Working for Mount Vernon this summer is one of the experiences whose pivotal importance I recognized from the outset. I remember receiving the first email with the formal introduction and a very brief description of the projects I would be tackling: transcription & research. I had done both tasks before but I was aware they took on a different connotation since I would be working for the first time in a major institution such as Mount Vernon. Soon I started to slightly worry whether I was qualified enough to do the job correctly, but the moment I talked to my supervisors, Jeanette Patrick and Jim Ambuske, whatever preconceptions or apprehensions I had vanished. They clearly laid out their expectations, delivered precise instructions for my two major projects, and reassured me that if I had any questions I could always reach out to them. Thanks to their clarity and confidence in me, I was able to begin my first day without hesitation clouding my work.

Learning about George Washington and the world around him represents a natural start for any type of internship in Mount Vernon. Ms. Patrick procured a copy of You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington, which she also had delivered to me. I even had the pleasure of being present in a group call in which the author, Alexis Coe, talked about her approach to history and methodology. Another important aspect of this introductory period was understanding the world around Washington, which meant acquiring knowledge of the enslaved people living in the estate whose forced labor made Washington’s luxurious life possible. For that topic, I read a few chapters from “The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret”: George Washington, Slavery, and the Enslaved Community at Mount Vernon written by Mary V. Thompson, the Research Historian at Mount Vernon. This reading was more emotionally challenging, since it tackled the difficult subject of slavery. But it enabled me to better comprehend the life of an enslaved person and helped me situate the place where I was going to work as a site founded on inequality and built by unfree hands. Both readings helped me familiarize myself with the history of the house, its owner, and the people who lived in it and around it. Once the first two weeks expired, I began working on my projects in earnest.

My first major project consisted of transcribing John Augustine Washington III’s correspondence between 1838 and 1861, which I accessed on the Digital Collections website belonging to the Washington Library. Mr. Ambuske sent me a workflow detailing transcription conventions and other general notes that were easy to understand. Thanks to my extensive experience working with manuscripts at The Washington Papers, I was able to complete my first task promptly. More than just transcribing, actually reading through the manuscripts provided me with a unique insight into the period. In one letter from the 1840s, Joseph McFarland wrote to John Augustine Washington about how “times is very different to what they was,” as if already there was an emerging consciousness in the antebellum South acknowledging the coming of a new age. The Civil War is a topic I normally encounter in the comfort of academic books or papers, but reading about the tangible economic consequences of war grounded the conflict in reality. Several letters contained the address “Charlottesville, Albemarle County,” since John Augustine Washington studied at the University of Virginia. Details like those lent humanity to my work. In fact, the process of familiarizing myself with the handwriting of certain people and then becoming involved in the microcosm of their world, it felt as if I was establishing a direct connection to a distant past. The entire transcription process became surreal in a certain way, once I became comfortable enough to recognize the person just by looking at the letter.

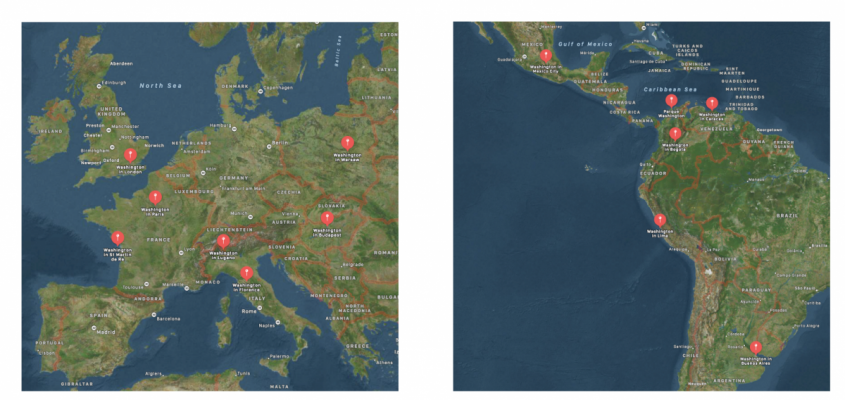

My second major task could not have been more different. I pivoted from reading manuscripts to becoming a globe-trotting detective. My work laid the foundation for the upcoming George Washington Commemorations Project, whose goal is to assemble a database of Washington commemorations from throughout the world. At first, I looked for commemorations in the United States put up between the 1850s and the 1870s. I used an array of methods that varied in complexity and formality. I looked at the National Register of Historic Places as a starting point, and I changed course by searching for local websites that talked about their monuments. My research method even included typing “George Washington” on Google Maps. As expected, there were not many George Washington monuments put up in the mid-1850s. Washington declined in popularity during those years, and wartime often stresses economies and makes expensive artistic projects unfeasible. The statues I did find from the era usually used Washington as a unifying figure to promote nationalism in a time of intense fragmentation. Once my exploration of the United States hit a plateau, I shifted my focus onto the world. I found out George Washington can be found in the most confusing and fascinating of places. Washington stands on Virginian soil in London’s Trafalgar Square, right at the heart of the United Kingdom. Washington’s bust rests on the shores of Switzerland, where it gazes into the stillness of an Alpine lake. Washington even has two different statues in Colombia alone. He has several names depending on where you look for him: Jorge, Jerzy, Georges, Giorgio. For this task, I took advantage of my familiarity with different languages to read the various local histories behind the Washington commemorations.

Aside from reading manuscripts and checking the coordinates of Washington statues, I spent a considerable amount of time listening to and learning about podcasts. My supervisors run the Conversations at the Washington Library podcast as well as the Digital Book Talk series. Hilde Perrin (a wonderful colleague from Washington College who was working on a project about early American music) and I even sat in on a live recording of an upcoming podcast episode, and we helped produce a Book Talk live-stream by writing down audience questions. These were incredible real-world experiences that provided me with priceless knowledge about podcasting and live-streaming. For the first time, I could see legitimate historical research being presented in digital mediums like podcasts or live-streams, outside of the traditional paper/book format. I sincerely hope that in the future, history as a field will continue to embrace digital avenues as valid options for historians to present their work. History must evolve and exist beyond the confines of the written word.

After working for Mount Vernon, I’ve emerged from this internship with a renewed awareness of history. Prior to this internship, my understanding of history was limited to reading texts in a classroom and researching various research questions at The Washington Papers. Now I understand there are a myriad of ways to do history. I’ve learned that history can transcend different mediums, from books to public live streams on Facebook to bronze statues. I have come to appreciate how history is a collaborative subject, in which I can work with people in the present to create a podcast or create relationships with people in the past by reading their letters. And as a result, I have gained a more open vision of what a career in history looks like. From producing to transcribing, history has much to offer for people with very different skills. I owe my new insight into careers in history not only to my work but also to the many chats I have had with the incredible people working in Mount Vernon – archivists, architectural historians, archaeologists, exhibition curators, just to name a few. The experience and knowledge I have acquired throughout this internship are invaluable, and I will remember this as one of the formative periods of my career as a historian.

Images: (1) Samanta M. Pomier Jofré at Mount Vernon, (2) Map of George Washington monuments in Europe and South America