Nativism and Unionism: UVA’s Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart Before the Civil War

by Jesse George-Nichol | | Wednesday, July 18, 2018 - 10:40

Last year this blog highlighted the University of Virginia’s erasure of its Union army veterans in the aftermath of the Civil War. Brian Neumann’s posts about William Meade Fishback, James Overton Broadhead, and Joseph Cabell Breckinridge remind us that Virginians understood their obligations to their state, to the South, and to the Union differently, leading neighbors, friends, and classmates to choose different sides of the conflict. After the war, Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart—another UVA alum—described it this way: “Before the war every citizen owed allegiance to his State as well as to the United States. He was bound to defend both. It was thus a double or a divided allegiance with the line of demarcation not very distinctly defined. When, therefore, a conflict occurred it was not always easy to determine the path of duty or safe to pursue it, for what was obedience to one might be treason against the other.” For Stuart, as for so many others, the decision about what to do at the outbreak of civil war was terribly fraught. Unlike the “unconditional” Unionists who never accepted the Confederacy, Stuart ultimately acquiesced in Virginians’ decision to secede, but he counted himself among the most reluctant of Confederates.[1]

Stuart had spent many years fighting against sectional alienation and for the perpetuation of the Union. He played a prominent role in compromise efforts before the war, acting as one of the leaders of the Unionist faction at the Virginia Convention of 1861 (often called the Virginia Secession Convention). He was one of the delegates sent to meet with Lincoln in early April 1861, and when their work was interrupted by the outbreak of hostilities at Fort Sumter, he returned to the Virginia Convention to plead against secession. Even after Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion in the South, Stuart asserted that Border State Unionism—which he saw as the bulwark against Deep South secessionism and Northern abolitionism—could prevail. If Virginia stood between the administration and the seceded states, he told the convention on April 16, “instead of the bloody war which we now expect, we might have a peaceable adjustment of our difficulties.” The next day, the convention passed an ordinance of secession.[2]

Stuart’s efforts to hold the Union together long predated the secession crisis and the outbreak of war. During the mid-1850s those labors were deeply, if paradoxically, intertwined with nativism. Stuart and many other self-styled sectional moderates embraced the American or Know Nothing Party in hopes that it could rescue the Union from the political turmoil of the 1850s. Stuart’s tenure in the short-lived American Party highlighted important features of his commitment to the Union—beliefs that undergirded his attempts to pursue compromise and avoid secession and civil war. But the American Party’s failure also exacerbated differences between political moderates in the South and elsewhere, making Unionists’ task more difficult in 1860-1861.

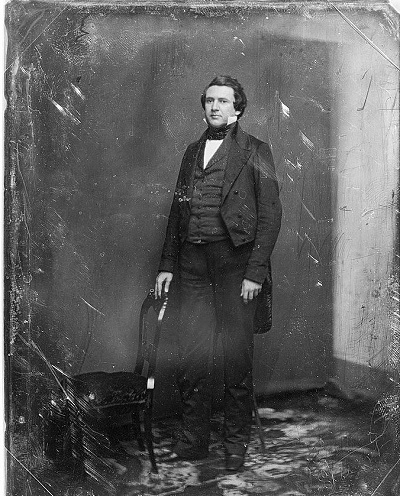

Alexander H. H. Stuart hailed from one of Virginia’s most prominent families. He cut an imposing figure at 6’4” tall with dark eyes, and thick, black hair. He attended the College of William and Mary and then studied law at the University of Virginia starting in 1827. After passing the bar the following year, he became a successful lawyer in his native Staunton. Stuart was drawn to politics, making his public debut stumping for Clay in the 1832 presidential election. He gained a reputation as a powerful speaker and a promising young Whig, entering the Virginia House of delegates in 1835, serving in the United States Congress for a single term from 1841-1843, joining Millard Fillmore’s Cabinet as Secretary of the Interior in 1850, and eventually returning to the state Senate in 1857. During his career, Stuart was known for his political moderation and zealous attachment to the Union.[3]

