Reflections from Appomattox: Molly Graham Discusses Her Internship at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park

by Molly Graham | | Saturday, October 23, 2021 - 11:48

My name is Molly Graham, and I am a fourth-year student studying History and Government at the University of Virginia. This summer, I interned at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, the place where General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, signaling an end to the Civil War. As a Cultural Resources intern, I worked under both the curator and the historian at the park. Throughout my time at APCO (Appomattox’s official National Park System acronym), I learned a great deal about public history and conservation, all while partaking in the process myself.

For three days a week, I interned under Ann Roos, the curator at APCO. For most of the summer, I worked on the annual inventory lists that the curator must complete, detailing whether the objects in the museum collection were present and whether they were damaged. We searched throughout the village looking for controlled property (rifles and cannons) and random accession objects from the 1950s (like a crock or a metal square). This sounds easy enough, but some of these objects had not been found for decades! Nevertheless, we looked everywhere for the objects and rejoiced (a lot) when we found them. Furthermore, some days we completed housekeeping in the historic buildings in the village. This included vacuuming a 19th-century sofa (in the proper method), dusting in curatorial storage, and even cleaning bird poop off the floor (so glamorous)!

Furthermore, every month we performed Integrated Pest Management, or IPM for short. We walked around all the buildings in the village and collected last month’s sticky traps, recording the pests that surfaced and determining if they were hazardous to the museum collection or not. We often found silverfish, clothes moths, and carpet beetles, among others—all pests that can wreak havoc on an object. I also learned how to take light readings to monitor the visible light and UV light exposure on objects. Before my internship, I never realized that museums monitor for pests or light, and never considered how valuable that data is for the curator.

Towards the end of my internship, I made over fifty deaccession packets and cataloged and labeled various objects to add to the collection. Staff members make a deaccession packet for an object that the park wants to remove from the collection. In this circumstance, the objects were outside the scope of the collections (like a sofa in poor condition with no provenance to the park), so the curator decided they should no longer be museum property. When this happened, I would search the accession files, ICMS (Interior Collections Management System), the paper catalog, and the Historic Furnishing Reports to find as much information as I could about that specific object. Then, I wrote a detailed summary of my findings. I also cataloged new objects in the collection, adding them to the National Park Service’s online catalog system and physically labeling the objects.

On the other two days of the week, I worked under the historian at APCO, Patrick Schroeder. I helped put together a mass casualty list of the soldiers who were wounded, killed, captured, or reported missing between April 2 and April 9, 1865. Evidently, a mass casualty list for the Appomattox Campaign had never been completed, so it was nice to contribute my own research to this endeavor. This project included searching through regimental histories and other casualty lists to determine a soldier’s rank, name, type of casualty (wounded, mortally wounded, killed, captured, or missing), and the date on which the casualty occurred. Oftentimes, a soldier’s name would be spelled incorrectly, so I would have to dig through multiple sources to figure out what his actual name was. Although this was a time-consuming process, it was rewarding when I discovered soldiers’ stories and could bear witness to their memory.

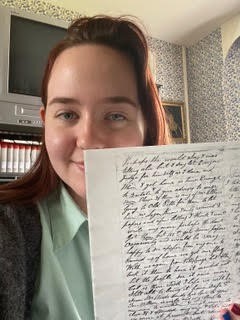

I also spent time transcribing historical documents. We mainly focused on the diary of a Maine infantryman, Edwin Emory. Emory often wrote about camp life and the weather, but he had incredible insight into some major events that occurred during this period of the war. In one section, he remarked about the United States Colored Troops, expressing, “I welcome them to this army, and am glad to see them dressed in Uncle Sam’s ‘blue’, and prepared to fight for their freedom, and for a country that has misused and wronged the colored race deeply.” In another part of his diary, Emory articulates his grief over the assassination of President Lincoln, and declares, “Into other hands the government will pass, but the acts of Abraham Lincoln are imperishable, and the will and fixed determination of the people are not destroyed. They will preserve the government. Deo volente, and establish it on a sure basis of which freedom is the cornerstone.” On a lighter note, Emory frequently complained for weeks that he had not received a letter from his “dear Louise,” presumably his wife. Finally, he did, and the suspense was over! Even though transcription was often a tedious task, I loved the excitement of deciphering a word and understanding the author’s thoughts.

It was an absolute joy and honor to spend my summer at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park. As a Lynchburg native, I never realized that such an incredible place, filled with amazing people, was just down the road from me. I have garnered a greater appreciation for the National Park Service and conservation in general. I see myself volunteering in some capacity at an NPS or historic museum site in the future. Thank you so much to the Nau Center for supporting this internship! It is such an incredible opportunity that I wish many others can have in the future.

Images: (1) Appomattox Court House, (2) Molly Graham with one of the letters she transcribed