Digitizing, Transcribing, and Analyzing the Letters of Rev. J. W. Alvord, Civil War Chaplain and Freedmen’s Bureau Superintendent of Schools

by Gideon French | | Monday, May 15, 2023 - 10:12

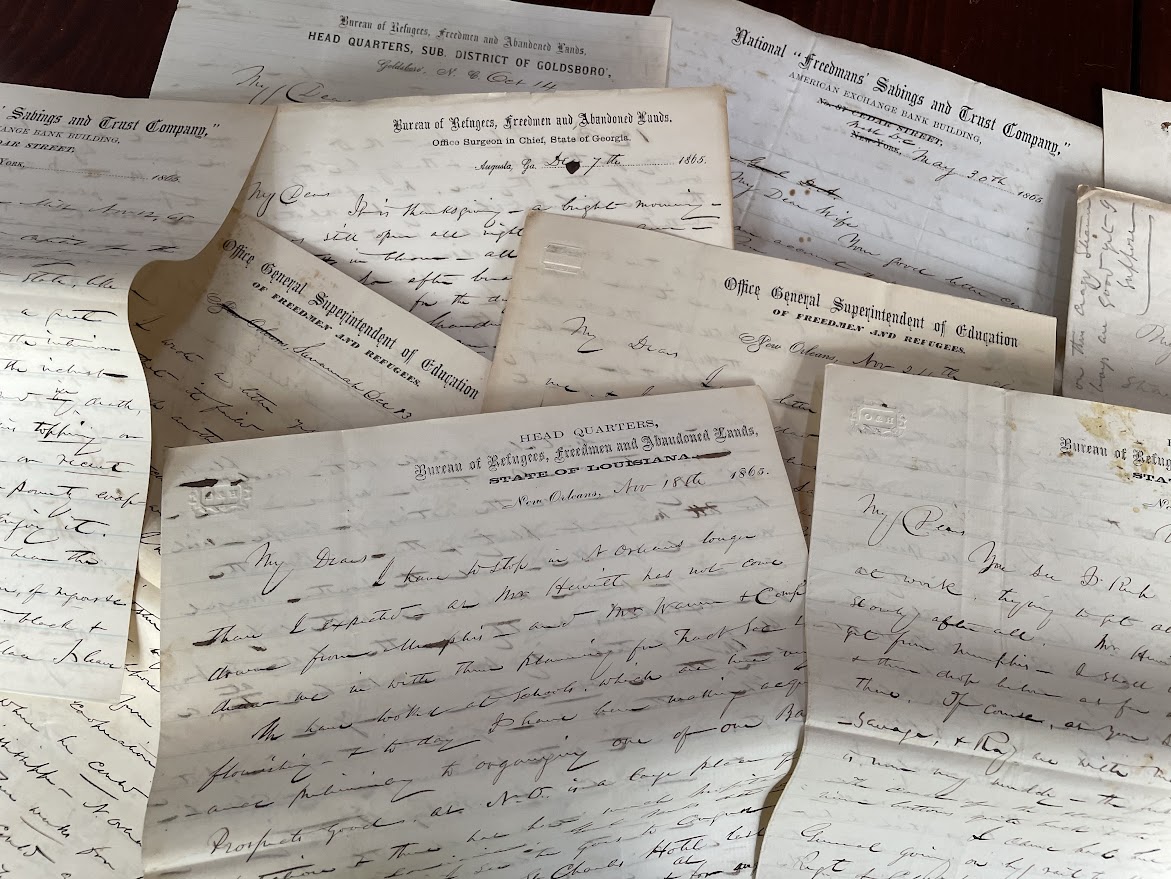

Imagine being given a box of family letters and Civil War artifacts that had been stored for decades in a Florida attic. How would you transform this valuable but long-neglected collection of loose, unsorted letters into archived documents, transcribed text, and data? This was the challenge I faced in Fall 2020. The box contained the private correspondence of Rev. John W. Alvord, a Union Army chaplain who traveled with the Army of the Potomac during its Virginia campaigns and later served as General Superintendent of Schools and Finances for the Freedmen's Bureau and President of the Freedmen’s National Savings Bank.

For the past two and a half years, I have led a team project digitizing, transcribing, and interpreting the writings of Alvord, including nearly 240 private letters authored in the second half of the 19th century. I am now a graduating fourth-year student at the University of Virginia majoring in Computer Science and Statistics, with a minor in History. My interests intersect in the field of Digital Humanities, where I combine science, technology, historical research, and interpretation.

