Seeking a “Durable Peace”: The Story of UVA Republican Thomas M. Mathews

by Brian Neumann | | Friday, April 23, 2021 - 10:04

The vast majority of UVA alumni opposed Reconstruction and worked to dismantle its achievements. As political and cultural leaders, they played a major role in reasserting white supremacy and constructing the southern “Lost Cause” memory of the war. Even most UVA Unionists were political conservatives who fiercely defended the South’s racial hierarchy. Once the war was over, Unionists like William M. Fishback and James O. Broadhead called for reconciliation with former Confederates and demanded strict Black Codes to limit African American freedom. A few UVA alumni, however, embraced the Republican Party and accepted the dramatic transformations of the postwar world. During Reconstruction, southerners like Thomas M. Mathews allied with former slaves and northern Republicans to rebuild the Union and ensure a just and “durable peace.”[1]

Before the war, Mathews had been a prominent planter and local Democratic Party leader. As a proslavery Unionist, he believed that the Constitution sanctioned and safeguarded the South’s “peculiar institution.” The secession crisis placed tremendous strain on his loyalties, and he publicly endorsed disunion. During the war, he largely retreated from public life, and he later insisted that he had remained secretly faithful to the Union. After Confederate defeat, he joined the Republican Party, defended Reconstruction, and upheld African American suffrage and civil rights. His story reveals the complicated nature of wartime loyalty and sheds light on the ideals, anxieties, and motivations of southern Republicans.

Thomas Meriwether Mathews was born in Georgia around 1814 to Charles Lewis Mathews and Lucy Early. In the late 1810s, the family moved to the newly-organized Alabama Territory, where Charles helped establish the town of Selma. Thomas enrolled at the University of Alabama in the early 1830s, but administrators suspended him in February 1833 for “insurbordination [sic] and contempt of lawful authority.” He then transferred to the University of Virginia, where he spent two years studying natural philosophy, mathematics, and ancient languages. He was an indifferent student who often drank, partied, overslept, and failed to pay his bills. In November 1833, he was suspended for two weeks for getting drunk and using “indecent expressions” at a party, and in March 1835, he left grounds without permission to serve as a second in a classmate’s duel. He withdrew from UVA later that year and returned to Dallas County, Alabama. His father, “the richest man, perhaps, in Alabama,” died in June 1843, and Mathews inherited a large portion of his plantation. By 1860, he owned at least 143 slaves and more than 4,000 acres of land, together worth nearly $500,000.[2]

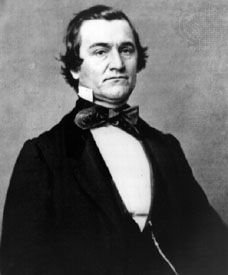

Mathews became a civic and political leader in his county. He served as a local Democratic Party delegate, attended railroad and commercial conventions, and spearheaded local reform and disaster relief efforts. In the late 1840s, Alabama’s Democratic Party began splintering. Radicals like William Lowndes Yancey demanded federal protections for slavery and threatened to tear the party—and, perhaps, the Union—apart. Mathews and his allies, however, championed moderation, insisting that only a unified Democratic Party could hold the country together. In April 1860, Yancey persuaded dozens of Deep South delegates to walk out of the National Democratic Convention after it rejected a militant pro-slavery platform. Democrats scheduled a new party convention in Baltimore that June, and Alabama’s fracturing party elected two slates of delegates. Radicals reelected the original delegates (including Yancey), while moderates selected Mathews and other men committed to repairing the Democratic Party. The Baltimore convention seated Mathews’s delegation and nominated Stephen A. Douglas for president. Radicals, in turn, organized their own convention and selected Kentucky statesman John C. Breckinridge.[3]

In the election of 1860, Breckinridge carried Alabama by a decisive margin, but Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln ultimately triumphed. In response, Governor Andrew B. Moore scheduled elections for a secession convention. Mathews ran for a seat as a cooperationist, warning that “Separate State Secession” would lead to “inevitable ruin and destruction.” He sadly declared the “present Union…ended,” and he urged southerners to “form another and new Union among ourselves.” While radicals hoped to secede immediately, Mathews counseled patience and called for “consultation with all the slave States.” If the southern states seceded together, he claimed, they could “form a government sufficiently powerful to insure peace at home, command respect abroad, repel aggressions and redress wrongs.” Most Dallas County voters, however, considered Mathews too moderate, and an “immediate secessionist” won the election by a vote of 1,015 to 358.[4]

Although most Alabamians embraced the Confederacy, several thousand remained loyal to the Union. Roughly 3,000 White residents served in the Union army, and countless others fled the state rather than betray their convictions. As one scholar explains, however, most Unionists and disaffected Confederates remained at home and “lapsed into effective neutrality.” Mathews conformed to this pattern. He retreated from civic life and made few, if any, public statements during the war. His neighbors decried his lukewarm loyalty and repeatedly threatened his life. According to one witness, a local Confederate threatened to “fill him full of buck shot as he [came] through to Selma.” In response, Mathews purchased $5,000 in Confederate bonds and agreed to sell cotton and fodder to the Confederate government. After the war, he claimed he had done this “under pressure, with no intention to aid the Confederacy, but [rather] as protection.”[5]

