The Civil War left Pennsylvania lawyer and UVA alumnus James Shunk bitter and angry. In the late 1850s, as a federal secretary and clerk, he had championed the “permanency of the Union” and worked to hold the country together. When the war erupted, he denounced the Confederate “rebellion” and briefly enlisted in the Union’s defense. As a conservative Democrat, however, he vilified his Republican rivals, accusing them of provoking the war, defying the Constitution, and destroying the antebellum racial order. By 1865, with society transformed and slavery crumbling, Shunk feared that the Union he had hoped to save—“the Union as it was”—no longer existed.

During the war, Republicans decried Shunk and his Democratic allies as traitorous Copperheads, insisting they would “carry Pennsylvania into the Southern Confederacy.” For more than a century afterward, historians often followed course, portraying Civil War-era Democrats as southern-sympathizing obstructionists. In recent years, however, scholars have begun reassessing the party’s convictions and its contributions to the Union war effort, by charting the range of opinion and the internal divisions among Democrats. Democrats in the party’s “peace” faction were deeply conservative, bitterly racist, and scornful of Lincoln’s conduct of the Union war effort. Democrats in the party's pro-war majority, while critical of Republican policies, were strongly committed to the overarching cause of restoring the Union, and, as they saw it, to preserving constitutional liberty. Shunk’s career illustrates how extreme Democrats wielded power within the party, couching their deep animus against Lincoln and emancipation in a rhetoric of restoration and loyalty.[1]

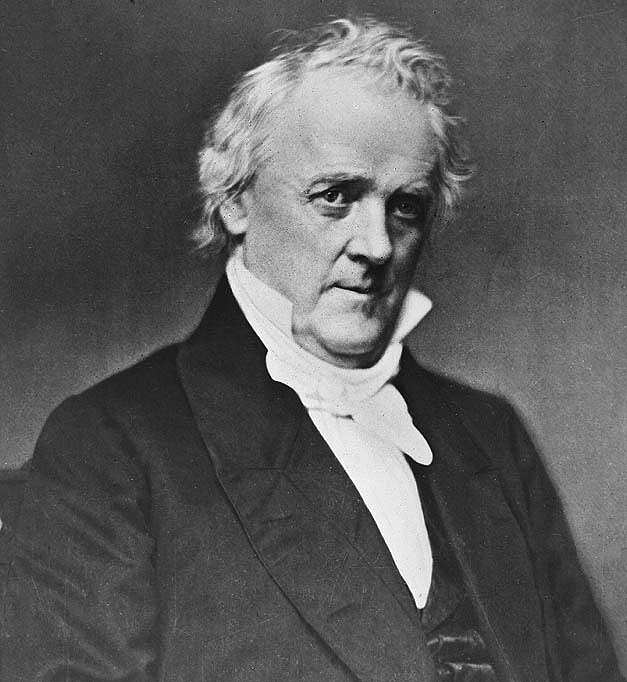

James Findlay Shunk was born on April 18, 1836, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, into an influential Democratic family. His grandfather William Findlay was a governor and United States Senator, and his father Francis R. Shunk served as governor from 1845 to 1848. James attended Harrisburg Academy before enrolling at the University of Virginia, where he spent the 1854-1855 academic year studying law and modern languages. He followed his father into the Democratic Party, and in the spring of 1857, Jeremiah S. Black—Attorney General under President James Buchanan—appointed him to a clerkship in his office. Shunk solidified their political alliance by marrying Black’s daughter Rebecca on March 10, 1858.[2]

Pennsylvania editors hailed Shunk as a rising star in the state’s Democratic Party, and by 1859 he had secured a spot on the State Central Committee. That December, the committee condemned Republicans as abolitionist fanatics and blamed them for John Brown’s “bloody and treasonable invasion” of Virginia. They warned that the election of 1860 could decide the “issue of Union or disunion,” and they cast Republicans as a “sectional and incendiary organization.” The “National Democratic party,” by contrast, claimed to defend the Constitution and the “equality of the States.” Shunk and his allies affirmed the Supreme Court’s pro-slavery Dred Scott decision, upheld the fugitive slave law, and declared that every state had the “sovereign right” to “maintain its own domestic institutions.” They prayed that the “Conservative Commonwealth” would rally to their cause and ensure the “permanency of the Union, the triumph of law, and uninterrupted prosperity of the nation.”[3]

