The Civil War caused a national letter-writing boom, as young men rich and poor traveled far from their homes to fight. Many Civil War soldiers were experienced writers. Sons of wealthy plantation families were well-educated and well-read, and they wrote letters peppered with literary references, purple prose, political ideology, and sharp insights into the world around them. Some coped with the lonely hours in camp by writing elaborate love poems to their spouses at home. “I am thinking of thee as I sit here alone / And ponder on days that’s past / And they’ve flown away – like a summer day / Too bright and too happy to last,” wrote Seth Wallace Cobb, a Virginian soldier who later became a U.S. Congressman.

On the surface, the letters from less educated soldiers are less interesting. The Confederate Army’s yeoman farmers and tradesmen wrote about food, furloughs, family, and God. Their letters convey loneliness in stark, simple language. “I want you to take good cear of every thing and do the best you can for I don’t no when I will get to come home,” writes Private Jesse Hill to his wife. “I want to hear from hom that is all the satisfaction we hav here in this dam war” (1864 April 2).

Common soldiers lacked the flair of their wealthier counterparts, but their letters provide a different sort of benefit to the historian. Many low-ranking soldiers were new writers, forced to communicate through the written word for the first time in their lives. They were transitionally literate. They omitted punctuation, changed topics wildly, employed literary conventions sporadically, and often spelled by sound. This unrefined writing provides a valuable record of grammar structures and word meanings that have since become obsolete. And, because the soldiers spelled phonetically, reading their unedited letters allows us to hear not only what they said, but also how they spoke. These inexperienced writers’ phonetic misspellings provide something like an audio recording of the 1860s.

The University of Georgia’s Private Voices project has begun to catalog and analyze these letters. Private Voices has tracked the development of common idioms, identified regional linguistic differences, and made thousands of letter transcripts available to search.

