The Union capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina in January of 1865 was a major blow to the reeling Confederacy and set the stage for Lee’s surrender four months later. Black Virginians in Blue were among the USCT soldiers who landed that blow.

As it was the Confederacy’s last major port on the eastern seaboard, the defense of Wilmington, North Carolina, was essential to the Confederate government’s very survival. Blockade runners departing from the Wilmington’s docks sailed south on the Cape Fear River and into the Atlantic Ocean, bound for international ports in Bermuda, England, Canada, and the Caribbean. This allowed the Confederacy to maintain links to the outside world, exchanging cash crops like tobacco and cotton for vital wartime necessities.

The Confederates enacted an elaborate defensive strategy at the beginning of the war, anchored by the massive Fort Fisher south of the city. The fort had been constructed with a mountain of earth and sand to better withstand and absorb Union shelling; furthermore, guns facing the ocean allowed its defenders to prevent Union ships from entering the Cape Fear river and advancing on the city itself. By early 1865, a variety of attempts by Union forces to penetrate the Carolina interior and seize the port had failed. Following General Benjamin Butler’s failed expedition in December 1864, Major General Alfred Terry led a new expedition in January 1865 with 9,000 northern troops dispatched from the Army of the James at Petersburg, Virginia. Like many commanders at the time, Terry was hesitant to use black troops in combat. Upon their assignment to his expeditionary force, he complained to an aide, “we want white men here.” When combined with Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s blockading squadron consisting of nearly 60 vessels, Terry’s force sought to destroy the fort and capture Wilmington at long last.

Included in Terry’s Provisional Corps were fifteen members of the United States Colored Troops who originally hailed from Charlottesville or Albemarle County, Virginia. These “Black Virginians in Blue” included: Joseph H. Thomas, John M. Winfrey, William Page, John H. Hopkins, John Hailstock, Nelson Means, Thomas Walker, Thomas Gibson, Nimrod Goins, Lewis L. Winfrey, Edward Rollins, Isaiah Reed, Daniel Fossett, William Harris, and William Spears.* United under the command of Brigadier General Charles J. Paine’s XXV Corps (Third Division), these men contributed to one of the most courageous and daring operations of the entire war.

This essay will focus on Edward Rollins, who along with comrades-in-arms such as Nimrod Goins, Joseph H. Thomas, Daniel Fossett, and Isaiah Reed, was born in Albemarle County, a major slaveholding county in Virginia, yet managed to reach freedom west of the Appalachian Mountains in Ohio. The Buckeye State had one of the largest black populations in the North throughout the nineteenth century, witnessing a constant stream of migration from surrounding border states of the upper South to rural townships and small villages in southern Ohio. Most of these black migrants were Virginians.

While slavery was not legal in Ohio, the rights of African Americans were still severely limited in scope. Despite this, blacks faced relatively better conditions than they could expect in the bordering slave states of Kentucky and Virginia; abolitionist movements underway at local colleges and in large cities in Ohio combined to create a uniquely tolerant atmosphere. For example, Oberlin College became the first institution of higher learning in the nation to admit black students to a predominantly white university in 1835. The appeal of Ohio compelled many families to migrate there or to flee slavery on the region’s underground railroad, seeking refuge and greater economic, political, and social opportunities.

One such man from Albemarle was Edward Rollins (Rollans), born on March 16, 1836, in Charlottesville. At some point before the war, Rollins moved to a farm near Frankfort in Ross County, Ohio. Rollins worked as a farmer. His first wife, Mary Stewart Rollins, died in 1857, presumably in Ross County.

Rollins, a free man, enlisted as a private at the age of 28 on August 15, 1864, in Delaware County and mustered in on August 25 in Hillsboro. His service record describes him as 5 feet, 5 inches tall, with black hair, black eyes, and dark complexion. He served in Company A of the 5th USCT Infantry Regiment. Rollins served with the 5th for a term of one year, mostly in Virginia. Rollins saw action at Deep Bottom, and was wounded in action, most likely at Fort Gilmer on September 29, 1864. Although there are conflicting testimonies of how he was wounded, it seems that he was hit with a piece of shell in his left knee. He was treated in a field hospital or a US hospital boat at Fortress Monroe, Virginia after his injury. Along with his comrade, Reed, Rollins was transferred to North Carolina in December 1864.

