Crispus Attucks’s Civil War Service

by Jonathan Lande | | Thursday, February 23, 2023 - 17:21

On March 5, 1863, a contingent of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry gathered with prominent abolitionists at Tremont Temple in Boston to celebrate Black heroism. President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had opened the door to the enlistment of African Americans just two months prior, but the festivities did not center on Black Union soldiers. Celebrants instead praised the nation’s first martyr—Crispus Attucks—because they thought that recollections of Black valor on the nation’s altar were integral to the same battles being waged by Black soldiers around the war-torn Confederacy.

By the outbreak of the Civil War, many Americans understood that Attucks was the first to perish during the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. As the war over the Union raged, those at Tremont Temple feted the martyr of the American Revolution with speeches and patriotic pomp. Black celebrants had used other holidays, including Emancipation Day and July Fourth, to make political statements regarding abolition and civic inclusion. In a similar vein, they turned Crispus Attucks Day into a chance to make the country understand that African Americans were as American as any other group and that they deserved rights. Described in The Liberator on March 20, the celebration was adorned by historical documents, such as a 1750 advertisement calling for the return of Attucks to his enslaver, the Boston Gazette’s 1770 account of the massacre, and a certificate of honorable discharge of a Black soldier by George Washington. The meaning of the documents was plain: the celebrants nurtured a civic memory of African Americans’ patriotism and drive for liberation.

When the festivities commenced, a quartette sang, “Oppression shall not always reign,” before William Cooper Nell rose to speak. Nell, who had penned two histories of the Revolution, extolled Attucks. In previous celebrations, including a celebration less than a month before the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Nell had cited the martyr’s contributions and demanded recognition for his sacrifice. He continued this strain in 1863. “Ninety-three years ago this evening,” he opined, “Crispus Attucks immortalized himself by rallying a company of patriots … and leading them on against the British forces, in which encounter he received two musket balls, one in each breast, and fell—himself the first martyr on that day ‘which history has selected as the dawn of the American Revolution.’” But to the usual repertoire, Nell chose to couch the holiday fully in the wartime moment.

He connected the service of Black men in the Civil War to Attucks, alluding to pervasive concerns regarding Black men’s courage and commitment to Union. “This historic event is invested with special significance this day and hour, when the question is asked on every side, is the colored man patriotic? will he fight?” To this, Nell declared: “The page of impartial history triumphantly answers the question of his patriotism and bravery,” and listed the men’s contributions at Lexington, Bunker Hill, the War of 1812, and in the Civil War, noting the brazen escape of Robert Smalls from enslavers in 1862. Here, Nell squarely established Black men as bold, loyal soldiers of the nation. Yet he did not stop drawing the connection. Before closing, he shifted from remembrance to full-throated support for the enlistment of African Americans, pointing to the value of military service to racial uplift.

“I hail the formation of the Massachusetts 54th (colored) Regiment,” he began, “and welcome it as a most auspicious sign of the times; for although some colored citizens have manifested anxiety as to whether their status as equals under the law would be advanced thereby, my conviction has been from the first, and is now very strong, that by accepting the opportunity of becoming soldiers in this our nation’s trial hour, the result cannot be otherwise than a full acknowledgment of every right; and if the 54th Regiment will but fulfill the hopes and expectations of their friends, (among whom I am proud to proclaim myself one,) they will materially aid in the conquest of Southern rebels, and thereby so conquer Northern prejudice, that on their return from the field of victory, they may march up State street over the spot consecrated by the martyrdom of Crispus Attucks, amid the plaudits of admiring citizens.” With this, Nell made patently clear the link between patriotism, soldiering, and rights, a theme that he had been cultivating for decades and repurposed during America’s bloody internecine strife.

Indeed, while many gathered in 1863 (and today, Americans know of Attucks to varying degrees), the emergence of Attucks as a martyr was neither assured nor accidental. In the 1840s, few Black or white Americans recalled Attucks. To correct the amnesiac public, Nell had spent two decades reminding Americans of Attucks in newspaper accounts, speeches, and historical monographs. Nell’s mission was no idle antiquarianism. The abolitionist historian, like fellow Black intellectuals, had dedicated great time and energy to rehashing America’s past to procure the access of Black men and women to democracy, as Stephen G. Hall and Stephen Kantrowitz show. For Nell, as for many nineteenth-century Black historians and activists, rewriting the nation’s preceding years was a crucial element in the ongoing fight for African Americans’ liberation. Nell made Attucks the tip of the spear in this melee of memory, Mitch Kachun demonstrates, and in doing so, Nell helped usher the original patriot into the American pantheon. By 1848, abolitionists in Boston not only remembered the martyr but celebrated him on Attucks Day . During the Civil War and its aftermath, Nell’s activism would have a profound influence on the enlistment of men, the histories of their service that would follow, and the struggle for Black citizenship.

