Shenandoah at War (Part 1): Overview

by Gary W. Gallagher | | Tuesday, February 28, 2017 - 14:28

The Nau Center’s Signature Conference for 2017 will focus on the Shenandoah Valley’s role in the Civil War. Lecturers will examine various facets of the overall topic, including military operations, civilian experiences, how events in the Valley resonated in the United States and the Confederacy, and how the Valley figured in memories of the conflict. In this, the first of three installments anticipating the conference, I will examine the Valley's geography and logistical and strategic significance.

The Shenandoah Valley cuts a fertile, rolling slash between Virginia's piedmont and the rugged mountains of the state's antebellum western regions. A landscape of breathtaking beauty and agricultural bounty, it extends from the Potomac River to beyond Lexington in Rockbridge County. With the Blue Ridge Mountains on the east and the more imposing Alleghenies to the west, the Valley runs southwest to northeast and drops gently in its course to meet the Potomac. The forks of the Shenandoah River thus flow south to north (or southwest to northeast), which means that an individual traveling toward the Potomac goes "down the Valley"—an odd circumstance in a world where north is almost always "up." Between Strasburg and Harrisonburg, Massanutten Mountain divides the Valley. West of Massanutten, in the Valley proper, the North Fork of the Shenandoah River meanders toward the Potomac, while to the east the South Fork runs through the Luray (or Page) Valley on its journey to join the North Fork at Front Royal. The lower Valley, as the northern portion is known, includes the broad expanse between Williamsport on the Potomac and Strasburg, as well as the land west of Massanutten Mountain as far south as Woodstock. A secondary valley parallels the northeastern flank of the Shenandoah, nestling between the Blue Ridge and the modest bulk of the Bull Run Mountains.

The logistical value of the Valley during the war scarcely can be overstated. The region’s agricultural riches promised sustenance for Confederate forces in Virginia. The most important wheat growing area of the entire Upper South through most of the antebellum period, it also led Virginia in production of other grains and cattle and contributed substantial quantities of leather, wood products, woolen textiles, and whisky. No rail system served the entire Valley, but three lines provided links to northern and eastern Virginia. The Virginia Central crossed the Blue Ridge near Waynesboro and ran to Staunton, the largest rail depot in the Valley, and thence to Covington; the Manassas Gap Railroad connected Mount Jackson, Strasburg, and Front Royal to Manassas Junction via Thoroughfare Gap in the Bull Run Mountains; and the Winchester and Potomac Railroad, a spur of the mighty Baltimore and Ohio (B&O), penetrated the lower Valley from Harpers Ferry to Winchester. Supplementing these railroads as an artery for the movement of logistical goods and armies was the macadamized Valley Turnpike, which provided all-weather service between Staunton and Martinsburg.

The Valley loomed large as a strategic avenue whence either side could mount a threat to the western flanks of Washington and Richmond. All of the Valley below Strasburg lay north of the United States capital. A Confederate army marching down the Valley, screened by cavalry in the gaps of the Blue Ridge, might easily cross the Potomac and descend on the right rear of Washington. The B&O was vulnerable to Confederate attack where it dipped south of the Potomac between Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. Moreover, any Federal advance through north-central Virginia along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad would present an open right flank to Confederates positioned behind the passes in the Blue Ridge. Similarly, Federals moving up the Valley could cut the rail lines to eastern Virginia, thereby disrupting the flow of supplies to the soldiers defending Richmond, while at the same time placing in jeopardy the left flank of any Confederate army between the Occoquan and the Rappahannock-Rapidan River line.

The Valley loomed large as a strategic avenue whence either side could mount a threat to the western flanks of Washington and Richmond. All of the Valley below Strasburg lay north of the United States capital. A Confederate army marching down the Valley, screened by cavalry in the gaps of the Blue Ridge, might easily cross the Potomac and descend on the right rear of Washington. The B&O was vulnerable to Confederate attack where it dipped south of the Potomac between Harpers Ferry and Martinsburg. Moreover, any Federal advance through north-central Virginia along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad would present an open right flank to Confederates positioned behind the passes in the Blue Ridge. Similarly, Federals moving up the Valley could cut the rail lines to eastern Virginia, thereby disrupting the flow of supplies to the soldiers defending Richmond, while at the same time placing in jeopardy the left flank of any Confederate army between the Occoquan and the Rappahannock-Rapidan River line.

The Valley invited attention from planners in Washington and Richmond throughout the war. For example, Ulysses S. Grant addressed the military and economic importance of the Valley in early August 1864, instructing General David Hunter to pursue rebels under General Jubal A. Early relentlessly. With an eye toward logistics (but indifferent attention to capitalization and punctuation), Grant instructed Hunter that in moving “up the Shenandoah Valley . . . it is desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return. Take all provisions, forage and Stock wanted for the use of your Command. Such as cannot, be consumed destroy.” How major operations played out in the Valley will be the focus of the next installment of this overview.

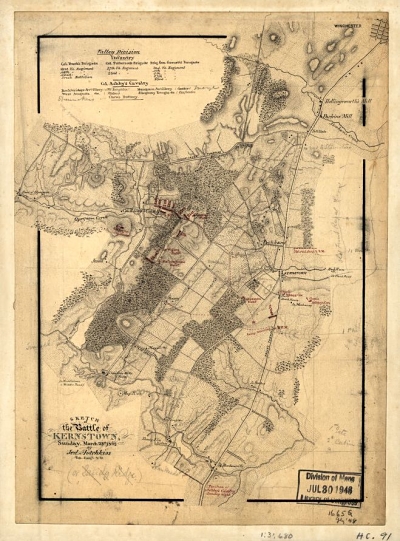

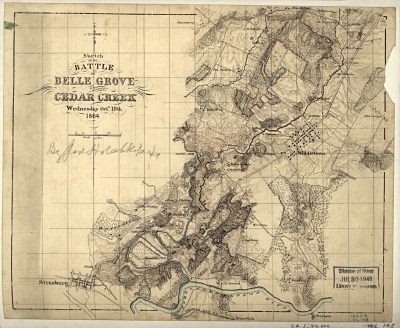

Images: Battlefield maps of Kernstown (1862) and Cedar Creek (1864) by famed Confederate cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss (Library of Congress).