Though he had been a faithful Whig, Stuart was convinced by late 1853 that the old policy disputes that separated the Whig and Democratic parties had fallen away. Increasingly he saw more fundamental questions at issue: radicalism and sectionalism on one side and moderation and Unionism on the other. For the rest of the decade, he labored to create—as he put it in 1855—a “great constitutional union party,” which “could rally to its support all of the conservatives of the country” against Democratic corruption and demagogic fanaticism. He embraced the nativist American Party, hoping that it could be the locus of political moderation that he had been longing for. His investment in the party and its nativist doctrines was not merely instrumental to his goal of forming a Union party. Although only about two percent of Virginia’s population was foreign-born, Stuart had become convinced that “foreign influence” was at the root of the corruption and extremism that was plaguing American politics. “The vital principle of the American party is Americanism, developing itself in a deep-rooted attachment to our own country, its constitution, its union, and its laws; to American men and American measures, and American interests; or in other words, a fervent patriotism,” he explained in 1856. The party aimed to “arrest the tide of radicalism, and socialism, and black republicanism” that was menacing the Union by “recalling the people of all parts of the confederacy to a proper sense of their duty to the constitution, to each other, & to the country.”[4]

In explaining his commitment to the American Party, Stuart expressed something fundamental about the emotive Unionism of nineteenth-century Americans. For Stuart and his contemporaries, the Union was more than the confederation of states that composed it; it represented the republic—the American experiment in self-government that stood as a beacon of political liberty in a world that seemed to be trending in the other direction. This sense of American exceptionalism fueled Stuart’s suspicions about foreigners and their growing influence in American politics. The mid-nineteenth century witnessed a surge in immigration to the United States and an increasingly rancorous political controversy over slavery—and Stuart, along with other nativists, came to believe that these changes were linked. In their view, foreigners unschooled in “the principles of liberty, and the practical workings of free institutions” were ruled by their “pleasure” and “prejudices”; this had encouraged corruption and extremism among politicians who, in order to gain immigrants’ favor, “must sink to their level.” Stuart saw these tendencies at work in the Democratic Party—Democrats’ profligacy, corrupt electoral practices, and reckless agitation of the slavery issue were all closely tied, he reckoned, to their pursuit of immigrant votes. But immigrants bred in the monarchies and rampant revolutions of Europe brought “wild and demoralizing ideas” with them, too. These ideas, especially those aimed at extreme social change like abolitionism and women’s rights, were radicalizing and polarizing American politics—a trend epitomized by the Republican Party and its German stalwarts.[5]

Stuart thus believed that foreign influence was at the heart of the corrupt and divisive politics of the 1850s. This explanation for the country’s political woes was reassuring to Stuart in no small part because it reinforced his faith in Americans’ capacity—perhaps even their unique capacity—for self-government. It signaled that there was no fatal flaw in the American republic or widespread degeneration within the American populace; on the contrary, it reaffirmed Americans’ exceptional status by identifying the problem as external to the native body politic. In short, this explanation enabled Stuart to reconcile the degradation of American politics with his Unionism. It allowed him to believe that the virtuous patriotism that had sustained the republic still lived in the hearts of most native-born Americans, and that it might still prevail over the extremism of “outsiders” and of the demagogues who, as he saw it, catered to them.[6]

This conviction fed Stuart’s pursuit of sectional compromise during the tumultuous 1850s. Still, the nativist Unionism he extolled while campaigning for the American Party in 1856 failed to garner the kind of support that he had hoped. Millard Fillmore, the party’s presidential candidate, received a paltry eight electoral votes, losing to Democrat James Buchanan in Virginia by a twenty-point margin. The American Party’s demise in the aftermath of the 1856 election, as Northerners flocked to the Republican banner, dashed Stuart’s hopes that it could be a nucleus of political compromise. Thereafter he toned down his nativist rhetoric, though the persistence of nativism in the South—in Confederate characterizations of Union armies as “mongrel” hordes made up “largely of felons, foreigners, and Negroes,” for example— attested to the issue’s continued relevance to Southerners. During the secession crisis of 1859-61, both in the Constitutional Union Party and at the Virginia Convention of 1861, Stuart took a different tack, focusing on harmonizing sectional interests through economic development and interdependence. But the abortive American Party had exposed divisions among political moderates in Virginia and across the country. These differences would make Stuart’s project harder, as thorny political loyalties and deep-seated prejudices complicated his attempts to unite Unionists against the growing threats of sectionalism, secession, and civil war.[7]

