The Black Lawmen of Reconstruction

by J. Jacob Calhoun | | Tuesday, June 13, 2023 - 17:06

On November 9, 1870, at the height of Congressional Reconstruction, two Black lawmen marched at the head of a column of freedpeople in Donalsonville, Louisiana, in an effort to protect their newly won citizenship rights. They had mustered in a veritable battalion of formerly enslaved sugar workers to recover ballot boxes stolen by a coalition of white Democrats and conservatives and stashed in the Ascension Parish courthouse. Populated by more than a thousand freedpeople, this de facto militia marched on the courthouse, routed the white insurgents, and recovered their votes.[1]

The leaders of this march, David Fisher and Joseph C. Oliver, served as constable and sheriff respectively, and were two of the thousands of Black Americans that ascended to local offices during the height of Reconstruction efforts in the states of the former Confederacy. Though the actions of Black state and federal congressmen defined much of what made Reconstruction a period of hope for many Black Americans, perhaps even more important to freedpeople was Black Americans’ entrance into law enforcement.

Throughout the antebellum period, police forces in the South had terrorized Black people and buttressed the institution of slavery. Often, these police forces took the form of localized white militias, which performed a wide range of functions within their local communities, including surveillance of the enslaved. These antebellum militias enforced curfews and arrested accused lawbreakers, but they also hunted freedom seekers they deemed “fugitives” and patrolled the roads to discourage flight. In doing so, these local police forces established the antebellum South’s white supremacist vision of “law and order.” Moreover, local police forces proved incredibly hostile to Black Americans in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. With Black Americans’ citizenship status still suspect in 1866, white policemen of the South either ignored violent acts perpetrated by white southerners against Black women, men, and children or actively participated in such atrocities themselves.

The infamous New Orleans “Riot” of 1866, more aptly termed the New Orleans Massacre of 1866, demonstrated the hostility of the police toward the newly emancipated. On July 30, 1866, white policemen led a brutal attack against a group of Black veterans demonstrating in front of the Mechanics Institute in New Orleans, and in this melee, policemen perpetrated some of the most heinous acts. According to one witness, they “saw policemen shoot two negroes dead, who had been knocked down by rocks.” Not only did this event convey to Northern Republicans the need for far more expansive protections for Black Americans, but it also illustrated the deep need for Black Americans to have some measure of control over the police force. Congressional Reconstruction offered Black Americans an opportunity to wring control of the local police forces from those that despised them and bring about a form of “law and order” that actually protected Black Americans’ rights and dignity.[2]

