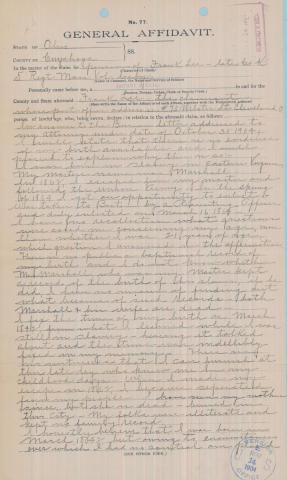

In 1905, forty years after the end of the Civil War, an Albemarle-born, African-American veteran named Frank Lee applied to receive an increase in his pension. He had served as a young man in the 5th Massachusetts Colored Volunteer Cavalry, a black regiment that fought for the Union cause. Because of his service, he was eligible for government assistance in the form of pensions, but he needed to verify one thing: his date of birth. Frank Lee set out to clarify. “I will state that there is no evidence of my birth available and I will proceed to explain why this is so,” Lee said in an official pension application document. “I was born in slavery in Eastern Virginia. My master’s name was Marshall. In 1862, I escaped from my master and followed the Union Army. In the spring of 1864 I got an opportunity to enlist—was taken to Boston by a Recruiting Officer and duly enlisted on March 16, 1864.”

Considering his lack of personal records, Lee’s success in the pension process counts, along with his escape from slavery and contribution as a Union soldier, as a feat. Historian Donald R. Shaffer has shown that white veterans and their survivors were statistically more likely to receive pensions than African Americans. Obstacles such as illiteracy and poverty made the bureaucratic process and the travel to various agencies it required difficult. For Frank Lee, the legacy of slavery complicated his own application. The records of Lee’s pension application reinforce Shaffer’s notion of skewed government ministrations for black veterans; the records of Lee’s time as a soldier, however, reveal more: the heroism and compelling escapades of his regiment, the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry.

Frank Lee was one of hundreds of African American men who decided to enlist in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, which trained in Massachusetts before traveling to and camping in Virginia, eventually aiding in the Union’s capture of the Confederate bastion, Richmond. Frank was not, however, the only private in the regiment who had fled Charlottesville. A man named Henry Lee, possibly Frank’s brother and whose service records also indicate his place of birth as Albemarle County, enlisted at the age of 22 in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry on April 30, 1864, one month after Frank’s date of enlistment.

Frank and Henry Lee were two of eight Albemarle-born, black Union soldiers identified as having served in black Massachusetts volunteer regiments. The other six men were members of either the 54th or 55th Massachusetts Infantry, the former serving as the subject of the 1989 film Glory. Historian Douglas Egerton notes that the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments largely recruited free African American men from the North, while the 5th Massachusetts, being a cavalry regiment, sought potential soldiers hailing from the South, the American region thought to yield more skilled horsemen. Accordingly, Frank and Henry Lee, two Albemarle-born men, became part of the North’s first black cavalry regiment.

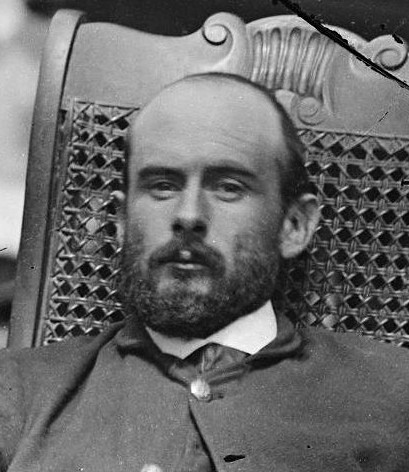

Leading the regiment were appointed white officers. The young colonel in charge was a named Henry S. Russell, the cousin of the famed Civil War colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, who died in battle leading the Massachusetts 54th Regiment in 1863. Russell, like his cousin, became an admired leader. During the Union’s June 1864 Assault on Petersburg, a siege of which the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry was a part, Russell is said to have cried out, “Come on, brave boys of the Fifth!” before being shot in the shoulder. After Russell’s injury-induced resignation, the regiment’s men ran a piece in the Boston Liberator, thanking the Colonel for giving the soldiers, who included Frank and Henry Lee, “a character and reputation which it will be our constant endeavor to sustain.”

