After the Civil War, the University of Virginia and its alumni played a leading role in propagating the mythology of the Lost Cause. Determined to “vindicate the character of the South,” they defended secession, valorized Confederate soldiers, and declared the postwar experiment in biracial democracy a failure. Few alumni challenged this culture of Confederate orthodoxy, and even fewer openly defended Reconstruction. Among those who did, however, was Alexander Rives, an eccentric but fiercely principled Charlottesville jurist. He was a Jacksonian Democrat who became a devoted Whig and then a pillar of the state’s Republican Party—a planter and proslavery Unionist who became a champion of Black suffrage and civil rights. Rives and other White Republicans joined African Americans in repudiating the Lost Cause and resisting the Democratic “redemption” of the South. Although their efforts failed, they spoke to the possibilities of the postwar world and revealed enduring divisions in the nineteenth-century “Solid South.”[1]

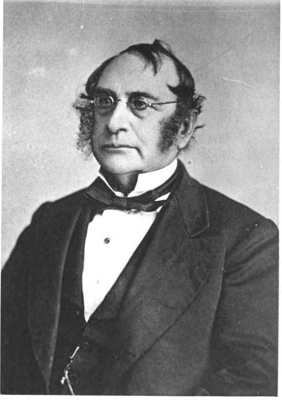

Alexander Rives was born in Nelson County, Virginia, on June 17, 1806, to Robert Rives and Margaret J. Cabell. His father was a wealthy merchant and Revolutionary War veteran, and his mother belonged to one of the elite self-anointed “First Families of Virginia.” Rives graduated from Hampden-Sydney College in 1825 and enrolled at the University of Virginia three years later to study law and moral philosophy. There, he caroused and often flouted the uniform code, but he earned the scholarly respect of his peers and professors. On April 4, 1829, he married Isabella Wydown, the daughter of an Episcopalian minister, and he withdrew from the university nine days later.[2]

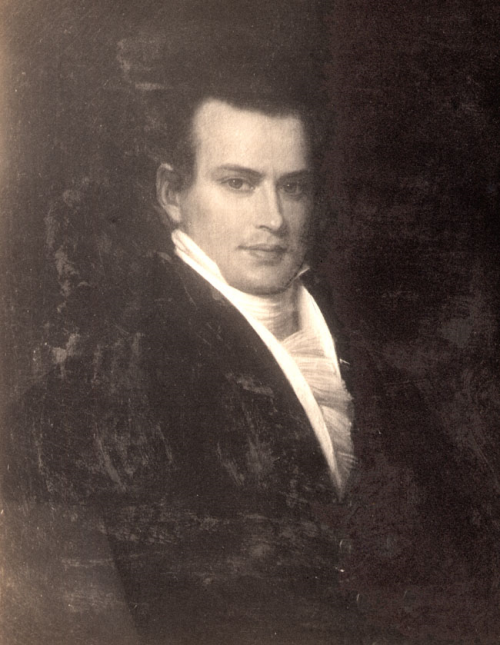

Rives settled in Charlottesville, where he practiced law and pursued a career in politics. Three of his brothers had served in the General Assembly, and one—William Cabell Rives—eventually became a United States senator. Following in their footsteps, he won a seat in the Virginia legislature in 1834 and held it on-and-off for the next eight years. Although he began his career as a Democrat, he broke ties with the party over President Martin Van Buren’s independent treasury plan. He ultimately embraced the Whig Party’s vision of moral and economic reform. He served as a trustee for the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute, helped manage the Rivanna Navigation Company, and raised money to extend the Louisa Railroad through Charlottesville.[3]

Rives also supported the Virginia Colonization Society, which he viewed as a bulwark against sectional extremism. In 1838, he insisted that colonization met the “demands of Southern patriotism and benevolence” and offered “all parties and every section, a common ground of resistance against the mischievous and reckless enterprises of Abolition.” The program, he claimed, provided political stability for the Union while securing “peace, happiness and prosperity” for free African Americans. In the antebellum era, some southerners still hoped that colonization would lead to gradual emancipation. Rives, however, appeared firmly committed to slavery, and as late as 1860, he held 66 people in bondage.[4]

