Drumming Youths: The Practical and Symbolic Value of Drummer Boys to the Union Cause

by Neil Salazar | | Thursday, January 19, 2023 - 16:46

Because of their crucial role in the ranks and their symbolic value to the home front, Union drummer boys were essential to maintaining the northern war effort. These twelve to seventeen year-old boys served the Union in two major ways: practically and symbolically. Field drummers operated as one of the principal mechanisms for communication in camp, on the march, and on the battlefield. Although this role may seem obvious, their responsibilities were hardly confined to beating a drum. Drummers participated in a range of duties. From standing guard through the night to carrying stretchers and ditching their sticks for rifles, drummer boys molded themselves into whatever shape the Union required of them. Faced with terrifying threats in faraway lands, drummer boys often improved morale for their comrades when no one else could. Whether this was done actively by tapping out an enjoyable beat or passively by being the subject of a cruel joke, drummer boys were aware of their practical importance.

While these boys enlivened their fellow soldiers, northern newspapers sought to bring a sense of heightened morale and resolve to the home front by framing drummer boys as heroes and martyrs. To do so, writers and correspondents pinned Union drummers on a spectrum of masculinity that ranged from childhood innocence to the apex of patriotic manliness, regardless of how they saw themselves. Although there was no strict formula, childhood innocence was most often accentuated if the boy had died, illuminating the barbarism of the enemy and the determined nature of the boy. On the other hand, patriotic manliness would emanate off the page if the boy had accomplished a heroic feat worthy of celebration. It is evident that the military service began to mold each drummer into a man, but only the patriotic heroes were ever nationally recognized as ideal representations of masculinity.

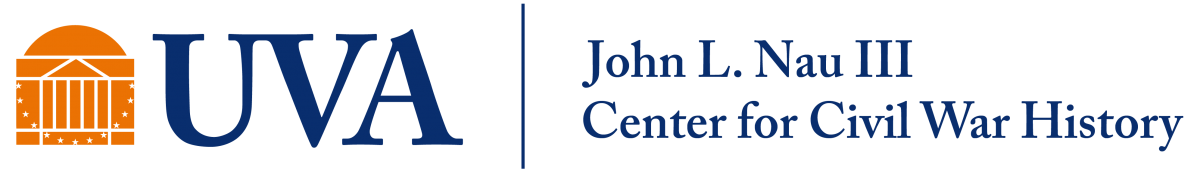

To understand the layered symbolic importance of drummer boys, it is necessary to first learn what exactly a drummer boy was and the practical value that they added to the Union army. First of all, drummer boys were officially entitled “field musicians”-- a term which included both fifers and drummers. Field musicians were assigned two to a company in Federal infantry regiments, so a fully-manned regiment possessed ten drummers and ten fifers. Together, these twenty field musicians formed a drum corps which was led by a drum major. The drum corps differed greatly from regimental army bands in instrumentation, role, and numbers. Bands were typically raised from established town or militia bands, which possessed horns in addition to woodwinds and percussion. On the other hand, drum corps were filled by boys and men on an individual basis and were not organized groups prior to enlistment. Drummers in the corps almost exclusively played snare drums, while band drummers performed with snares, bass drums, and even cymbals. The Federal government supplied most field drummers with their instruments; however, the government sourced those drums from private manufacturers, who were not required to craft snares in a uniform or even similar manner. This resulted in a wide variety of percussive timbres that would have been heard in camp and on the battlefield, making individual drummers audibly distinguishable from their comrades.[1]

In terms of age, most field drummers were actually young boys and teenagers, ranging from twelve to seventeen years of age. Many of these young boys deeply desired to enter the ranks along with their elder family members and friends, but due to their age the only avenue to the battlefield was the drum (or fife). In consequence, newly recruited drummer boys were rarely qualified percussionists, and recruiters seemed more interested in filling quotas than hosting auditions, which were technically required by federal law. Once these volunteer drummers formed with their company in training camp, there was rarely a trained instructor knowledgeable enough in the percussive arts to adequately train them. Drum majors, as non-commissioned officers, were assigned the responsibility of training both fifers and drummers; however, they were typically more informed on the basics of pitched instruments than the rudiments of drumming. In contrast, Regular Army field drummers were rigorously trained at the aptly named School of Practice in New York City. These boys endured months of constant training and drill, practicing and mastering thirty-six rudiments from dawn to dusk each day. In contrast, a volunteer drummer might have heard his first long roll or paradiddle months into his enlistment.[2] Rote memory was the means by which the majority of drummer boys learned vital signals such as the reveille and breakfast call, making the minority of trained percussionists essential resources for not just ignorant drummer boys, but the entire army.[3]