The man who replaced Russell was the wealthy Colonel Charles F. Adams, Jr.—the direct descendant of the two former presidents. The young scion’s 1864-1865 letters to his father reveal his racial prejudice but, in certain passages, a frankness: “Here too I first saw colored troops and they were in high spirits; for the evening before in the [Assault on Petersburg] they had greatly distinguished themselves and … had fought and fought fiercely,” Adams wrote to his father, then serving as U.S. minister to Great Britain. Adams was not the only famous last name to serve in the regiment: Charles R. Douglass, son of the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and Joshua Dunbar, father of the celebrated poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

With these men, Frank and Henry Lee journeyed down the eastern seaboard from Massachusetts, advanced on Petersburg, spent months guarding prisoners at a camp located at Point Lookout, Maryland, and even, during the months after the war’s official end, acted as an occupying force in Texas, ensuring no lingering trouble from the Confederates and keeping an eye on the French in nearby Mexico. Frank and Henry Lee’s service records indicate their detachment in August to September 1865 to the southernmost tip of Texas to work on a railroad line. According to his service records, just the previous August up at Point Lookout, Henry Lee was hospitalized for an illness. Fortunately, the next month he was back on duty, having improved in condition and avoided the fate of death by disease that swept many black Union soldiers.

What was perhaps the most triumphant moment for the Lees and the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry occurred in April 1865, when the soldiers marched through a conquered Richmond. The Union major who oversaw Richmond’s surrender said of the 5th Massachusetts cavalrymen, “I was told that this fine regiment of colored men made a very great impression on those citizens who saw it.” Frank and Henry Lee were back in their home state of Virginia, within dozens of miles of their birthplace, but this time in blue uniforms and atop military horses, the source of much awe for the recently freed African Americans of Richmond.

Both Frank and Henry Lee were mustered out of service October 31, 1865 in Clarksville, Texas—half a year after President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and five months after the end of the Civil War. Their whereabouts directly thereafter are not documented, but by 1900, according to the corresponding addresses in that year’s federal census and in Frank’s pension application, Frank Lee was a widower working as janitor and living alone in Cleveland, Ohio. Frank’s postbellum life is better documented than Henry’s, due largely to the existence of the former’s pension papers. There is no evidence that Henry either applied for or received a pension, so his location and livelihood throughout the decades following the war are not definitive.

In 1887, the three black Massachusetts regiments—the 5th, 54th, and 55th—organized a massive reunion in Boston. According to one newspaper correspondent for the New York Freeman, “The grand affair occurred at Tremont Temple last Monday morning, and was a brilliant success.… A profusion of national emblems, flowers and mottoes met the gaze everywhere.” Frank and Henry Lee, by then in their mid-forties, might have been in attendance, donning their old blue uniforms and parading down the streets alongside their companions from more than twenty years before. Having both survived the Civil War, the Lees were eligible for recognition, in the forms of both parade and pension. Three years after the reunion, the passage of the Dependent Pension Act of 1890, qualified all “invalid” Union veterans for pensions, no matter the cause of illness or injury. Frank Lee set forth to receive one.

To furnish proof of his physical debility, Frank had to make several visits to Ohio doctors. By fall of 1904, with doctors’ notes citing his “disease of heart and kidneys” and general weakening with old age, Frank was receiving eight dollars per month. By the next year, he was applying for an increase, listing the addition of his afflictions, including asthma and poor eyesight. Former slaves like Frank were less likely to have records of their birth or witnesses who could vouch about their early lives. “There are no witnesses that I can furnish at this late day who knew me in my childhood days,” Frank said, explaining in his pension application. “My folks were illiterate and kept no family record. I honestly believe that I was born in March 1842, but owing to circumstances over which I had no control am placed at a disadvantage in not being able to furnish proof of my age.” Frank’s testimony worked, and at the age of 63 he received an increase in his pension. For the soldiers of the 5thMassachusetts Cavalry, receiving a pension was an acknowledgement and commendation for their service in the Union army, which both Frank and Henry Lee certainly merited.

Jane Diamond is a rising fourth year undergraduate student at the University of Virginia, participating in the Distinguished Majors Program for History. As a summer 2017 intern for the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History, Jane works on the Center’s digital projects.

Images: (1) Deposition from Frank Lee's pension file, and (2) a close-up of Henry Lee's combined military service record (National Archives and Records Administration). (3) Charles Francis Adams, Jr., the second commander of the 5th MA Cavalry Regiment (Library of Congress).

Sources: Compiled Service Records, RG 94 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., accessed for Frank Lee and Henry Lee through Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/browse/273/); Pension records for Frank Lee, RG 15, National Archives and Records Administration; Douglas R. Egerton, Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America (New York: Basic Books, 2016); Steven M. LaBarre, The Fifth Massachusetts Colored Cavalry in the Civil War (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016); Donald R. Shaffer, After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004); Worthington Chauncey Ford, A Cycle of Adams Letters, 1861-1865, Vol. II (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1920); Handbook of Texas Online, George C. Werner, "Brazos, Santiago and Rio Grande Railroad," accessed July 10, 2017, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/eqb20; “Testimonial to Col. Henry S. Russell.” Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts) 24 Feb. 1865: 31. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, accessed May 23, 2017; J. Gordon Street, and Regular Correspondence of the Freeman. “The Veterans’ Re-Union.” New York Freeman (New York, New York) 6 Aug. 1887: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, accessed May 23, 2017.