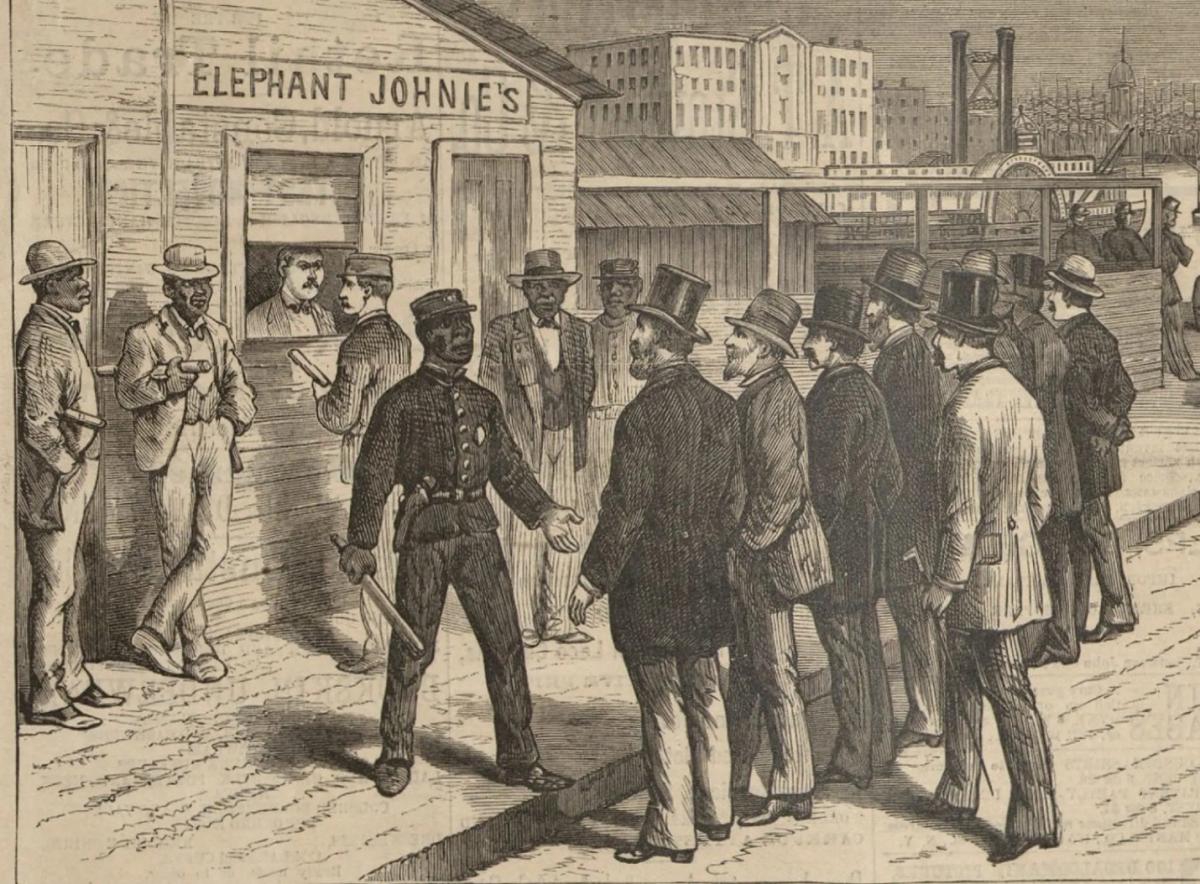

In Louisiana, Black men labored at all levels of law enforcement during Reconstruction. Many served as rank-and-file policemen within the Metropolitan Police Force, a newly reconstituted, multiracial police force in New Orleans under the direction of former Union colonel Algernon Sidney Badger. Upon their initial mustering in, however, the force found itself woefully unequipped to deal with the widespread mob violence that erupted. During the bloody chaos of the 1868 presidential election in Louisiana, for instance, the Metropolitan Police Force could not maintain a presence on the streets and, due to lack of numbers and arms, was forced to surrender its city to a Democratic mob that killed hundreds of Black Louisianans in New Orleans alone. The Metropolitan Police found its footing by 1869, however, and the new multiracial force worked in tandem with the newly established state militia, commanded by former Confederate general James Longstreet, to both preserve law and order and defend Black Americans’ citizenship rights in New Orleans. To this end, the Metropolitan Police Force met with a degree of success as Black lawmen worked alongside white colleagues, some of whom were ex-Confederates, to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments and protect the citizenry of New Orleans from white Democratic terrorists that had plagued it up to that point. Though chaos certainly pervaded the city throughout all of Reconstruction and racial violence was commonplace, between 1870 and 1874, the Metropolitans managed to prevent murders, assaults, and “outrages” from reaching the heights they had during 1868.[3]

The majority of Black Louisianans, however, did not live in or near New Orleans and therefore benefited neither from the protection of the Metropolitan Police Force nor the state militia. Black people in rural communities instead fought to ensure that local constabularies and sheriff’s offices were populated by Black men or their white Republican allies. Enfranchisement under Louisiana’s 1867 Constitution meant that Black men could vote for local Parish Sheriff and, in turn, meant that they could elect a Black candidate to such a position. In those parishes where white intimidation and violence became so great as to prevent Black Louisianans from voting for the candidates they wished, Governor Henry Clay Warmoth bypassed the electoral process and personally appointed Republicans as constables and sheriffs. Significantly, sheriffs had the capacity to appoint deputies according to their discretion, and Black sheriffs often prioritized appointing other Black men in order to ensure their deputies’ commitment to racial equality and the preservation of Democracy in the Reconstruction South. In Warren County, Mississippi, for instance, Black leader Thomas J. Cardozo explicitly promised to employ solely Black men as his deputies, and similarly in Louisiana, Black sheriffs during Reconstruction appointed Black and Republican deputies almost exclusively.[4]