Whether on the battlefield, in camp, or on the march, field drummers were necessary to sustain unit morale and communicate orders. From waking up, to eating, to battlefield tactics, soldiers and officers depended on the signals of drummer boys for the successful completion of nearly every action they undertook or ordered. For instance, every night, one drummer from the corps would stay awake so that he could tap out the reveille come morning, waking up his entire regiment. While incompetent drummers could easily annoy and even antagonize their armed comrades, well-trained boys could provide immense entertainment and morale for the men of their regiment and even inspire them to keep fighting. It was often these skilled drummers who caught the attention of northern newspapers, for they were so popular within their regiments. In other instances, drummer boys garnered popularity for their actions rather than their playing ability.[4]

Throughout the Civil War, newspapers across the loyal North projected iconic representations of drummer boys into Union homes. Although the creators of newspapers and popular literature often portrayed men of fighting age as symbols of patriotism, Christianity, and closure, grown men proved to be less emotionally potent and literarily malleable than the drumming youth. Due to their ambiguous status as combatants and men, drummer boys could easily be shaped into whatever symbol the paper thought would best appeal to its readers. The most obvious and inspiring of these symbols was that of the hero.[5]

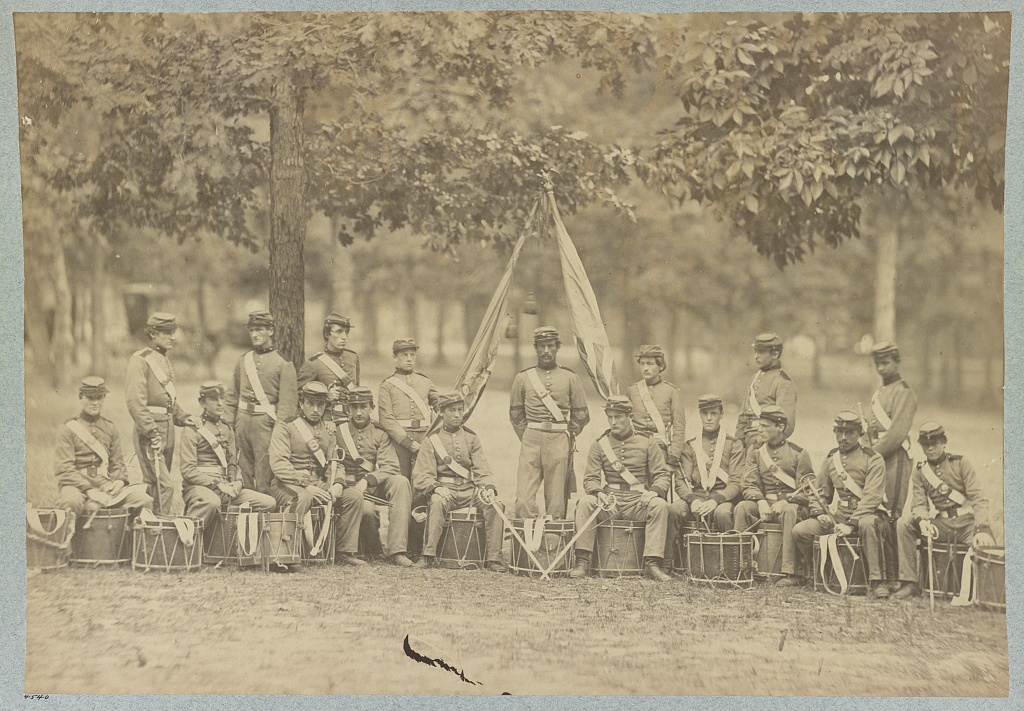

One of the most prominent of these young heroes was a boy by the name of Robert Henry Hendershot. Fatherless, Robert was raised by his mother, Deborah, in the depths of poverty, sharpening his determination in the face of adversity. By the summer of 1862, Robert found himself marching under the beating Tennessee sun, bound for Chattanooga. He had enlisted earlier that year at the green age of thirteen as the field drummer for Company B of the 9th Michigan Infantry. In pursuit of the Confederate colonel John Hunt Morgan, the 9th raced eastward across Tennessee under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Thomas T. Crittenden. Poor logistical planning, however, left the 9th detached from the rest of its brigade. On the morning of July 13, 1862, Confederate colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest rode out with his cavalrymen and attacked Robert’s vulnerable position, initiating the First Battle of Murfreesboro. Col. William Duffield, the 9th’s ranking officer, was wounded and taken off the battlefield early in the day, devastating the morale of Robert’s comrades. To make things worse, Robert’s regiment was not relieved or reinforced for the duration of the battle. By dusk, Robert had weathered his first lick of combat, but he along with the majority of the 9th Michigan had been captured.[6]