Nonetheless, Rives was a passionate, lifelong Unionist. During the nullification crisis of 1832-33, he denounced South Carolina’s “disorganizing doctrine” and corresponded with James Madison to clarify the balance of state and federal power. In 1850, as several southern states contemplated secession, Rives declared the Union “priceless” and worked to restore the “kindly feelings of brotherhood” between North and South. He clung to the political middle ground, denouncing the “wild and wicked fanaticism” of abolition as well as the “violence and ultraism” of secession. Well into the 1850s, he celebrated the crumbling Whig Party as the “only true national party,” and in 1860, he was an alternate delegate to the Constitutional Union National Convention.[5]

During the winter of 1860-61, Rives fought desperately to avert secession and civil war. He hoped to build a broad, conservative coalition, uniting congressmen from the Upper and Border South with “our Douglas allies” in the North. Together, he predicted, they could neutralize Republican power and stem the tide of secession. With conservatives united against him, Rives observed, President Abraham Lincoln would “find it necessary…to make satisfactory concessions to the yet loyal slave states.” Then, in the next presidential election, they could peacefully “overthrow the [Republican] party in 1864.”[6]

When Governor John Letcher called a secession convention, Rives urgently rallied Unionist voters. He recognized that a violent “distemper” had “seized upon the minds of our people,” and that secessionists were using violence and intimidation to suppress dissent. Even so, Rives vowed to withstand the “passions of the people” and “satisfy his own conscience.” Conditional Unionists held the balance of power in the convention, and on April 4, they voted overwhelmingly against secession. A little more than a week later, however, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, prompting Lincoln to call for 75,000 volunteers. Forced to take sides, Virginia’s delegates passed an Ordinance of Secession on April 17. Rives remained loyal to the Union, lamenting the state’s “unexpected transfer to [Confederate President] Jeff. Davis.” With “Terrorism…reign[ing] through the land,” however, he reckoned that further resistance would prove futile. Unwilling to recognize the Confederacy, he largely retreated from public life for the next four years.[7]

Decades later, a local writer recalled Rives’s bitter contempt for the Confederacy. Rives, he reported, was a “violent Union man” who “never contributed a penny towards [the Confederacy].” Rives refused to sell his crops to the Confederate government, and when his son enlisted in the army, he denied him “any material aid.” In 1865, an editor observed that Rives “denounced the heresy [of secession] from the start, and denounced it to the bitter end,” and another writer pronounced him a “consistent Union man throughout the war.” For Rives, the sectional crisis brought only tragedy. His wife died on March 24, 1861, and his Confederate soldier son Charles—another UVA alumnus—died at the Battle of the Cold Harbor in June 1864. Forty-two years later, the university added two bronze tablets on the Rotunda, commemorating Charles and 500 other students who “lost their lives in the military service of the Confederacy.”[8]

Few sources document the impact of the war on the 66 Black men, women, and children that Rives held in bondage. Because the Union army made few incursions into Albemarle County, slavery did not disintegrate as rapidly as it did in other parts of the Confederacy. Nonetheless, the county’s African Americans seized opportunities for freedom throughout the war, and at least 250 Black men born in Albemarle County served in the Union army. Although most of these men had fled or been taken from the county during the antebellum era, some escaped from Confederate-occupied Virginia during the war and made their way to Union lines. The Nau Center’s Black Virginians in Blue website uncovers these men’s stories.[9]

After the war, Rives returned to public life to play an important role in Reconstruction. As a conservative Unionist, he hoped to quickly reunite the country and leave the South’s social structure essentially intact. In June 1865, he met with President Andrew Johnson to discuss the “mode of restoring [Virginia] to the Union.” Rives urged him to punish Confederate leaders, observing that “some have been pardoned from this State, who little deserved it.” He viewed poorer southerners, however, as innocent victims of the war’s devastation. He accused Confederate leaders of “suppressing the will of the people” and stifling their “true voice by threats of violence,” and he asked Johnson to “lean to mercy.”[10]

Rives also helped organize a public meeting in Charlottesville that June. Union victory, he observed, had settled the “great questions” of the war, and he urged the crowd to accept the “inevitable demands of the occasion.” Having lost the war, Virginians had a duty to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment and offer “loyal submission to the federal government.” At the same time, however, he argued that military rule “contravene[d] the fundamental principles of [republican] government,” and he warned northerners that it was “not reasonable to suppose that the people could or would ultimately accept [it] in silence.” Looking toward the future, Rives hoped to quickly restore civilian self-government, “remove all just grounds of discontent,” and “prevent future disaffection.”[11]