When I received the box, I recognized the historical value of the collection, but the information was untranscribed and inaccessible to the public. To address this issue, I developed and led an interdisciplinary project combining computer science and history, focusing on analyzing these Civil War-era letters using digital humanities tools. As the lead researcher and principal investigator, I secured funding from two sources: a 2021 Jefferson Trust Flash Grant, which covered archival equipment, supplies, and student wages, and a 2022 Harrison Undergraduate Research Award, which supported my textual analysis. I also collaborated with faculty consultants at UVA's Nau Center for Civil War History, the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, and Virginia Humanities.

The project commenced in Spring 2021, during which I attended classes remotely due to the Covid pandemic. Stage one involved scanning, digitizing, and organizing the letters in acid-free folders. In the second stage, conducted on UVA grounds, I hired and trained students to transcribe the letters using FromThePage. Next, I processed[NBC(1] the transcriptions, analyzed the results with statistics and sentiment analysis, and built a website to host the project's results. This website is designed for researchers, teachers, and students to access and use the valuable insights gained from this comprehensive analysis.

The collection currently uploaded to FromThePage contains 233 works, spanning from 1837 to 1883. These letters are authored by more than 36 individuals, with 133 of them written by John W. Alvord himself. In addition to letters, the collection also features passes, poems, notes, sermons, endorsements, minutes, financial documents, copies, and photos. A scrapbook contains additional, unscanned letters, which have not been digitized yet due to the time-consuming manual process involved.

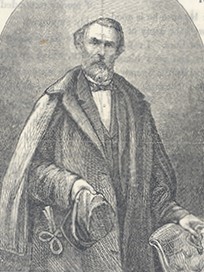

J. W. Alvord

John Watson Alvord was born on April 18, 1807, in East Hampton, Connecticut, to James Hall Alvord and Lucy Cook Alvord. His father was a deacon in the Congregational Church and a staunch supporter of the antislavery movement. Alvord attended the Oneida Institute, a racially integrated college near Utica, New York, which served as a training ground for abolitionists. In 1836, Alvord completed his studies at Oberlin Theological Seminary and was ordained as a minister in the Congregational Church. He served as a pastor from 1836 to 1852.[1]

J. W. Alvord married Myrtilla Mead Alvord on June 3, 1845. Most of the letters are addressed to his wife ("My Dear") or his fellow missionaries. In addition to discussing war and financial issues, the letters often mention his children. He had a total of eight children with Myrtilla, but only three survived past the age of five: Julia Mead Alvord (b. 1847), Samuel Alvord (b. 1857), and John Watson Alvord (b. 1861). Samuel ("Sammy") frequently fell ill, prompting Alvord to try to persuade his wife to move the family south after the war for the sake of his health.

Leaving the quiet life of a pastor behind, Alvord pursued an evangelical mission that took him far from home for extended periods. From 1858 to 1866, he served as secretary of the Boston-based American Tract Society, a non-profit, non-sectarian organization specializing in publishing and distributing Christian literature. The outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861 led Alvord and his fellow Tract Society directors to seek more direct access to soldiers in the field. In Spring 1862, Alvord received permission to accompany General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac during its Peninsula campaign. He kept his fellow missionaries informed of his work on behalf of the Tract Society. When not distributing tracts, Alvord spent much of his time ministering to the wounded and dying. In letters to his wife Myrtilla, he described the chaotic, heart-wrenching scenes that followed the Seven Days Battles (June 25-July 1, 1862). He also traveled with General Oliver O. Howard, a close ally and friend for years to come.

In 1865, Howard appointed him Superintendent of Schools and Finances for the Freedmen’s Bureau. Alvord also served as President of the Freedmen’s National Savings Bank. From Bureau headquarters in Washington, D.C., Alvord traveled south through the former Confederate states of the Atlantic seaboard and Gulf South to establish schools and banks and meet with local officials. His letters, written on Freedmen’s Bureau letterhead, are filled with vivid descriptions of the native Southerners he encountered: sullen, defeated ex-Confederates and newly emancipated, energized African Americans.

Alvord’s Writings

J. W. Alvord’s writings are skillfully detailed with descriptive prose and beautiful use of language. His letters contain discussion of mundane matters such as family finances, work communications, and updates on children and neighbors from his wife. They also are filled with touching fatherly moments where he expressed his deep love for his wife and children, events in the war which shook him to the very core and moved him to tears, and communications with major figures in the war and Reconstruction, including generals and presidents.