One of the most prominent of these young heroes was a boy by the name of Robert Henry Hendershot. Fatherless, Robert was raised by his mother, Deborah, in the depths of poverty, sharpening his determination in the face of adversity. By the summer of 1862, Robert found himself marching under the beating Tennessee sun, bound for Chattanooga. He had enlisted earlier that year at the green age of thirteen as the field drummer for Company B of the 9th Michigan Infantry. In pursuit of the Confederate colonel John Hunt Morgan, the 9th raced eastward across Tennessee under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Thomas T. Crittenden. Poor logistical planning, however, left the 9th detached from the rest of its brigade. On the morning of July 13, 1862, Confederate colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest rode out with his cavalrymen and attacked Robert’s vulnerable position, initiating the First Battle of Murfreesboro. Col. William Duffield, the 9th’s ranking officer, was wounded and taken off the battlefield early in the day, devastating the morale of Robert’s comrades. To make things worse, Robert’s regiment was not relieved or reinforced for the duration of the battle. By dusk, Robert had weathered his first lick of combat, but he along with the majority of the 9th Michigan had been captured.[6]

After being paroled, Robert was sent to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio, where he made it clear that the combat of July 13 and his subsequent imprisonment had not deterred his passion for Union. While the poor financial status of his mother probably spurred the boy to keep serving for the pay, it is evident that Robert was dedicated to the North’s cause. For example, while in Columbus, Robert helped to encourage enlistments by attending public events. Civil War music historian Kenneth Olson dedicated an entire chapter to the recruiting power of regimental bands, arguing that they were successful in attracting enlistments because their sound instilled patriotism in potential recruits. Assuredly, Robert thought that drummer boys also had a role to play in Union recruitment. Although regimental bands certainly participated in more recruiting efforts, the sight of a young fourteen-year-old drumming his heart out for his country appealed not only to other men’s patriotism but also to their perceptions of manhood. If little Robert Hendershot could brave the heat of battle and the uncertainty of Rebel captivity, then local Ohioans twice his age should have had no reason to cower at home, that is, if they were real men.[7]

Despite suffering a series of “epileptic fits” that saw him discharged from the service, Robert snuck his way back to the drum and guns by enlisting in the 8th Michigan Infantry. Three months later, the drummer white knuckled his snare on the banks of the Rappahannock River, staring out at the Confederate city of Fredericksburg as winter settled into Virginia. Work on pontoon bridges had ceased due to increased pressure from rebel marksmen; men from the 8th Michigan volunteered to eliminate the sharpshooters, but Robert was excluded from the strike force due to his age. Regardless, Hendershot sneaked onto one of their boats by hanging off the side after he pushed his comrades offshore. Once his fellow soldiers had noticed his presence, Robert reportedly shouted: “I wish to go, and if I die, it will be for my country.” Upon landing in enemy territory, Robert’s unit came under fire so heavy that it blew Hendershot’s snare drum “to atoms.” Luckily, the now drum-less boy had avoided the same fate and was able to push towards the snipers in search of recompense for his disintegrated instrument. Hendershot went on to arm himself with an unattended rifle with which he captured a piece of the rebel flag, an old clock, and a wounded rebel.[8]

Although the battle of Fredericksburg resulted in an atrocious military blunder for the Union, Robert Hendershot emerged as a hero of the Army of the Potomac. After returning to camp with his Confederate prisoner, tales of Robert’s heroic feats spread throughout the defeated and demoralized ranks. Before long, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside came to congratulate his most accomplished drummer, stating “Boy, I glory in your spunk. If you keep on in that way, you will be in my place before many years.” Robert had earned the respect of Burnside by virtue of his courage, but that respect was still between a man and a youth, requiring Robert to continually prove his bravery to one day earn the rank of man.[9]

According to historian Joseph F. Kett, an expert on notions of youth in nineteenth-century America, the period now known as adolescence was a time when maturing children, or “youths,” were vulnerable to ideological molding. A vast number of Yankee soldiers would have been considered youths, as the category extended from one’s middle teen years to one’s mid-twenties. Fighting youths were often stamped as men if they enlisted in the rank and file; however, field musicians of the same age experienced the Union army as an institution that would prepare them for manhood, rather than outright pronouncing them as men. Even after Robert exchanged his drum for a rifle during the battle of Fredericksburg, he was still denied the title of man by Burnside and the newspapers that catapulted him into national fame.[10]

