Republican Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era

by Cecily N. Zander | | Tuesday, March 26, 2024 - 10:33

When historians say the Civil War pitted “brother against brother,” they usually mean siblings fighting against one another on opposite sides of the conflict: one wearing Union blue, the other Confederate gray. In the case of William Tecumseh Sherman and his younger brother, John, however, two siblings on the same side of the war found themselves in frequent disagreement, usually over military affairs. For historians, the prolific correspondence between the Sherman brothers provides striking insights into wartime tensions over how the United States could achieve military victory over the Confederacy. William, an 1837 graduate of West Point, railed against the inadequacies of the volunteer officers placed under his command: “In the war on which we are now entering,” he advised on May 20, 1861, “paper soldiers won’t do.” Meanwhile John, a Republican senator from Ohio, feared giving too much authority to West Point-trained officers. “The old army,” he explained in reply “is a manifest discredit." [1]

The two men were not alone in debating whether the United States ought to employ professional troops or citizen soldiers to bring about Union victory. Nor was their debate anything new. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Americans of all walks of life paid intense attention to military issues, though historians have not always noted these conversations. Scholars are content to portray the professional army as an insignificant factor in antebellum politics, largely because the regulars numbered only 16,000 enlisted men and officers and were spread out across the isolated territories of the American West. In fact, the professional force’s small size stood in reverse proportion to the attention it received from citizens who made American soldiers the object of intense political scrutiny.

John Sherman’s views on the marginal value of the nation’s professional army fixed him in lockstep with his colleagues in the Republican Party. This organization, which had formed in the mid-1850s out of the ashes of the Whig Party, possessed one guiding political principle: the non-extension of slavery into the American West. Some Republicans, especially those who would come to be labelled “Radicals,” believed in the abolition of slavery in the United States, but they were a minority within the party (albeit a vocal one).

It is perhaps not immediately obvious why a political party so exclusively concerned with the slavery issue would focus their ire on the professional army. Republicans directly linked the U.S. Regulars with the “Slave Power,” a shorthand description for the outsized and persistent influence slaveowners had exerted over national politics. Advocates of the Slave Power Conspiracy typically pointed to the bare facts: with less than one-third of the free population of the entire country, the slaveholding states had produced eleven of sixteen presidents, seventeen of twenty-eight Supreme Court justices, sixty-one of seventy-seven presidents of the Senate, and twenty-one of thirty-three Speakers of the House. To this compendium of political dominance, Republicans could easily have added sixteen of eighteen chairs of the House Military Affairs Committee and nineteen of twenty-two chairmanships in the Senate.

Political control provided one compelling piece of evidence to justify Republican suspicions about the professional army. But no statistic may have been as consequential as the fact that 313 commissioned officers of the regular army resigned their positions and joined the Confederacy in 1861. Though these men only accounted for 24% of the total officers in the antebellum army, their departures made those officers who remained suspicious by association. As Republican senator James W. Grimes of Iowa put it in 1862, all professional army officers, even those then fighting to save the Union, were “fully imbued with the State-rights, disunion, nullification, rebellious sentiment.” [2]

Republican suspicion regarding the professional army played a factor in their decision to rely on volunteer troops, not regulars, to fill the ranks of Union armies. While placing more than 2 million volunteers in blue uniforms, Republicans voted to increase the size of the regular army by a mere 10,000 troops (ten regiments) during the war, from 15,000 in 1860 to 25,000 in January 1863. On January 1, 1863, when the combined strength of Union armies stood at 918,191 men, regulars made up 2.7% of the total. And so, while West Point graduates and regular army officers such as Sherman, Ulysses S. Grant, George G. Meade, and Philip H. Sheridan led Union armies to victory, their performances did little to repair professional soldiers’ reputation in Republican minds. In fact, Republican politicians were more than happy to play down the achievements of West Pointers to avoid too much praise for regular army officers. In 1862, for example, after the battle of Fort Donelson Michigan senator Zachariah Chandler proclaimed, “there was but one regular officer . . . [and] not a regular soldier there.” [3] The point was to elevate the contributions of volunteer soldiers over those of the regulars. Chandler knew as well as anyone that West Point graduates such as Ulysses S. Grant (class of 1843), James B. McPherson (1853), and Charles F. Smith (1825) were among the officers critical to the success of Union operations on the Cumberland River that spring.

