Although he would later do so in the classroom as a matter of routine, the first time that University of Virginia Professor Albert Henry Tuttle ever presided over a large group of white southern young men was as a Union soldier on prison guard duty during the Civil War. Born in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio in 1844, Tuttle enlisted in the Eighth Ohio Independent Battery at the age of nineteen and spent his Union service keeping watch over captured Confederates on Johnson’s Island in his home state. After the war he became an internationally recognized scholar in the fields of zoology and biology. In 1888 Tuttle arrived to chair a department at UVA—where he would teach for twenty-five years. At the time that he lived and worked in Charlottesville, his Union service might have set him apart from his colleagues and alienated him from his environment at the university. Around the turn of the century, the University of Virginia was a bastion of Lost Cause veneration for the Confederacy. Yet the Ohioan Tuttle embraced the historical inheritance of his setting, expressed admiration for Confederate leaders, and appears to have had no issue living among former adversaries. In fact, he chose to be buried among them. When he died in 1927, his obituary in the Alumni Bulletin made no mention of his Union past.[1]

Tuttle embodied the “reconciliationist” trend in American social and cultural life in the late 1800s when it came to the memory of the Civil War. Historians like David Blight and Nina Silber describe reconciliationists as those white Americans who, in an effort to bury the hatchet in the decades after the war, subscribed to and promoted a narrative of Civil War memory that found room to celebrate qualities in both sides. They emphasized the shared American attributes of duty and valor displayed by both the Union and the Confederacy during the late conflict and exalted the restored nation that had emerged from it. Many white northern veterans in the late nineteenth century displayed a ready willingness to pay respect to former Confederates’ pluck and fortitude, if not necessarily the cause they fought for, in the name of future cooperation as a reunified country. Tuttle appears to have been one of them. In a sense, Tuttle “clasped hands across the bloody chasm” – to use Horace Greeley’s 1872 phrase – with his academic colleagues at UVA on a daily basis. The fact that he not only lived but thrived in the heart of the Old Dominion speaks to the degree to which many white Americans proved able to find common ground with their former foes in the decades following the Civil War. Not all northerners shared his inclination, of course. Nau Center director Caroline Janney has written about the limits of reconciliation during this period, particularly among veterans. In Tuttle’s case, his warm postwar conception of and demeanor toward white southerners may have reflected the relatively mild nature of his wartime experience.[2]

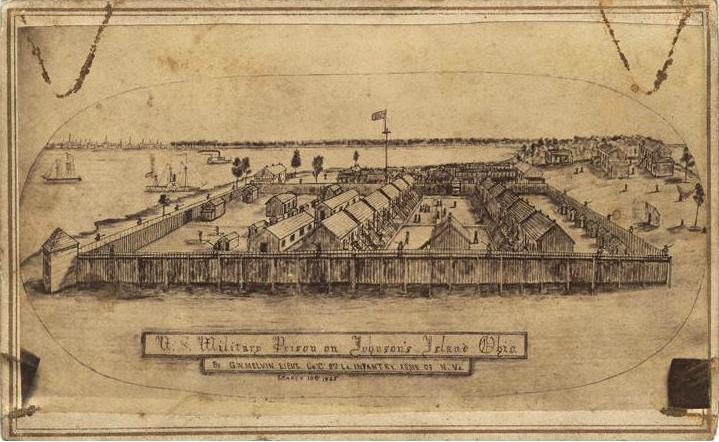

Tuttle’s own involvement in the war extended only as far as guarding Confederate prisoners, all of whom were officers, and lasted a mere two months. His unit, attached to the Ohio National Guard, never left its home state and suffered no attrition. The facility at Johnson’s Island, near Sandusky, where Tuttle spent August through October of 1864, possessed the lowest mortality rate of any prisoner of war camp in the North and a reputation among captured Confederates as one of the Union’s most hospitable prisons. Private Tuttle was one of about 400 Union soldiers keeping the roughly 2,600 captive rebels there under guard. Life on remote Johnson’s Island during the late summer of 1864 must have felt far removed from the horrors of war happening simultaneously elsewhere. Tuttle was present for the final execution carried out at the camp: the September 2nd hanging of a Kentucky rebel convicted by a court martial of murdering several Union soldiers. In general though, Tuttle’s experience was not one likely to have instilled a deep bitterness toward Confederates. He did no hard marching, no fighting; saw no friends suffer and die. Though he technically did his Union duty, Tuttle likely did not hear a single shot fired in anger during the war, a fact that may go a long way toward explaining his postwar bearing.[3]