In June 1865, Governor Francis Pierpont appointed a slate of Unionists to UVA’s Board of Visitors, including Alexander Rives, Thomas J. Pretlow, and Samuel H. Lewis. In their first meeting, Rives praised the faculty for keeping the university open during the war, observing that their “fidelity and constancy” had prepared UVA for “immediate usefulness on the return of Peace.” That fall, political allies urged Rives to run for Congress. As one writer explained, he was “national, conservative, and Union in all his feelings and principles”—a man acceptable to “North, South, East, [and] West.” Rives, however, refused to run, and the following year, he accepted a seat on the Virginia Court of Appeals.[12]

By 1867, Rives’s Unionism led him to embrace the Republican Party. As former Confederates reasserted political power, he “deemed it a duty to lift his voice with other Union men in repudiation of our [former] leaders.” He endorsed African-American suffrage, declaring the “ballot box the only safeguard for the interests and liberty of the freedmen.” He argued that African Americans deserved “all the rights of citizenship,” and he urged the state to abolish “all distinctions of civil or political rights founded on race.” He qualified this support, however, by calling for “property and educational qualification[s]” for voting—policies that would effectively disenfranchise many former slaves. That fall, Albemarle County’s moderate Republicans nominated him for a seat in the Virginia constitutional convention. The county’s African American majority, however, overwhelmingly supported Radical Republican candidates, and they elected Black Virginian in Blue James T. S. Taylor to the convention.[13]

Pierpont’s term as governor expired in January 1868. With Virginia undergoing military Reconstruction, General John Schofield held the power to appoint Pierpont’s successor, and he immediately offered the position to Rives. Schofield declared Rives “invaluable to the Union Cause,” and General Ulysses S. Grant considered him the best man for the job. Ultimately, however, Rives declined the offer and remained on the Bench. Later that year, the Republican State Committee named him as a delegate to the party’s national convention. Although he was unable to attend, he championed Grant’s candidacy, insisting that his victory would ensure the “prosperity and peace of the country.”[14]

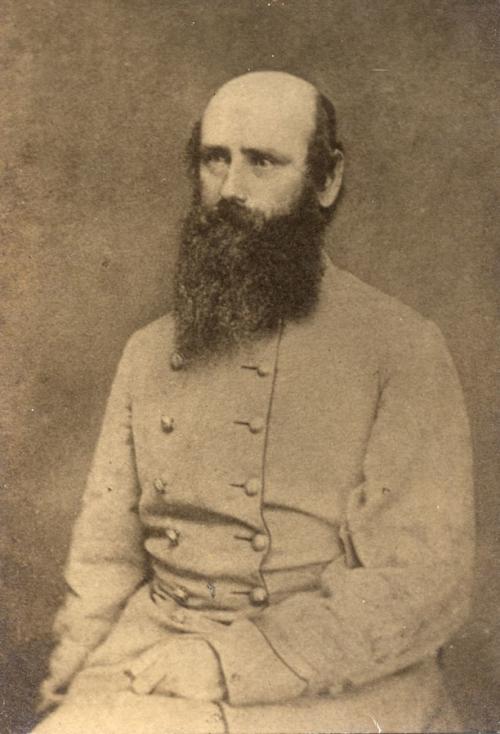

In April 1870, Rives served as president of the Republican State Convention. There, appealing to wartime Unionists, he “urged those who had fought with him…under the old Union banner to come out on the Republican side.” He called for a “thorough organization of the party” across the state and worked to unify moderate and Radical Republicans. The party’s platform upheld the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, proposed funding for public education and internal improvements, and offered “hearty and generous support” to President Grant. Rives ran for Congress that October but lost to “Conservative” candidate R. T. W. Duke. As Virginia’s Reconstruction drew to a close, Rives’s allies lobbied Grant to appoint him to the federal judiciary. General George Stoneman, for example, praised Rives’s “well tested and long tried patriotism” and declared him “one of the ablest jurists and most consistent Union men in the State.” In response, in February 1871, the president appointed him to the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia.[15]

As a district court judge, Rives worked to balance sectional harmony with racial justice. In 1872, voters elected several former Confederates to the Virginia General Assembly. Although the Fourteenth Amendment barred the men from holding office, Rives ruled that President Andrew Johnson’s amnesty proclamation took precedence, and he allowed them to take their seats. At the same time, however, he tried members of the Ku Klux Klan and actively included African-American men on his juries. As Democrats terrorized and disenfranchised African Americans across the South, Rives fiercely defended their political rights. In 1873, he insisted that it was illegal for election officials to form separate lines for White and Black voters, “especially when done to prevent a part of the voters from casting their ballots.” When a lawyer claimed that these separate lines prevented “bloodshed or riot,” Rives countered, “better even bloodshed or riot than that citizens should be prevented from casting their votes.”[16]

