumatic. On October 7, 1863, Smith encountered several Union soldiers belonging to the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Attempting to protect his property (likely a combination of livestock and tools), Smith retrieved a double barrel shotgun and shot one soldier in the heart, killing him instantly. The remaining soldiers seized Smith, bound his feet and limbs with rope, and tied him to a horse. His daughters begged and pleaded for their father’s life, but the soldiers forbade them to say goodbye and warned them to stay back. The cavalrymen dragged Smith an estimated four miles to the back of the Mathews County Courthouse, where they denied him both food and water. Eventually, the soldiers bound Smith’s hands behind his back, wrapped a rope around his neck, and attempted to hang him. The rope, however, was ineptly tied, and Smith dropped to the ground still alive. Soldiers responded by shooting him five times. They buried him face down with his feet sticking out from the dirt and labeled him a “bushwhacker,” or guerrilla fighter. Lizzie lost her mother and two brothers in 1886, and she remained single for the rest of her life.

span of one year left Lizzie in mourning for years to come. The loss of her uncle, Sands Smith II, was particularly noteworthy and traumatic. On October 7, 1863, Smith encountered several Union soldiers belonging to the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Attempting to protect his property (likely a combination of livestock and tools), Smith retrieved a double barrel shotgun and shot one soldier in the heart, killing him instantly. The remaining soldiers seized Smith, bound his feet and limbs with rope, and tied him to a horse. His daughters begged and pleaded for their father’s life, but the soldiers forbade them to say goodbye and warned them to stay back. The cavalrymen dragged Smith an estimated four miles to the back of the Mathews County Courthouse, where they denied him both food and water. Eventually, the soldiers bound Smith’s hands behind his back, wrapped a rope around his neck, and attempted to hang him. The rope, however, was ineptly tied, and Smith dropped to the ground still alive. Soldiers responded by shooting him five times. They buried him face down with his feet sticking out from the dirt and labeled him a “bushwhacker,” or guerrilla fighter. Lizzie lost her mother and two brothers in 1886, and she remained single for the rest of her life.

Tennessee remembers Jonathan Waverly Bachman as the “Pastor of Chattanooga” not just for his sermons, but also for his relentless acts of service and charity. Bachman served as a chaplain in the Confederate army. In 1878, a yellow fever epidemic struck Chattanooga. Bachman sent his family to his brother’s house for safety, remaining behind to minister and nurse his sick friends and neighbors. He grew vegetables to distribute to the sick and allowed passersby to drink from his freshwater well. Every morning during the epidemic, he gathered neighbors to read verses from Psalm 91: “Surely He shalt deliver thee from the snare of the fowler and from the noisome pestilence. / Thou shalt not be afraid for the terrors by night: for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that walketh noonday.” Bachman reportedly ministered to yellow fever patients regardless of their ethnicity or economic status. As a local writer later reported, “he never hesitated to go to sick patients of every race and color, and he nursed them himself.” He served Chattanooga for more than 50 years.

chaplain in the Confederate army. In 1878, a yellow fever epidemic struck Chattanooga. Bachman sent his family to his brother’s house for safety, remaining behind to minister and nurse his sick friends and neighbors. He grew vegetables to distribute to the sick and allowed passersby to drink from his freshwater well. Every morning during the epidemic, he gathered neighbors to read verses from Psalm 91: “Surely He shalt deliver thee from the snare of the fowler and from the noisome pestilence. / Thou shalt not be afraid for the terrors by night: for the pestilence that walketh in darkness; nor for the destruction that walketh noonday.” Bachman reportedly ministered to yellow fever patients regardless of their ethnicity or economic status. As a local writer later reported, “he never hesitated to go to sick patients of every race and color, and he nursed them himself.” He served Chattanooga for more than 50 years.

Writing about the people of the Confederacy drastically changed my conceptions of the Civil War. It challenged my assumptions about the individuals who fought, as many did not own slaves and enlisted out of sheer defense and preservation. It pushed me to consider the ways in which the legacy of the Confederacy lives on in our own geographical, political, and social borders today. This work led me to face an obvious yet confounding reality: the people of the Confederacy were complex individuals and capable of good things. Juggling the paradoxical relationship between this fact and the motivations of antebellum politics has certainly helped me to grow as a historian.

As I began to research and write about these artifacts, my connection to the ACWM deepened. I paid closer attention to the layout of each display case and noted how it portrayed a chronological narrative. I interacted with visitors, answered their questions, and devised strategies for enhancing the museum experience. Chris introduced Yash and me to John Falk’s research on visitor motivation, and he asked us to consider all types of guests. We were trusted to critique plans for future exhibits, and we even created new interactives aimed to illuminate the Underground Railroad and the antislavery movement. I look forward to visiting the museum in the future, as my research and writing will be included in its upcoming mobile guide, and my influence will be visible in the 2024 “Impending Crisis” installation.

I am so grateful to both the American Civil War Museum and the Nau Center for the chance to explore my passion for both history and the written word. As a recent UVA graduate, I have deeply valued the trust placed in me to conduct impactful research and provide input in a professional setting. Though my future has yet to be charted, I feel a new sense of confidence in my work ability, preparedness, and passion to pursue meaningful historical stories wherever life takes me.