On a crisp Saturday morning in late December 1862, The Detroit Free Press started its paper off with the story of Robert Henry Hendershot, a local boy turned war hero. Hendershot had returned to his home-city of Detroit on that Friday, and the Press wasted no time in gathering his account. Robert had wanted to stay with his regiment, but surgeons noticed a bout of his epilepsy and discharged him from the service for a second time. News of his heroism was spreading rapidly, elevating his name to a level of recognition that prevented him from signing on with another regiment. The Republican-leaning Press saw Hendershot as a leading symbol of patriotic courage that could better serve the Union cause in print than on campaign. The Press strung together his account of Fredericksburg with a splattering of interjections that painted Robert as a humble youth determined to serve the Union as he aspired to attain manhood and soldierdom.[11]

Despite Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s mounting victories in the western theater, Union morale and manpower were sharply declining in the East. To uplift popular morale and spur enlistments, Unionist newspapers throughout the country began reprinting the Press’ rendition of Hendershot’s heroic symbolism. By the spring of 1863, the famous poet George W. Bungay had written a lively poem about Hendershot’s bravery, equating his drum beat to the passion for Union and bravery in the face of terrible combat. In exchange for his service, the New-York Tribune gifted the boy a brand-new snare drum with a glistening silver shell, rosewood rims, and clear drum heads. Robert Henry Hendershot quickly became a household name and although his actions did not inspire enough enlistments to prevent the Conscription Acts of 1863, his story certainly dashed an ounce of morale into a nation reeling from the Peninsula Campaign.[12]

Author: Neil Salazar is an undergraduate research assistant at the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History.

This blog post is a shortened version of a research paper Neil Salazar wrote in Professor Elizabeth R. Varon's "Gender History of the Civil War Era" seminar in the fall of 2022.

Images: (1) "Drum Corps, 8th New York State Militia, Arlington, Va., June, 1861," LOT 4190-E, no. 24 [P&P], available from Library of Congress; (2) Robert Henry Hendershot, available from Wikicommons

[1] Robert Garofalo and Mark Elrod, Of Civil War Era Musical Instruments and Military Bands (Charleston, WV: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1985), 35-36.

[2] The long roll is a drum rudiment that is essential to developing the technical ability necessary to perform nearly any piece composed for the snare drum. The long roll consists of two right-handed strokes (RR) followed by two left-handed strokes (LL), repeating that pattern through a period of acceleration followed by one of deceleration. The paradiddle is another essential rudiment that is practiced with the same tempo fluctuations as the long roll. However, the pattern differs in that the first two strokes alternate hands (RL) while the second set originate from the same hand as the leading stroke (RR). This is followed by the inverse pattern (LRLL), making the paradiddle a repetition of RLRR LRLL.

[3] Garofalo and Elrod, Of Civil War Era Musical Instruments and Military Bands, 35-36; Kenneth E. Olson, Music and Musket: Bands and Bandsmen of the American Civil War (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1981), 85-87.

[4] Olson, Music and Musket, 85-87.

[5] Alice Fahs, The Imagined Civil War: Popular Literature of the North and South, 1861-1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 93-95.

[6] Stacey Graham, Battle of Murfreesboro (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society, 2017), accessed at Tennessee Encyclopedia, https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/battle-of-murfreesboro/ (hereafter TNE); The Buffalo Commercial, 22 December 1862; Delurah Hendershot, 1860 United States Federal Census, available from Ancestry.com. The text regarding Robert’s heroism brags that he had fought in “five battles, Lebanon, Murfreesboro, Chattanooga, Shiloh, and Fredericksburg.” However, this is mostly fabricated, because the 9th Michigan did not see combat in Lebanon, Chattanooga, or Shiloh, meaning that Robert most likely only participated in the battles of Murfreesboro and Fredericksburg.

[7] The Buffalo Commercial, 22 December 1862; Olson, Music and Musket, 60.

[8] The Buffalo Commercial, 22 December 1862.

[9] The Buffalo Commercial, 22 December 1862.

[10] Joseph F. Kett, “Adolescence and Youth in Nineteenth-Century America,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 2, no. 2 (1971): 290-293.

[11] Detroit Free Press, 20 December 1862.

[12] The Leavenworth Times, 20 May 1863; New-York Tribune, 18 April 1863.