After the Civil War, Tuttle threw himself into his studies. Excelling across a number of scientific fields, he acquired impressive educational credentials and quickly built a reputation as a top-notch teacher and laboratory leader. In the early 1870s he became one of Louis Agassiz’s last students at Harvard University. Though now discredited and condemned by history, Agassiz was at the time still a prestigious figure and counted among the thought leaders of the scientific world. In 1873, the same year he married his wife Kate Seeley in Paris, Tuttle became one of the original faculty members of the Ohio State University, where he instructed students in microscopy, histology, bacteriology, zoology, and comparative anatomy for fifteen years. In 1888, Tuttle applied for and was selected as the new Miller Chair of Biology and Agriculture at the University of Virginia, and moved his wife and three children south to Charlottesville.[4]

Described by his associates as an “independent Republican” in politics, Tuttle arrived to a university town that had become a repository of the Lost Cause tradition. The white community of the University of Virginia looked backward with considerable pride at its Confederate heritage. Some of Tuttle’s new colleagues included Confederate veterans William E. Peters (Latin), John W. Mallet (Chemistry) and Charles S. Venable (Mathematics), who all possessed distinguished war records. Tuttle’s former boss, R. D. Bohannon, however, predicted the Ohioan would have no difficulty fitting in. Writing to Venable in support of Tuttle’s appointment, Bohannon explained that “one does not feel that he [Tuttle] is a ‘Yankee’ or ‘Westerner’ but a genuine old Virginian.” His assessment proved apt. Tuttle flourished at the University of Virginia and enthusiastically proceeded to put down roots. He lived in Pavilion I on the West Lawn. His daughter Anna became an assistant librarian and married Professor W. H. Heck—a southerner. Tuttle immersed himself in his work and made a reputation for himself as a lively participant in the intellectual community. In 1890, he gushed that UVA was “a place that is a university morning, noon, and night, for six days in the week, and where we go to a university chapel on Sundays.” No evidence exists of any friction arising out of his past Union service. At one point he even declined the presidency of the Ohio State University in order to stay in Charlottesville. Tuttle remained on the faculty for a quarter century, living and working to the end of his career as an unassuming example of reconciliation between the sections. He built a considerable legacy as a teacher and today a dormitory on grounds bears his name.[5]

In 1912, the year before Tuttle retired, the University hosted a reunion of its Confederate alumni. Tuttle was undoubtedly one of, if not the only, Union veterans on grounds for the gathering. His thoughts on the occasion are not recorded, though his long-time colleague John W. Mallet gave an address. The episode encapsulated Tuttle’s peculiar place at UVA, as a solitary Union veteran hidden amid a veritable cavalcade of Confederate honorees. Looking back, one is tempted to think of him as isolated and lonesome at the university by virtue of his situation. Yet Tuttle clearly felt he had found a place for himself and his family in Charlottesville. His personal papers, now housed by the university’s special collections, contain dozens of newspaper clippings extolling the virtues of Jefferson, Stonewall Jackson, and Robert E. Lee—among others. His Union service did not stop Tuttle from exhibiting a great deal of respect for his former enemies or for the South as a region. Indeed, he had all but become the very “old Virginian” that Bohannon predicted. As Gary W. Gallagher has written, reconciliation “often was characterized by a measure of northern capitulation to the white South and the Lost Cause tradition,” a trend which Tuttle appeared to personify. Though he died in California, he is buried at the university, a member of its community now in perpetuity. Ultimately, Tuttle’s life and career at UVA represents a case study of reconciliation between white Americans after the Civil War, and the degree of his assimilation to the community adds another facet to our understanding of the University of Virginia’s history in connection with those who wore Union blue.[6]

Clayton J. Butler is a PhD candidate in the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. His research investigates white Unionists in the Deep South during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Images (1) Albert Henry Tuttle (courtesy Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia); (2) Johnson’s Island Military Prison (courtesy Wikicommons); (3) Tuttle with His Family on the Lawn (courtesy Small Special Collections Library).

Notes

1. Albert Tuttle Papers, 1864-1926, Accession #7327-a, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va. Hereafter cited as “Tuttle Papers”; Lyon Gardiner Tyler, ed. Men of Mark in Virginia: Ideals of American Life; A Collection of Biographies of the Leading Men in the State, Vol. 5 (Men of Mark Publishing Company, 1909), 430-431; University of Virginia Alumni News, Vol. 2 (Alumni Association of the University of Virginia, 1913), 5.

2. Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 6; Gary W. Gallagher, Causes Lost, Won and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 33; see also David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001) and Nina Silber, The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865-1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

3. Roger Pickenpaugh, Johnson’s Island: A Prison for Confederate Officers (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 2006), 30, 35-36, 45, 54, 92.

4. Oakland Tribune (Oakland, CA) January 25, 1927. Newspapers.com; Tyler, Men of Mark in Virginia, 431.

5. Dan R. Frost, Thinking Confederates: Academia and the Idea of Progress in the New South (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 40; R.D. Bohannon to Charles Scott Venable, May 18, 1888. Letters Concerning the Appointment of Albert H. Tuttle to the Chair of Biology and Agriculture at the University of Virginia, 1888, Accession # 12368, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

6. Gallagher. Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten, 33.