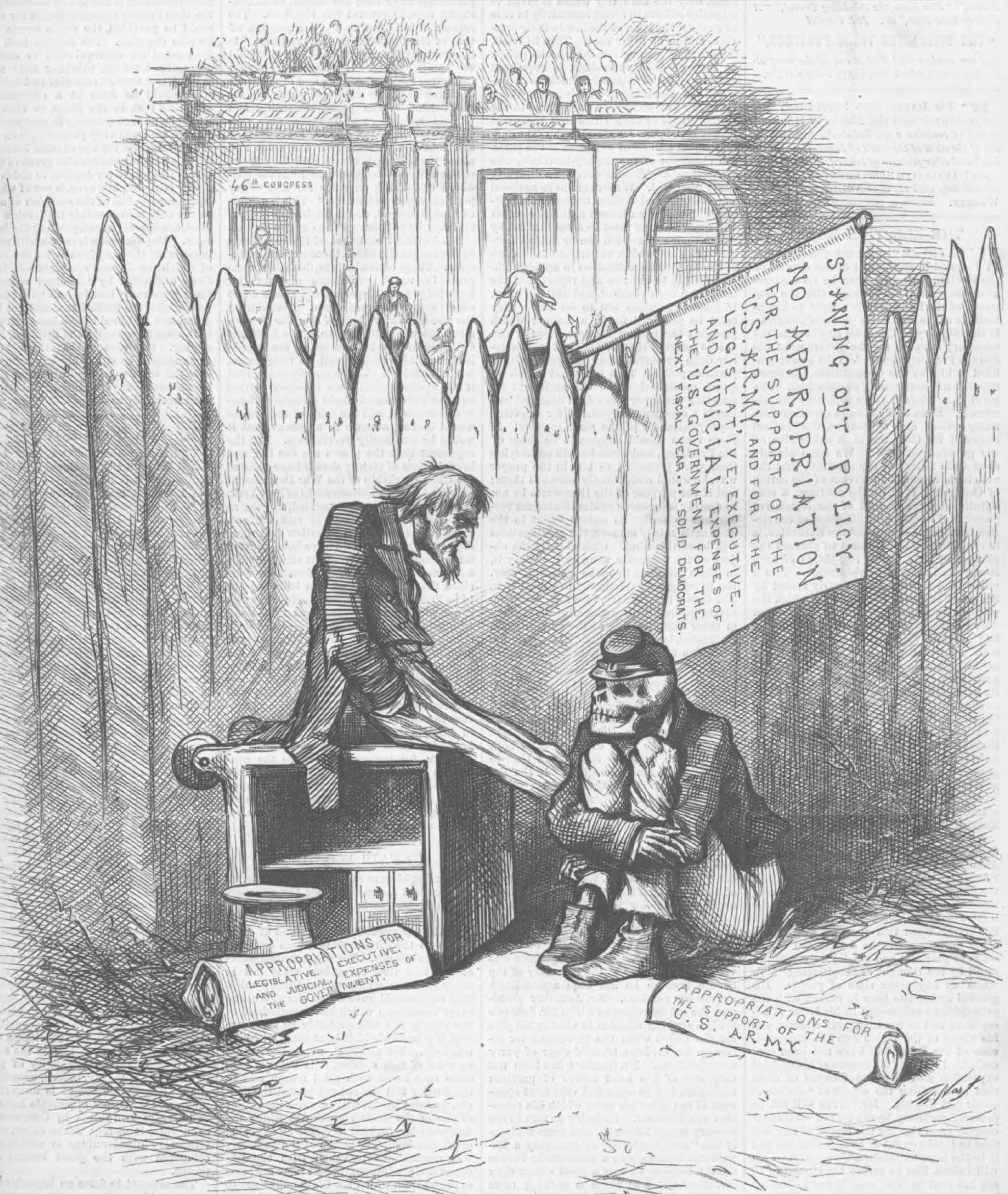

Why does Republican hatred of the professional army in this Civil War era matter to the history of the war? Republican loathing did not, after all, interfere with the success of West Point-trained officers. If the politics of antimilitarism did not change the Civil War’s outcome, they did significantly influence the conflict’s aftermath. While the regular army represented the best tool with which to implement the policy changes prescribed by the Republican party for the nation’s reconstruction, Republican politicians were torn between supporting professional soldiers and reducing military budgets. Once the Republican Party opted to established martial law in the South, with the Military Reconstruction Act of 1867, the regular army took up the role of enforcing Republican Reconstruction edicts. The law divided the former Confederate states (excluding Tennessee) into five military districts, assigned an army officer to each area, and required the commanding general “to protect all persons in their rights of person and property, to suppress insurrection, disorder, and violence, and punish, or cause to be punished, all disturbers of the public peace and criminals.” [4] And yet, just one year later, Republicans in Congress voted to remove nearly 10,000 soldiers from the former Confederacy and permanently reduce the size of the regular force, saving themselves nearly 50 million dollars in the next year’s military budget. Economy clearly came before policy, despite Republican assertations about their goals for Reconstruction—because budgets mattered more to Republicans than Black civil rights. [5]

In his memoirs, John Sherman admitted that, looking back at the war’s earliest days from the vantage point of 1895, he could see that his brother “had a better conception of the magnitude and necessities of war than civilians like myself.” [6] For his part, William T. Sherman spent most of his postbellum career avoiding any political imbroglios, freely and frequently asserting his disdain for politics and politicians. He would never run for office, he famously decreed, and if that fact did not prevent his election, he would never serve. Despite their deep and abiding friendship and their familial bond, the Sherman brothers never reconciled their views on military affairs. Their debate was one shared by many Americans in the Civil War era. And it created no hard feelings between the two men. “The New York papers make out that you and I differ,” William wrote to John on June 26, 1887. To the conqueror of Georgia and the Carolinas the fact was obvious and hardly noteworthy. In the democratic republic that both men worked to save, that was their right: “Of course,” Sherman explained with no hint of bitterness, “we all differ.” [7]

Cecily N. Zander is an assistant professor of history at Texas Woman's University. She earned her Bachelor's degree from the University of Virginia in 2015 and her PhD from Penn State in 2021. She is the author of The Army under Fire: The Politics of Antimilitarism in the Civil War Era (LSU Press 2024).

Image: "'History Repeats Itself'--A Little Too Soon," Harper's Weekly, April 12, 1879

Notes:

[1] Rachel Sherman Thorndike, ed., The Sherman Letters (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894), 121, 116.

[2] Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess., 201.

[3] Congressional Globe, 37th Cong., 2nd Sess., 135.

[4] “An Act to provide for the more efficient Government of the Rebel States,” United States Statutes at Large, 14 Stat. 39, chap. 428, section 3.

[5] Data compiled from Cambridge University Press, Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition online, https://hsus.cambridge.org.

[6] John Sherman, Recollections of Forty Years in the House, Senate and Cabinet, 2 vols. (Chicago: Werner, 1895): 1:245.

[7] Thorndike, Sherman Letters, 375.