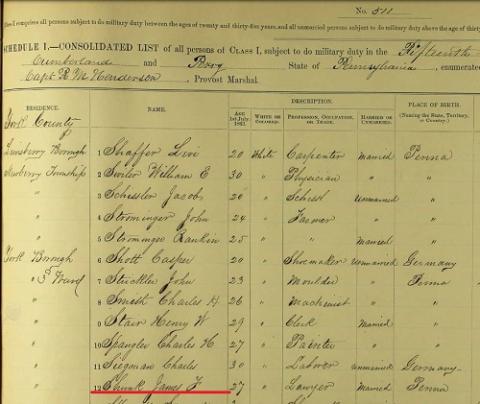

When the Civil War began, one of Shunk’s brothers enlisted in the Union army, while another became a clerk in the State Department. Shunk, however, settled in York, Pennsylvania, and opened a law practice with his father-in-law. Then, in September 1862, Confederate General Robert E. Lee marched into Maryland, hoping to resupply his army and damage northern morale. The governors of Maryland and Pennsylvania called for short-term volunteers to meet the emergency, and Shunk enlisted on September 12, 1862. He spent the next twelve days as a private in Gibson’s Infantry Company, a local home guard unit. Lee’s army returned to Virginia after the Battle of Antietam, and Shunk mustered out of service on September 24 without ever seeing combat.[4]

Although Shunk opposed the Confederate “rebellion,” he became increasingly frustrated by Republicans’ wartime policies. At a “monster mass meeting” in September 1863, he denounced Lincoln as a tyrant, observing that the “mere will of the President avails to strip the citizen of [his] securities.” To meet the challenges of war, Republicans had passed a national conscription law, suspended habeas corpus, censored and imprisoned some critics, and proclaimed a policy of emancipation. Shunk viewed these wartime measures as an assault on constitutional freedom, and he accused Republicans of waging a remorseless, “Satanic” struggle. The “fields which in Democratic days were mellow with harvests,” he insisted, were “in this Abolition millenium [sic], red and soaked with the blood of the reapers.”[5]

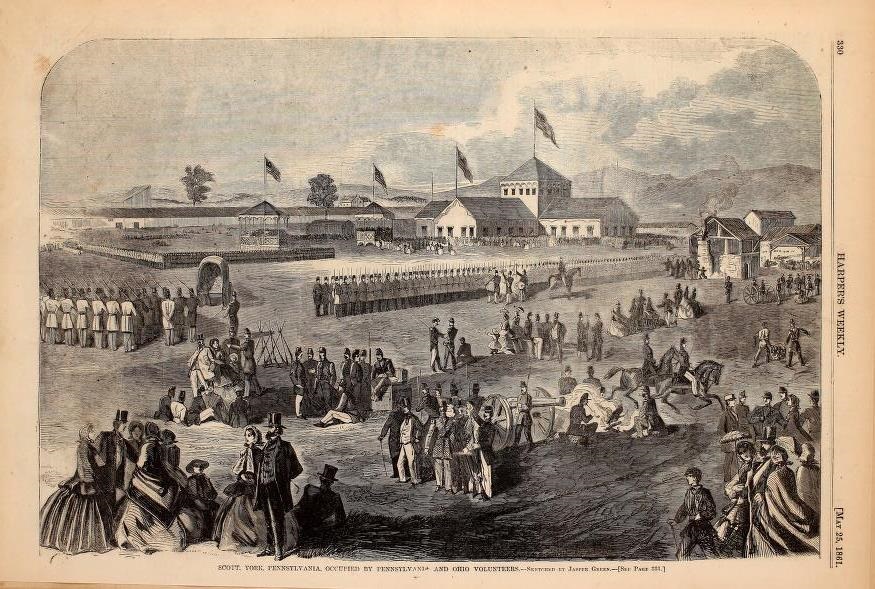

When Republicans condemned conservative Democrats as “Copperheads” and “traitors,” Shunk vehemently defended his party’s patriotism. For decades, he claimed, Democrats had struggled to “maintain the integrity of the Republic.” The “Policy of our party saved the Union while it lasted—[and] that policy only can restore it.” He noted that many Union generals were Democrats, including former General-in-Chief George McClellan—“the hero of Antietam” and the “idol of the people.” With Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial election approaching, Shunk endorsed conservative judge George Woodward. Republican Governor Andrew Curtin, he observed, had twice “allowed” Confederate armies to invade the state. Woodward, however, would “hurl back the invader,” ensure the “return of peace,” and restore the “Union under the Constitution.”[6]

In 1864, Shunk served as a delegate to Pennsylvania’s Democratic State Convention, where he helped nominate McClellan for president. The delegates offered no specific platform, instead praying that the party’s national delegates would craft a “declaration of principles acceptable to all the States.” They urged Democrats across the country to come together, declaring that the “welfare and prosperity of the American Republic” depended upon their party’s victory. Only by removing the “present corrupt Federal Administration,” they argued, could Americans “bring back peace and union to this distracted land.”[7]

The Union armies’ triumph, however, did little to relieve Shunk’s anxieties. In November 1865, with slavery collapsing and Reconstruction underway, he delivered a bitter, racist tirade against Republican rule. Radical Republicans hoped to ensure the Union’s survival by empowering African Americans and disfranchising former Confederates. Shunk, however, viewed these policies as a violation of the social order. He accused Republicans of destroying the Constitution, stifling dissent, and imposing unjust terms on the South. Their vision for Reconstruction, he insisted, closed the “gates of the Union on the States which are seeking in good faith to return.” Shunk, by contrast, sought to restore the “Union as it was”—readmitting the southern states, pardoning Confederate soldiers, and preserving racial hierarchy.[8]