Rives’s most famous and controversial case came in 1878. African-American teenagers Lee and Burwell Reynolds had killed a White man in self-defense, and an all-White jury had promptly convicted Lee of murder. Their lawyers had demanded integrated juries and petitioned to move the trial into federal court, but the judge had denied both requests. The brothers appealed the case to Rives, who ruled that all-White juries violated Black defendants’ civil rights. He scheduled another trial and ordered federal marshals to impanel an integrated jury. Democrats denounced Rives’s ruling as an assault on state sovereignty, and the Supreme Court ultimately reversed it. As Justice William Strong explained, the Fourteenth Amendment protected African Americans from “State action, and against that alone,” and it was therefore powerless to prevent individual acts of discrimination.[17]

Despite his defeat, Rives took a rosy view of the Supreme Court’s ruling, observing that it protected African Americans from discriminatory laws. For years, he observed, southerners had regarded the Fourteenth Amendment as a “mere paper guarantee,” which they could “deride and evade” with impunity. Now, he predicted, it would become a “living and prevading [sic] force throughout the States.” He hoped the ruling would remind southerners of their “constitutional obligations” and bring an end to the “disorders and oppressions that have been such a disgrace to the South.”[18]

For the rest of his life, Rives worked to build a viable Republican Party. In the early 1880s, however, his health began steadily declining. He resigned from the District Court in August 1882 and retired to “Eastbourne Terrace,” his Charlottesville estate. He died there on September 17, 1885, at the age of 79. A week later, a local editor published a stirring eulogy, praising Rives as a “thorough gentleman,” a “pure and able jurist,” and a man of “scrupulous honor.” Throughout his life, Rives “pressed forward in the path of his duty, unmindful of popular clamor.” He possessed “deep, conscientious convictions and the courage and manhood…to adhere to what he believed to be right.” For this, and for his lifetime of service, the “Commonwealth had no truer, braver son than Alex. Rives.”[19]

By the 1880s, Democrats had reasserted control across the South and begun dismantling the achievements of Reconstruction. The Lost Cause mythology they created envisioned a White South united against the “radicalism” of biracial democracy. It demonized Republican White southerners as “Scalawags”—traitors to their region and their race. By upholding Reconstruction, a local writer recalled, Rives “lost the respect and regard of many of his people…both as a lawyer and a man.” Undaunted by popular scorn, however, Rives became a leader in the state’s Republican Party and a champion of civil rights. After the war, despite his background as a planter and proslavery Unionist, he worked to root out “all distinctions of civil or political rights founded on race.” In doing so, he issued a powerful challenge to the South’s hardening racial order. His efforts, though unsuccessful, testify to the postwar South’s enduring divisions and remind us that the advent of Jim Crow was not immediate, inevitable, or uncontested.[20]

Images: (1) Alexander Rives, (2) William Cabell Rives, and (3) Richard T. W. Duke (courtesty Wikicommons).

Notes:

[1] Albert T. Bledsoe, Is Davis a Traitor, or Was Secession a Constitutional Right (Baltimore: Innes & Company, 1866), v. See James Alex Baggett, The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003); Victoria E. Bynum, The Long Shadow of the Civil War: Southern Dissent and Its Legacies (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010); Carl N. Degler, The Other South: Southern Dissenters in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Harper and Row, 1974).

[2] Bulletin of Hampden-Sydney College: General Catalogue of Officers and Students, 1776-1906 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1908), 61; A Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Fifth Session, 1828-1829 (Charlottesville: Chronicle Steam Book Printing House, 1880); Judges of the United States (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1978), 36. In May 1829, Rives mediated a tense dispute over UVA’s commencement day ceremony. The faculty had recently approved a plan giving them the power to select the day’s four student speakers. In response, dozens of students gathered at the Rotunda, decrying the “offensive” plan as an attack on their “independent and republican think[ing].” The faculty, in turn, declared these resolutions “disrespectful” and demanded that they retract them. After a four-day standoff, students asked Rives to intervene, and he offered chairman Robley Dunglison a compromise: the faculty would select two speakers, and the student body would select the other two. Dunglison accepted Rives’ “conciliatory designs,” and students subsequently withdrew their resolutions. See Session 5 of the Chairman’s Journal, September 7, 1828 – July 20, 1829, available from http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu.