Some of Alvord’s most moving and gut-wrenching writings came from his detailing of the horrors of war. In the aftermath of the Seven Days Battles, the culmination of McClellan’s Peninsula campaign which resulted in massive casualties for both Union and Confederate forces, Alvord wrote of burying an unknown soldier: “I helped to bury a poor fellow at midnight last night no shovel, no coffin, we know not his name, nor friends—we only know he was dead—& in this hot climate must be buried at once. It seemed very sad. The bright moon & stars were the only mourners—except the four of us who laid him in the grave—The dust of the soldier boy will not be forgotten by Him who is the resurrection & the life. It was an elegant funeral, as compared with the burial of thousands—hundreds at least out in these forests & over these plains will not be buried at all.” (1862-07-09)

Amid the grim accounts of death and suffering during the low points of Alvord's war experience, he also shared everyday concerns with his wife. While in Florida, he recounted how he filled his pockets and bags with oranges to bring back to his young sons. He composed love poems to his wife, expressing gratitude for her unwavering support even when he was away and through the tragic loss of five of their children over the course of the years due to illness. In another letter, he offered advice to his daughter on how to succeed in her high school exams and admonished her for not being as dedicated and driven as college students. These letters serve as a reminder that even amid the horrors of war, life, love, and family continue to endure.

Scanning and Transcription

One of the early challenges I faced was in scanning these letters. Scanning was complicated by the physical formats of the documents. The letters are different sizes: some are single pages, some are large sheets folded in two, and some are bound in a scrapbook, so a standard format printer scanner would not be able to produce the scans. For the majority of the letters, I settled upon a better solution: a high resolution large format flatbed scanner that was able to scan the images as archival-quality tiffs at 300 to 600 dpi.

The next challenge was finding a way to transcribe the scans. FromThePage, a crowdsourcing transcription platform developed by Sara and Ben Brumfield, seemed like a promising option. FromThePage offered several appealing features. It’s easy for newcomers to learn and use, but it also offers a lot of depth if one chooses to delve deeper. The interface highlights letters that are untranscribed or need review, so transcribers can instantly be paired with a letter to transcribe instead of having to search through to find one. Transcribers can leave notes, underline, italicize, or even format as charts, for spreadsheet-style financial documents. They can also mark the letter for review if they feel that it needs another look, an important feature to enable collaboration.

My Jefferson Trust grant included funds to recruit a team of transcribers. I posted an application and, with the help of the Nau Center, hired six students from diverse academic backgrounds: medical engineering, biostatistics, speech and communication disorders, astronomy, biology, environmental science, and computer science. As none of the students had significant transcription experience, I provided training and support to help them develop their skills. I organized group meetings to introduce the students to the historical letters and the transcription project. I also led peer reviews to ensure accuracy and consistency in the transcriptions, encouraging open communication and collaboration among the team members. I brought on Sue Perdue, Chief Information Officer of Virginia Humanities, to consult and assist in the peer review meetings.

Under my guidance, the students learned to work together to solve problems and share tips, ultimately improving their transcription skills and growing more confident in their abilities. They became deeply invested in the letters and the stories of the families they portrayed. Our team transcribed a total of 10,898 lines of text over more than 250 collective hours of transcription work.

The students exceeded my expectations in their transcription work, becoming highly skilled at deciphering the written content and forming a connection to the stories spanning decades of Alvord's life. At the conclusion of the transcription portion, I asked the students to reflect on what they had learned and what they enjoyed most about the project. One of the students, Anna Dugan, found a family-centered storyline that ran through the Alvord letters to be particularly gripping: “...I followed the story of Alvord’s sickly son Sammy with bated breath. I was relieved to find that Sammy would live to be 29 and have many children of his own.” Paige Hardy wrote that the exchange of letters between the Alvords “was really beautiful and made me think of love back then and today and how that feeling transcends time.”

Multiple students also visited locations that Alvord had written letters from, such as Hilton Head, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia. While they were there, they felt a cross-century connection to him. Becky Williams wrote of their experience: “On Spring Break, when I was in Savannah, Georgia, I stopped to read a historical sign. It turned out to be the headquarters of General O. O. Howard, and I had transcribed a letter that had been written in that very location!” Seeing these students become excited about the letters and even considering doing transcription work in the future was my favorite part of managing the project.

Sentiment Analysis

With transcriptions complete, I turned my attention to the next phase of my research project: a computer-assisted distant reading of the letters using sentiment analysis. I had noticed in my reading and transcription of the collection that the letters varied in mood depending on the period of time and current events. Sentiment analysis uses machine learning and natural language processing to extract the sentiments and emotions of texts. One can assess sentiment for simply positive and negative emotional valence as well as map a variety of emotions expressed in the text, such as anger, anticipation, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, and trust.