From the Feliciana Parishes in the southern reaches of the state to Morehouse Parish on the border to Arkansas, Black Louisianans could be found occupying sheriff’s offices as well as serving as parish judges and clerks throughout the early 1870s. For example, Sheriff Henry Smith, Constable George Swayze, and Judge Dewing, all Black Louisianans, served contemporaneously in East Feliciana Parish, and by all accounts, performed admirably in their duties. George Swayze in particular took an aggressive, yet tempered, approach toward those that took issue with his occupation as a lawman. Threatened with death multiple times by white residents of his parish, Swayze refused to abandon his hometown of Bayou Sara. On one occasion, he witnessed a visitor to his local tavern strike a Black man with a pistol butt for having a drink with a white man. Swayze readily confronted the white assailant. In fact, he was so angered by the bigoted act that three friends had to restrain him to prevent him from attacking the armed assailant bare-handed. When the same assailant arrived with a posse the next day to kill Swayze in the streets of Bayou Sara, Swayze fought off the armed men with just a hickory stick, knocking his would-be assassin from his horse and beating him into a surrender. Such a public stand against terrorism forced Swayze to flee to New Orleans for a few weeks, but surprisingly, when the assailant requested a “friendly” meeting with Swayze, the constable accepted. Despite Swayze’s abhorrence of injustice, he also maintained a vested interest in preserving law and order and demonstrated amazing restraint. According to Swayze, the two men “met and talked it over and we made friends.” Though circumstances limited Swayze’s options, his acceptance of an olive branch from a man who publicly tried to kill him demonstrates his deep commitment to his duties.[5]

For Black lawmen, combating white supremacy and establishing peace in the postemancipation South were not discrete goals. Louisiana during Reconstruction suffered from widespread tumult, but the perpetrators of this chaos must remain in full view to gain an accurate picture of the period. White terrorists engaged in deplorable acts of violence to reestablish white supremacy of as the bedrock of Southern society, and such violence served two purposes. Brutality directed against Black citizens not only limited the exercise of their rights, whether to the franchise or otherwise, but it also eroded Northern white support for the federal Reconstruction project. The actions of terrorist organizations such as the Knights of the White Camelia, the Seymour Knights, and most notably, the Ku Klux Klan, broadcast the idea that the multiracial Reconstructed state governments of the South were unable to keep order and should, perhaps, be surrendered back to southern Democratic control. These cells of white supremacists aimed to cause chaos in part so they could point to the chaos they had wrought and blame it on Black Americans and the Republican Party. For instance, in Clinton, Louisiana, Democrats participated in a widespread campaign of hog-stealing and arson while Democrat newspapers blamed Sheriff Henry Smith for being unable to maintain order. In such circumstances, publicly combating violent white supremacists, as Swayze, Fisher, Oliver, and countless others had done, served to both secure freedpeople’s rights as guaranteed by the Reconstruction Amendments and also take strides toward the preservation of law and order and the survival of Reconstruction.[6]

Unfortunately, Black lawmen were often outmanned and nearly always outgunned by white terrorists, particularly after 1874 and the inauguration of the first “Mississippi Plan,” a targeted campaign of violence by the Democratic Party aimed at completely disfranchising Black southerners. In Louisiana, Democrats formed “rifle companies” and purchased high-end, repeating firearms en masse. Black sheriffs and constables, often armed with little more than a revolver or perhaps an Enfield rifle they were able to hold onto after their service in the United States Colored Troops, were unable to combat such heavily armed units of terrorists. Black lawmen of all stripes were prime targets of such violence. David Fisher, after leading the march at Donaldsonville, was gunned down by members of the “White League” at the infamous Battle of Canal Street in New Orleans in 1874, a death knell for the Metropolitan Police Force and the state militia. Sheriff Henry Smith of East Feliciana Parish was shot in the hip and run out of town along with Judge Dewing. Across the state, Black Americans were forced out their positions as lawmen not by the will of the voters but by force at the hands of violent Democratic mobs.[7]

Author: John J. Calhoun is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia. He is originally from Alabama and received his B.A. from Loyola University New Orleans. He received his M.A. from the University of Maryland where he undertook a thesis project that explored how early emancipation in the sugar parishes of Louisiana shaped the ensuing political contests in the region.