Terry’s expeditionary force approached Fort Fisher on January 12, 1865, with nearly 9,000 troops at his disposal. The next day, Union gunboats under Admiral Porter began shelling the beach north of the fort, where two hundred boatloads of troops soon landed unopposed. Once ashore, Terry immediately began efforts to reinforce and strengthen the beachhead. Paine’s division, consisting of the USCT troops, was ordered to construct a defensive line north of the fort to protect against an attack by Confederal General Robert Hoke’s division of approximately 6,000 troops stationed at the northern end of the Sugar Loaf peninsula. Not wanting to risk opening the route to Wilmington and the city’s capture, Hoke and the Confederate commander in the region, Braxton Bragg, decided to keep Hoke’s division unengaged and did not attack the vulnerable USCT troops.

Upon the establishment of the beachhead, a powerful bombardment commenced. Dixon’s fleet bombarded the fort for nearly two days, knocking many of the Confederate big guns out of action. Union forces next launched a two-pronged attack, one by a naval contingent of approximately 2,000 personnel and another land-based approach by the white units under Terry’s command. In brutal fighting that eventually devolved into hand-to-hand combat, the Union troops soon stalled, prompting the insertion of USCT reinforcements. Men of 27th USCT regiment, including Daniel Fossett, along with other reinforcements from Terry’s command, begin preparing to launch the final assault on the fort at approximately 7:00 p.m. Fort Fisher’s downfall was near as the men of the 27th catapulted over the parapets and into the fort, where the last rebel defenders eventually withdrew south; the fort was captured near 10:00 p.m. when her guns fell silent. At the same time that the 27th USCT was engaged inside the fort, the other USCT regiments, including Edward Rollins’s 5th USCT, held off a feeble final attempt by Hoke to save the fort. For the Confederates, it was too little, too late–the fort was in northern hands.

The sunrise on January 16 brought with it a hellish glow that illuminated the battlefield. The wreckage of the previous few days littered the battlefield, with nearly 1,000 Union casualties and almost double the number of Confederate casualties. The loss of Fort Fisher was especially compromising for the city of Wilmington, the last remaining major seaport under Confederate control. Cut off from global trade markets, the Confederacy now stood alone with regards to supplies; the loss of the fort proved devastating to the Confederate war effort, as starved commands like General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were unable to access vital food stores. A month later, when the city of Wilmington itself fell, the last bit of hope for the South–potential European recognition–was muzzled with the closing of the port.

Edward Rollins remained in the army through that summer, when he mustered out on August 29, 1865, in New Bern, North Carolina, due to the end of his one-year term of service.

Following the war, Rollins, returned to Ohio just like many other “Black Virginians in Blue” such as Goins, Thomas, Fossett, and Reed. He worked as a barber and a janitor in Fayette County. He married his second wife, Martha C. Gray Rollins, a year or two after his discharge from the army. Together they had one daughter, Nellie Rollins Ryans, born on August 27, 1871. Martha died on July 7, 1877. Rollins then married his third wife, Anna Davis, whom he later divorced prior to her death in 1887. Together they had a son, Clifford Rollins, born on October 7, 1883. After his service, Rollins suffered from rheumatism, piles, deafness, disease of the heart, urinary organs, stomach, head, breast, kidneys, and rectum, as well as chronic diarrhea and general debility. Fortunately for Rollins, he was able to obtain and to draw on a pension of $6 per month beginning in 1894. This was increased several times for the remainder of his life, peaking at $20 per month in 1911. At the time of his death, he was living with his daughter in Bloomingburg, suffering from illness for four weeks. He died of old age and senile debility in Bloomingburg on January 26, 1912.

For the Union, the capture of Fort Fisher was the final nail head on a coffin that the northern war effort had spent four years constructing. Rare in the context of the Civil War, the hand-to-hand combat at the fort was perhaps some of the most desperate fighting that many of the men present ever experienced. Fifty-four Union servicemen would receive the medal of honor for their actions at Fort Fisher, including one African American soldier.