Shunk served as editor of The Easton Argus from 1869 and 1872, and he used it to articulate this conservative political vision. He championed civil service reform, government retrenchment, and religious freedom. He also mocked and derided African-American Congressmen, accused freedmen of “barbarous idolatry,” and declared Abraham Lincoln an “unregenerate man” unworthy of memorialization. As late as 1871, he fiercely critiqued Republicans’ wartime policies. He argued that General Philip Sheridan had “mercilessly burned” the Shenandoah Valley, leaving a “record of destruction more ruthless” than anything in “all the history of the world’s wars.”[9]

Shunk sold his interest in the Argus in 1872, but he remained a “constant contributor” to the state’s newspapers. He died of heart disease in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on January 20, 1874, at the age of thirty-seven. Mourners hailed him as a “brilliant writer” and a “master of English literature”—but they also testified to his rabid partisanship and the “exceeding bitterness to which his pen was naturally given.”[10]

Shunk’s life underscores the persistence, among Democrats in the Civil War North, of an old tradition of proslavery Unionism, one that had rendered Northern Democrats subservient to Southern interests before the war and that presented a formidable obstacle to reconstruction and to real change afterwards. In 1870, for example, Democrats in York, Pennsylvania declared themselves the “White Man’s Party” and vowed to “save the Government” by “prevent[ing] the entire degradation of the white race.” Shunk concurred, explaining that his party defended the Constitution “as a heritage for white men and their children.” The demise of Reconstruction resulted not only from the waning commitment and “retreat” of its Republican supporters but also from the active opposition and hostility of Northern Democrats such as Shunk.[11]

Images: (1) Civil War Draft Registration Card for James F. Shunk (courtesy Ancestry.com); (2) James Buchanan (courtesy Library of Congress); (3) York, Pennsylvania, During the Civil War (Harper’s Weekly, May 15, 1861).

[1] The York Gazette, 29 September 1863; Jack Furniss, “States of the Union: The Rise and Fall of the Political Center in the Civil War North” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 2018), 10. See also Joel Silbey, A Respectable Minority: The Democratic Party in the Civil War Era, 1860-1868 (New York: Norton, 1977); Jean Baker, Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Michael Todd Landis, Northern Men with Southern Loyalties: The Democratic Party and the Sectional Crisis (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014).

[2] William Henry Egle, History of the Counties of Dauphin and Lebanon in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1883); Catalogue of the University of Virginia: Secession of 1854-55 (Richmond: H. K. Ellyson, 1855); The Valley Spirit (Chambersburg, PA), 17 March 1858; The Pittsburgh Daily Post, 2 June 1857.

[3] The Democrat and Sentinel (Ebensburg, PA), 4 January 1860.

[4] The Sacramento Bee, 22 February 1861; The York Gazette, 7 January 1862; William Marvel, Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 123); The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, Vol. 4, ed. Frank Moore (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1862), 354); “James F. Shunk,” U.S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865, available from ancestry.com.

[5] The York Gazette, 29 September 1863.

[6] The York Gazette, 29 September 1863. Republicans accused Woodward of disloyalty. As historian Jonathan White explains, however, “Woodward’s allegiance to the nation never faltered,” and his wartime correspondence “reveals the convictions of a Democrat who strove to be loyal amid constant accusations of treason.” See Jonathan W. White, “A Pennsylvania Judge Views the Rebellion: The Civil War Letters of George Washington Woodward,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 129, No. 2 (April 2005), 195-225.

[7] The Valley Spirit (Chambersburg, PA), 30 March 1864; The Pittsburgh Daily Post, 19 March 1864.

[8] The Bedford Gazette, 5 January 1866.

[9] The Luzerne Union (Wilkes-Barre, PA), 3 March 1869; The Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, PA), 13 November 1871; The Morning Star and Catholic Messenger (New Orleans, LA), 23 July 1871; The Clearfield Republican (Clearfield, PA), 19 July 1871; The Columbian (Bloomsburg, PA), 24 February 1871; The Jeffersonian (Stroudsburg, PA), 26 December 1872; The Perry County Democrat (Bloomfield, PA), 6 April 1870; The Edgefield Advertiser, 1 September 1869; The Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, PA), 31 August 1867.

[10] The Jeffersonian (Stroudsburg, PA), 26 December 1872; The Valley Spirit (Chambersburg, PA), 28 January 1874; The York Gazette, 27 January 1874; The Perry County Democrat, 28 January 1874; The Intelligencer Journal, 21 January 1874.

[11] The York Gazette, 19 July 1870; The Bedford Gazette, 5 January 1866.