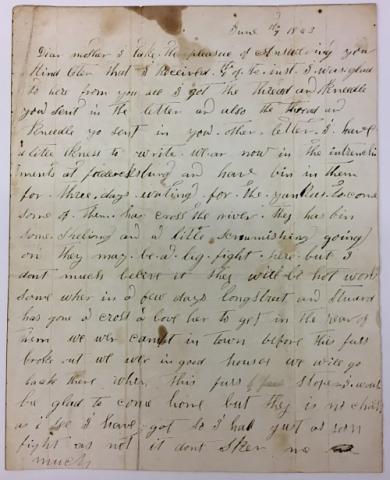

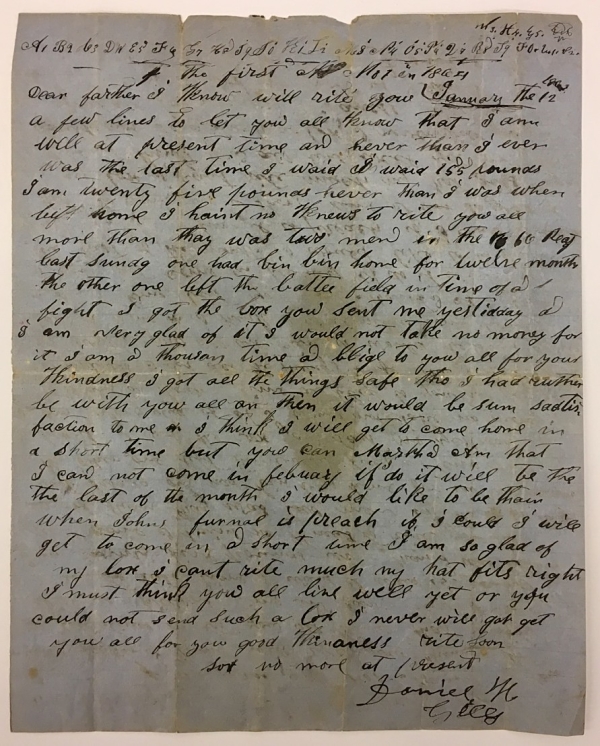

The records in the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (VMHC) add new voices to the corpus under development at Private Voices. One particularly illustrative collection is the correspondence of Private Daniel Haywood Gilley (1838-1911) of Henry County, Virginia. According to the 1850 Census, Gilley’s family were farmers, and his father William owned a parcel of real estate worth just $800. In 1862 Gilley enlisted at Norfolk as a private in Company F of the 16th Virginia Infantry. Later that year he was wounded and captured at the battle of South Mountain before eventually being exchanged. After the war he returned to Henry County, where he is buried. Gilley was an inexperienced writer, but trying his level best to write clearly – he wrote out the alphabet in the margin of one of his letters (1864 November 1). He’d been practicing.

Another soldier in the VMHC’s collection is Private Jesse Hill (1828-1882) of Forsyth County, North Carolina. Hill’s family owned a small farm, valued by Census records at $250. In 1864 Hill enlisted at Wake County, North Carolina in Company K of the 21st N.C. Infantry. Private Voices have nine of Hill’s letters in their database, but the collection at the VMHC contains an additional 33 letters. Like Gilley, Hill was aware of his limitations and perhaps frustrated by them. “I could tel it better than I can rite,” he lamented to his wife (1864 February 5). But Hill wrote frequently, and tried his best to communicate effectively. Gilley’s and Hill’s letters follow many of the linguistic trends identified by the Private Voices project, while also offering exciting insights into the actual sound of the spoken language of the time.

Private Voices has noted a handful of grammatical structures which are no longer in common use but which appear frequently in Confederate letters, including those of Gilley and Hill. Both writers, for example, use “haint” or “hant” as a contraction of “have not” or “are not.” Gilley tells his mother “I wish to rite more but haint got the paper” (1863 June 9), while Hill writes that he “hant missed doing duty yet” (1864 November 26). Similarly, both writers use an a-prefix in ways that modern English does not. Gilley writes about events that are “a going on” around him (1864 May 16), and Hill writes that he “come to the ridgment a new year day” (1864 January 2). Both the have not contraction and the use of an a-prefix are grammatical formulations most common in the South, according to Private Voices’ linguistic mapping.

The soldiers also use words that have shifted meaning since the mid-1800s. For example, both men use the phrase “a heap” to mean “a lot” or “much.” Gilley writes to his mother that he has heard of “a heap of stealing” on the home front (1864 May 16), while Hill reports that “I am a heape tierder than I ever was” (1864 November 1). Hill uses “tolerable” – which he often spells “tolerble” – to mean “somewhat,” a usage that Private Voices has identified as common in the South. Many of Hill’s letters begin with some variation of the phrase “I am tolerble well” (1864 March 16).

The letters also include idioms that are no longer in common use. “I would not be in ther shooes for thir socks,” writes Hill (1864 January 25), saying that he would not want to trade places with a handful of deserters who had been caught. When a member of his regiment is spurned by a lover in a letter, Hill dismissively declares “that is puppy shit in the potomac all such puppy love is puppy shit” (1864 March 30). Of his enemies, Hill writes “I would rather see ther insides than to eat when I am houngry” (1864 April 2).

In addition to illuminating grammar and meaning, Gilley and Hill’s letters are full of phonetic misspellings that show not only how words were arranged in everyday speech, but how individual words were pronounced. These men wrote what they heard, and so Gilley didn’t write gentleman – he wrote “genilman.” Regiment became “ridgment,” particular became “pertichler,” and so forth. The following table shows a collection of interesting phonetic misspellings in Gilley and Hill’s letters at VMHC.