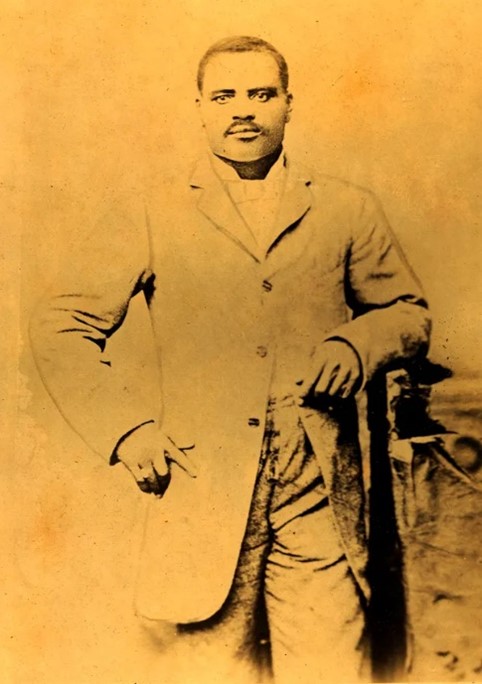

Images: (1) Washington Lyons, Sheriff of Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, 1872-1876, Ellender Memorial Library Archives, Nicholls State University; (2) Black Policeman Addressing Crowd During Reconstruction, Louisiana Research Collection, Tulane University

[1] "Latest from Donaldsonville," New Orleans Republican, Nov. 11, 1870; James D. Wilson, Jr.,"The Donaldsonville Incident of 1870: A Study of Local Party Dissension and Republican Infighting in Reconstruction Louisiana," Louisiana History 38, vo. 3 (1997): 329-345; Stuart Rockoff, “Carpetbaggers, Jacklegs, and Bolting Republicans: Jews in Reconstruction Politics in Ascension Parish, Louisiana,” American Jewish History 97, no. 1 (2013): 39-64.

[2] Carol Anderson, The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021); Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); Stephanie McCurry, Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

[3] Justin A. Nystrom, New Orleans after the Civil War: Race, Politics, and a New Birth of Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010); John C. Rodrigue, Reconstruction in the Cane Fields: From Slavery to Free Labor in Louisiana's Sugar Parishes, 1862-1880 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2001), Otis A. Singletary, Negro Militia and Reconstruction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1957); Joe Gray Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877, Ted Tunnell, Crucible of Reconstruction: War, Radicalism, and Race in Louisiana, 1862-1877 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992); Henry Clay Warmoth, War, Politics, and Reconstruction: Stormy Days in Louisiana, Southern Classics Series, (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006).

[4] Adam Fairclough, “Alfred Raford Blunt and the Reconstruction Struggle in Natchitoches, 1866-1879,” Louisiana History 51, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 284-305; Christopher Waldrep, “Black Political Leadership: Warren County, Mississippi,” in Local Matters: Race, Crime and Justice in Nineteenth Century South eds. Christopher Waldrep and Donald G. Nieman (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001).

[5] “Testimony of George Swayze,” 45th U. S. Congress, 2nd Session, Presidential Election Investigation. Vol. 3 (New Orleans, LA, 1878), 391-397; “Testimony of George A. J. Swayze,” 44th U. S. Congress, 2nd Session, Message from the President of the United States, transmitting. A Letter, Accompanied by Testimony, Addressed to Him by Hon. John Sherman and Others, in Relation to the Canvass of the Vote for Electors in the State of Louisiana (New Orleans, LA, 1876), 189-190.

[6] Leanna Keith, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & the Death of Reconstruction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984); Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); Lou Falkner Williams, The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials, 1871-1872 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1996).

[7] James D. Wilson, Jr., "The Donaldsonville Incident of 1870: A Study of Local Party Dissension and Republican Infighting in Reconstruction Louisiana," Louisiana History 38, vo. 3 (1997): 329-345; “Testimony of Henry Smith,” Message from the President, 231-235; “More War Rumors,” The Times-Democrat, October 9, 1875; New Orleans Bulletin, October 12, 1875; “East Feliciana,” The Times-Picayune, October 15, 1875; “The White Line Disorders,” New Orleans Republican, October 16, 1875.