Jesse George-Nichol is a PhD candidate in the Corcoran Department of History at UVA. Her research focuses on former Whigs in the Upper South and the Border South and their attempts secure a national adjustment and avoid armed conflict.

Image: Alexander H. H. Stuart (courtesy Library of Congress).

Notes:

1. Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Address to the Mass Meeting of the People of Augusta, May 8, 1865” in Alexander H. H. Stuart, A Narrative of the Leading Incidents of the Organization of the First Popular Movement in Virginia in 1865 to Re-Establish Peaceful Relations Between the Northern and Southern States, and of the Subsequent Efforts of the ‘Committee of Nine,’ in 1869, to Secure the Restoration of Virginia to the Union (Richmond, Va.: Wm. Ellis Jones, 1888), 9.

2. “Speech of Mr. A. H. H. Stuart, of Augusta, April 16, 1861” in Proceedings of the Virginia State Convention of 1861: February 13-May 1, ed. George H. Reese (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1965), IV: 9-21, quotation p. 18; Alexander F. Robertson, Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart, 1807-1891: A Biography (Richmond: The William Byrd Press, Inc., 1925), 181-203.

3. Robertson, Stuart, 11-163.

4. Alexander H. H. Stuart to Nathan Sargent, October 27, 1855, Nathan Sargent Papers, Grand Valley State University Special Collections and University Archives, Allendale, Michigan; Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Madison Letter Number One (originally published in the Richmond Whig),” in Robertson, Stuart, 64; Alexander H. H. Stuart to William Gannaway Brownlow, August 18, 1856, Papers of Archibald Stuart and Briscoe Gerard Baldwin, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia [collection hereafter cited as Stuart and Baldwin Papers, UVA]; Alexander H. H. Stuart to Millard Fillmore, December 6, 1853, January 3, 1854, Millard Fillmore Papers, Special Collections, State University of New York at Oswego, Oswego, New York; Robertson, Stuart, 56-162; “Nativity of the Population, for Regions, Divisions, and States: 1850 to 1990,” U.S. Bureau of the Census, released March 9, 1999, https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0029/tab13.html.

5. Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Madison Letter Number Eight (originally published in the Richmond Whig),” in Robertson, Stuart, 115-22, quotations pp. 115, 119, 120-21; Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Madison Letter Number Seven (originally published in the Richmond Whig),” in Ibid, 109-14; Alexander H. H. Stuart to William Gannaway Brownlow, Stuart and Baldwin Papers, UVA; Elizabeth Varon, Disunion!: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 4-5; Matthew Mason, A Political Biography of Edward Everett (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 2-3; Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 3-19.

6. Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Madison Letter Number Eight (originally published in the Richmond Whig),” in Robertson, Stuart, 115; Alexander H. H. Stuart, “Madison Letter Number Two (originally published in the Richmond Whig),” in Ibid, 73-80.

7. George Rable, Damn Yankees!: Demonization and Defiance in the Confederate South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2015), 31-48, quotations pp. 38, 39; Alexander H. H. Stuart to Henry C. Carey, et al., January 12, 1860, Staunton Spectator (Staunton, VA), February 14, 1860; Robertson, Stuart, 163-204; Donald R. Deskins, Jr., Hanes Walton, Jr., and Sherman C. Puckett, Presidential Elections, 1989-2008: County, State, and National Mapping of Election Data (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010), 155-166; John Burgess Stabler, “A History of the Constitutional Union Party: A Tragic Failure” (dissertation, Columbia University, 1954).