|

Modern spelling |

Gilley and Hill’s spelling |

Citation |

|

Aggravate |

agervat |

Hill, 1864 April 30 |

|

Alfred |

Alferd |

Hill, 1864 January 2 |

|

Battlefield |

batle feel |

Gilley, 1864 June 16 |

|

Borrow |

bory |

Gilley, No year, April 27 |

|

Cold |

cole |

Gilley, 1864 March 28 |

|

Colonel |

Connol |

Gilley, 1864 March 28 |

|

Confederacy |

confedercy |

Hill, 1864 April 30 |

|

Confederate |

conferet |

Gilley, 1862 July 13 |

|

Damnedest |

damdis |

Hill, 1864 February 7 |

|

Darned |

durnd |

Hill, 1864 February 5 |

|

every day |

ever day |

Gilley, 1864 September 12 |

|

Factory |

facory |

Gilley, 1864 May 16 |

|

Father |

Farther |

Hill, 1864 February 9 |

|

Forward |

faward |

Gilley, 1864 May 16 |

|

Funeral |

funel |

Hill, 1864 June 8 |

|

Gentleman |

genilman |

Gilley, 1864 September 4 |

|

have not |

haint |

Gilley, 1863 June 9 |

|

much obliged |

much a blege |

Hill, 1864 December 4 |

|

Neighborhood |

neighood |

Gilley, No year, April 27 |

|

Officers |

offerssers |

Hill, 1864 April 30 |

|

Ought |

ort |

Hill, 1864 June 10 |

|

Particular |

pertichler |

Hill, 1864 October 2 |

|

Potatoes |

taters |

Hill, 1864 February 7 |

|

Prisoners |

presners/prisners |

Hill, 1864 February 7 |

|

Provision |

pavishion |

Hill, 1864 April 30 |

|

Rather |

ruther |

Gilley, 1864 November 1 |

|

Regiment |

ridgment/redgment |

Hill, 1864 January 2 |

|

Representative |

Repesenteve |

Gilley, 1864 March 28 |

|

Satisfaction |

sadfaction |

Gilley, 1862 August 3 |

|

some time or other |

some time a nother |

Hill, 1864 October 25 |

|

sort of |

sorty |

Hill, 1864 June 10 |

|

Suppose |

surpose |

Gilley, 1864 June 16 |

|

There |

they |

Gilley, 1864 September 12 |

|

Vegetables |

vegables |

Gilley, 1862 July 13 |

|

Virginia |

Vaginia |

Gilley, No year, April 27 |

|

Yesterday |

yestiday |

Gilley, 1864 September 12 |

The letters are filled with other spelling errors, but seeing “news” spelled as “nuse” (Hill, 1864 December 1) or “knews” (Gilley, 1864 September 12) doesn’t shed any light on how the words were actually said, unlike the entries in the table. Only words that have been misspelled because of their conversational pronunciation have been included. The effect of the misspelling is especially pronounced when a sentence is constructed from the words in the table. “The durnd Conferet offerssers ort not to agervate this pertichler Vaginia ridgment,” Hill might have said. It’s a dialectic transcription that would have made Twain or Faulkner proud. The soldier’s accent comes through clear as day.

These letters from transitionally literate soldiers provide a detailed record of the structure and sound of nineteenth-century colloquial English in a way that documents from more refined writers do not. Gilley’s and Hill’s letters are the rare historical objects that exist in two dimensions – they can be seen and they can also be heard. They offer modern scholars a remarkable opportunity to hear the voices of the Civil War as they would have actually sounded.

Ben Hitchcock is a fourth year undergraduate majoring in Creative Writing and Foreign Affairs. Ben spent summer 2018 as an intern in the archives of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, studying the correspondence of Confederate Civil War soldiers.

Images: Letters of Daniel Haywood Gilley, June 9, 1863 and November 1, 1864 (courtesy Virginia Museum of History and Culture).

Works Cited:

Berry, Stephen, Michael Ellis, Michael Montgomery. Private Voices, Center for Virtual History, University of Georgia, 2017. https://altchive.org/private-voices/

Cobb, Seth Wallace. “Letter to Victoria A.M. Davidson Farrar, 1863 October 14, Richmond, Va.” Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

Gilley, Daniel Haywood, Letters, 1862-1865, Virginia Museum of History and Culture, n.p.

Hill, Jesse, The Letters of Private Jesse Hill, Virginia Museum of History and Culture, n.p.