As I have argued in my article, “The Black Badge of Courage,” Nell emphasized military martyrdom because he saw it as the “passport to honorable and lasting recognition.” In other words, the link between military service, sacrifice, and citizenship existed but was nascent before the 1830s. As Mark S. Schantz reveals, a movement among Americans entrenched a commitment to military service as the sine qua non of citizenship in the three decades proceeding the war. Nell participated in this movement, pushing for the recognition of Black heroism. This tactic of racial uplift, in turn, came to play a pivotal role in shaping how Black leaders appreciated the war and why they pushed so hard for the enlistment of Black men.

Leaders thought military service would be a gateway to freedom and inclusion. While Black men performed a host of empowering acts, ranging from quietly laboring to caring for family, military service became fundamental to strategies for attaining rights. As the world-renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass proclaimed, “Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letter, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny he has earned the right to citizenship.” The fight for recognition would not be confined to the fields of battle, however.

The fight Nell began in the pages of history would continue in the opening years of Reconstruction. Black historians William Wells Brown and Frances Rollin built on Nell’s historical writing and activism. Many Americans looked to memory because, as Caroline Janney writes, “memory is not a passive act.” It is, as it was in the 1860s, active creation. Black leaders engaged in the fight over how the war would be remembered, too. They crafted what David Blight calls the emancipationist vision of the war. Brown and Rollin joined this activism, yet they chose to write of Black men’s valor in hopes of preserving their sacrifices and securing a place in the body politic. Brown, a formerly enslaved man turned venerable abolitionist and author, indelibly connected Black soldiers’ actions during the war to their redoubtable patriotic fervor. Rollin was a free-born South Carolina woman who had joined the war as an educator for freedpeople before contributing her able pen to the battle of the inkwell. In her biography of Major Martin R. Delany (104th US Colored Infantry), she answered burgeoning anti-Black racism to help secure suffrage. These histories cast Black Union soldiers as undeniable heroes of the war who, for their sacrifices, deserved citizenship and the vote. Brown and Rollin would not be the last to scribe heroic accounts of Black soldiers’ role in Union victory.

This “Black Badge of Courage” served as an indispensable tool for generations to come. As Barbara Gannon and Elizabeth Varon reveal, veterans George Washington Williams and Joseph T. Wilson would lend their voices to the struggle. Thus, with his histories, Nell had inaugurated a militaristic strain of Black historical writing and had made the possibility for the writing of war histories to serve much broader efforts than factual accuracy. For the Black Civil War historians, as it was for Nell, the struggle to secure liberty and rights was a fight that demanded the sword—and the pen.

Author: Jonathan Lande earned his Ph.D. at Brown University (2018) and is an assistant professor of history at Purdue University. Before joining Purdue, he was the Schwartz Postdoctoral Fellow at the New-York Historical Society and the Brown-Tougaloo Exchange Faculty Fellow. He is the recipient of the Allan Nevins Dissertation Prize and Cromwell Dissertation Prize. He has published articles in the Journal of American History, Journal of American Ethnic History, Journal of Social History, Journal of African American History, Civil War History, and The Washington Post. He is currently completing a book examining Black deserters and mutineers during the Civil War, which is under contract with Oxford University Press.

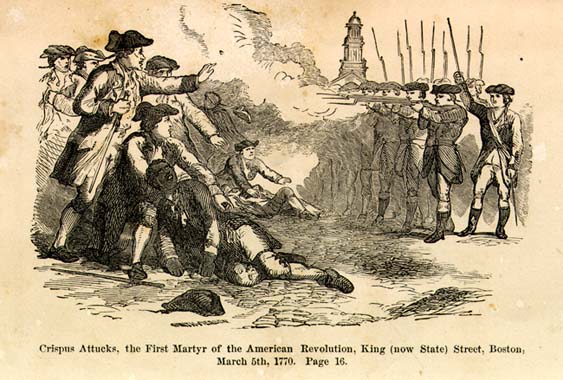

Images: (1) "Crispus Attucks, the First Martyr of the American Revolution, King (now State) Street, Boston, March 5th, 1770," from William Cooper Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (Boston, MA: Robert F. Wallcut, 1855); (2) William Cooper Nell, available from Wikipedia Commons.