In addition to their shared experience at Fort Fisher, these Black Virginians in Blue who originally hailed from Albemarle County and subsequently moved to Ohio are a fascinating case study of USCT troops whom have been counted as “Northern” in tallies of the origins of black regiments, despite their Southern roots. Ultimately, approximately 5,000 Ohio blacks served in state or federal units during the Civil War—and we can extrapolate, based on the Albemarle example, that many others of these Ohio men had fled slavery or migrated from slave states.

Though blacks still composed less than 3 percent of the total population of Ohio, over the course of the 1860s their numbers increased by 72 percent (from 36,673 to 62,213), an unprecedented gain that far outpaced any other state. The Buckeye State went from ranking fifth among northern states in the size of its black population and third in percentage of blacks in its total population, to ranking second in both categories in 1870, respectively. Like earlier migrants to Ohio, post-war black migration had the primary destination of the countryside where blacks already lived; nearly 50 percent of the black population increase occurred in rural townships. Likely driven by a strong incentive to settle quickly in familial settings, these African Americans were able to assimilate into preexisting agrarian communities. Since many whites served in and were eventually incapacitated or killed by the war, the demand for seasonal farm labor remained unusually high in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War; thus, the return of these Black Virginians in Blue is not surprising given this trend as well as their pre-conflict residency.

The final capture of Fort Fisher—a key goal that long eluded the Union forces—was a major feat. The Union's victory there is a testament to the resolve of black soldiers such as Edward Rollins, who in their struggles to create a better nation, gave their country the last full measure of devotion.

*The lives of Daniel Fossett and William Page are detailed in an essay by Matthew Wallace on the Battle of the Crater. Joseph H. Thomas, Nimrod Goins, and Isaiah Reed are all discussed in Wallace’s essay on the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm.

Matthew Weisenfluh pursued a double major in Financial Economics and Statistics with an Econometrics concentration, as well as a minor in History at UVA, graduating in May 2020. He worked for the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History for two years, contributing to both the "UVA Unionists" and the "Black Virginians in Blue" projects.

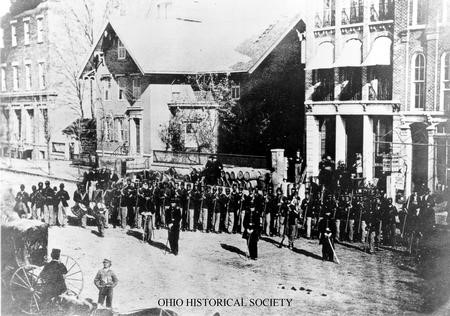

Images: (1) Interior view of the first three transverses at Fort Fisher (courtesy Library of Congress); (2) 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, also known as the 5th United States Colored Troops, in formation on Sandusky Street, Delaware, Ohio ca. 1863 (courtesy Ohio History Connection); (3) Bombardment of Fort Fisher by Porter’s fleet (courtesy Library of Congress); (4) Close-up of Edward Rollins’s pension application, detailing his wound suffered near Richmond (courtesy National Archives and Records Administration).

Sources: Compiled Service Records for Joseph H. Thomas, John M. Winfrey, William Page, John H. Hopkins, John Hailstock, Nelson Means, Thomas Walker, Thomas Gibson, Nimrod Goins, Lewis L. Winfrey, Edward Rollins, Isaiah Reed, Daniel Fossett, William Harris, William Spears, RG 94, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.; Pension Records for Joseph H. Thomas, John M. Winfrey, William Page, John H. Hopkins, John Hailstock, Nelson Means, Thomas Gibson, Nimrod Goins, Lewis L. Winfrey, Edward Rollins, Isaiah Reed, William Harris, William Spears , RG 15, NARA, Washington, D.C.; Frederick A. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 3 (Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company, 1908); United States Federal Census, 1860; United States Federal Census, 1870; David A. Gerber, Black Ohio and the Color Line 1860-1915 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1976); Ohio History Center, “African Americans”, https://ohiohistorycentral.org/index.php?title=African_Americans&mobileaction=toggle_view_desktop; David W. Kummer, Fort Fisher December 1864-January 1865 in U.S. Marines in Battle (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2012).