[3] Lyon Gardiner Tyler, Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, Vol. III (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1915), 17; The Richmond Enquirer, 24 January 1837, 10 July 1838, 10 September 1841, 6 February 1844, and 11 November 1845.

[4] The Richmond Enquirer, 18 January 1838; 1850 U.S. Federal Census- Slave Schedules and 1860 U.S. Federal Census- Slave Schedules, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[5] Alexander Rives to James Madison, 28 December 1832, James Madison Papers, Library of Congress; Richmond Enquirer, 16 April 1850; Daily American Organ, 17 July 1856; Alexandria Gazette, 28 February 1860 and 6 December 1860.

[6] The Alexandria Gazette, 6 December 1860; Alexander Rives to Alexander H. H. Stuart, 20 November 1860, The Valley of the Shadow Project, available from https://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/A8015; Alexander Rives to John B. Minor, 25 January 1861, Jefferson’s University: The Early Life, available from http://juel.iath.virginia.edu.

[7]Alexander Rives to John B. Minor, 25 January 1861, Jefferson’s University: The Early Life, available from http://juel.iath.virginia.edu; Alexander Rives to Alexander H. H. Stuart, 13 May 1861, The Valley of the Shadow Project, available from https://valley.lib.virginia.edu/papers/A8017.

[8] R. T. W. Duke, Jr., “The Albemarle Bar IX,” Virginia Law Register, Vol. 7 (October 1921), 445; Alexandria Gazette, 29 March 1861; The Norfolk Post, 5 August 1865; Richmond Dispatch, 7 May 1866.

[9] Ervin L. Jordan, “Charlottesville During the Civil War,” Encyclopedia Virginia, 14 December 2020, available from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/charlottesville-during-the-civil-war.

[10] The Evening Star, 14 June 1865; Alexander Rives to Andrew Johnson, 12 July 1865, in The Papers of Andrew Johnson, Vol. 8: May-August 1865, ed. Paul H. Bergeron et al. (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1989).

[11] The Evening Star, 14 June 1865; The New York Times, 15 June 1865; Alexander Rives to Andrew Johnson, 12 July 1865, in The Papers of Andrew Johnson, Vol. 8: May-August 1865, ed. Paul H. Bergeron et al. (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1989).

[12] University of Virginia Board of Visitors Minutes, 5 July 1865, available from http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; The Norfolk Post, 5 August 1865. See Lawrence M. Denton, Unionists in Virginia: Politics, Secession and Their Plan to Prevent Civil War (Charleston: The History Press, 2014); Alan B. Bromberg, “The Virginia Congressional Elections of 1865: A Test of Southern Loyalty,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vo. 84, No. 1 (January 1976), 75-98; Lewis F. Fisher, No Cause of Offence: A Virginia Family of Union Loyalists Confronts the Civil War (San Antonio: Maverick Publishing Company, 2012).

[13] The Norfolk Post, 5 August 1865; Richmond Dispatch, 7 May 1866 and 28 February 1868; Alexandria Gazette, 28 May 1867.

[14] Richmond Dispatch, 3 October 1867, 24 October 1867, 18 May 1868, and 19 August 1868; Staunton Spectator, 29 October 1867; John Schofield to Ulysses S. Grant, 4 April 1868, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 18: October 1, 1867-June 30, 1868, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991), 227.

[15] Richmond Dispatch, 22 April 1870, 23 April 1870, and 5 December 1870; George Stoneman to Ulysses S. Grant, 17 July 1868 and 28 September 1869, The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 19: July 1, 1868-October 31, 1869, ed. John Y. Simon (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995), 275.

[16] The Richmond Dispatch, 2 March 1872; The Daily State Journal, 20 September 1872 and 1 April 1873; The Alexandria Gazette, 16 May 1872;

[17] Rogers M. Smith, Civil Ideals: Conflicting Visions of Citizenship in U.S. History (New haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 380; Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313 (1880), available from http://www.supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/100/313.

[18] The Valley Virginian, 25 March 1880.

[19] The Norfolk Virginian, 16 August 1873; The Baltimore Sun, 11 July 1881; Richmond Dispatch, 26 March 187318 September 1885; The Valley Virginian, 24 September 1885.

[20] Duke, “The Albemarle Bar,” 446.