Using the Syuzhet sentiment analysis package, I found that the sentiment varied significantly between letters based on context. For example, a letter written in a peaceful period in the 1850s had higher joy and positive sentiment compared to a letter written from the battlefield during the Civil War, which had higher fear and negative sentiment.

A sentiment analysis of Alvord's letters from 1861 to 1865 provides a glimpse into the emotional journey he experienced during the Civil War. The significant peak in positive sentiment on February 7th, 1862, reflects a moment of patriotism, religious inspiration, and professional recognition. In this letter, Alvord's visit to Fort McHenry and his meeting with the president of the American Tract Society, along with the appreciation soldiers showed for his tracts, contributed to his positive outlook. In contrast, the lowest sentiment score from the letter dated March 12th, 1863, highlights the harsh realities of the war. This letter, written as a report for young readers of The Child at Home, reveals the suffering of refugees, starving children, and the desperation of people amid famine. The striking difference in sentiment between these two letters emphasizes the power of sentiment analysis as applied to historical research. Quantifying the emotional content of Alvord’s writings allows us to isolate periods of intense emotion, which can guide us towards a deeper investigation of the surrounding circumstances. Sentiment analysis thus offers not only an emotional overview of the letters but also directs us to significant moments worthy of further scrutiny through close readings. By mapping the sentiment of Alvord's letters against the broader context of the Civil War, we can gain insights into how the conflict impacted him on a personal level.

Next Steps and Goals

My next steps for the project include completing a full sentiment analysis, visualization, and interpretation to better understand the emotions expressed in the letters. I aim to secure future grants to fund more student transcription work to enable a greater understanding of Alvord's life and experiences. All currently unscanned letters, including the bound scrapbook, will be scanned and made available online.

The completion of the website will provide easily accessible hosting for data, transcriptions, images, code, research, visualizations, and educational resources. When the project is fully accessible online, I intend to assist professors and students to integrate the letters into course curriculum and research projects. I also plan to publsih an edited volume of letters, which will highlight the rich correspondence and historical importance of the stories found in the letters. I will also investigate machine learning transcription techniques to improve transcription efficiency and accuracy. The letters will be housed in archives or library collections to preserve them for future generations.

Alvord’s letters are filled with personal anecdotes, reflections on the war, expressions of love for his family, and even details about mundane life events. They provide a nuanced, human perspective on a period that's often understood through the lens of major battles and political events.

What this project has ultimately reinforced to me is the profound power of history to ferry emotion and experiences through time to resonate in our lives today. Digitizing and transcribing Alvord’s letters has done more than simply preserve these historical documents; it has breathed new life into stories previously confined to paper and enabled them to reach a much wider audience. Transcription projects grant access to resources that otherwise might have gone unread and highlight the personal narratives of individuals that are integral to our collective understanding of the past. Transcription democratizes history in a sense, breaking down the barrier of entry to study, learn from, and absorb the past.

This project has demonstrated the crucial role that transcription plays in preserving and disseminating history. By making these letters available online and digitizing the text, we have ensured that they are not only preserved for future generations but also available to a global audience. The digital text can be translated for non-English speakers, shown in different fonts and sizes for accessibility, and transformed into data and visualizations that can give us insights into the past that might not have been apparent otherwise. It has the potential to bring history to a wider audience and make it more inclusive and comprehensive.

Note: All the letter scans and transcriptions from the project are accessible via our FromThePage site at https://fromthepage.com/uvalibrary/letters-of-rev-john-w-alvord. Our full website, which is currently in its beta stage, can be previewed at http://alvordtranscriptionproject.org/. We appreciate any feedback or transcription assistance as we review the transcriptions and add newly scanned letters to the collection. Please feel free to explore the letters and their transcriptions and follow the story of Rev. J. W. Alvord through his writings.

Author: Gideon French is a graduating fourth-year student at the University of Virginia.

Images: (1) Various letters in the collection; (2) From “The Rev. J. W. Alvord's Work in the Army.” 1863, accessed at the Presbyterian Historical Society website, https://digital.history.pcusa.org/islandora/object/islandora:83191; (3) Graph generated in R with ggplot package of sentiment values in letters authored by J. W. Alvord in the collection from 1861 to 1866.

[1] “Alvord, John Watson,” McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia, 2023. https://www.biblicalcyclopedia.com/A/alvord-john-watson.html. Based on The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, James Strong and John McClintock comp. (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1880).