Although federal armies made few major incursions into southern Alabama, Mathews found small but important ways to serve the Union cause. He sent food to the Union soldiers at a nearby prison camp and helped several prisoners escape by hiding them in his gin house. His neighbors “regarded him as a union man,” and friends later testified that his private conversations were all “in favor of the union.” On April 8, 1865, Union General James Wilson and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest met at Mathews’s house to arrange Forrest’s surrender. Wilson declared Mathews a “gentleman of great intelligence and high character” who had “never given up his allegiance to the Union.”[6]

Throughout the war, local African Americans seized every opportunity to flee from bondage. In early 1862, one resident reported, Confederate soldiers patrolled Dallas County to “watch the Yankees, and keep the negroes from running off.” County newspapers published dozens of fugitive slave notices, revealing African Americans’ determination (in one planter’s words) to “join the Yankees, wherever [they] can.” The arrival of Union forces in April 1865 brought freedom to those who remained. As Union ships steamed up the Alabama River, one writer recalled, the “banks were lined with negroes from the neighboring plantations,” and these African Americans “all left” their former owners. Few sources document the impact of the war on Mathews’s slaves. In the early 1870s, freedmen Jim Jordan and Joseph Murray testified that they “used to belong to him, and have worked for him ever since the surrender, except one year.” They confirmed Mathews’s Unionist convictions and noted that he “kept them posted” about wartime events, but they said nothing about their own hopes and anxieties during the war.[7]

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson offered “general amnesty” to all but the highest-ranking and wealthiest Confederates. He required planters to request formal pardons and accept the “enormity of their crime,” and Mathews complied in July 1865. He assured the president that he had remained “devoted to the Union” throughout the war. Any “semblance of recognition of the so called Confederate authority” he insisted, stemmed only from “force of circumstances.” The president promptly pardoned him, and Mathews served in Alabama’s constitutional convention later that year. There, he helped disavow secession, repudiate the state’s Confederate war debt, and affirm the death of slavery.[8]

In Alabama, and across the South, most Confederates remained impenitent. Voters defiantly restored Confederate statesmen to power and approved repressive Black Codes to limit African American freedom and mobility. As Huntsville Unionist Joseph Bradley observed, “our State has gone wild.” Most of Alabama’s new state legislators had served in the Confederate army, and every “Member of Congress elected Cannot take the oath of office.” In response, Republicans in Congress seized control of Reconstruction. They disenfranchised former Confederates, refused to seat most southern congressmen, and extended civil rights and suffrage to African Americans.[9]

Mathews carefully navigated these shifting political tides. He ran for a seat in Congress in the fall of 1865, vowing to “advance the interest of my State and people” and “restore them to their rights.” He emphasized his “conservative views” and reminded voters that his sons had “shared the trials and hardships” of Confederate service. He was overwhelmingly defeated by Charles C. Langdon, an ardent and unrepentant Confederate, and Mathews then aligned himself with the state’s emerging Union Party. In November 1866, a convention of “truly loyal men of Alabama” asked Mathews to travel to Washington, D.C., to “consult with the republican members of Congress” and determine the “most efficient means of reclaiming the state of Alabama from rebel rule.” Union General John McArthur assured congressmen that Mathews was “one of the few uncontaminated by rebellion and deeply interested in the work of reconstruction.”[10]

In March 1867, Mathews helped organize a “Union Republican Convention” in Huntsville. The delegates championed Congressional Reconstruction and urged White Unionists and freedmen to band together to rebuild their state. The “spirit of Republican Government,” they resolved, “requires the equality in law of the citizens.” They called for Black suffrage and civil rights and declared a “strong Central Government…indispensable to the liberties of the people.” Although they hoped to reconstruct Alabama “as speedily as possible,” they denounced political violence and vowed to “preserve peace, order, and decorum.”[11]

That June, Mathews represented Dallas County in the Union Republican State Convention. Delegates defended Black political and legal equality, championed free education, and urged legislators to repeal Alabama’s poll tax. As one scholar observes, they carefully appealed to both freedmen and White moderates, hoping to “perform a miracle and weld these two blocs into a firm foundation for the Republican party.” In the short-term, at least, their strategy appeared successful. Thousands of former Confederates remained disenfranchised, and many more boycotted the polls out of disgust and alienation. As a result, by September 1867, nearly 55 percent of the state’s registered voters were Black. Mathews served on the local voter registration board, helping enroll White and Black men loyal to the federal government. Over the next year, these Alabamians drafted a more egalitarian state constitution, ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, and elected the state’s first Republican governor. When Congress readmitted Alabama’s representatives the following year, both senators and all six congressmen were Republican.[12]

Mathews supported Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant in the election of 1868. Grant, he observed, was “no politician; but is a ‘people’s man,’ and his every action will tend to the good of his country.” Above all, Grant desired a “durable peace,” and he would protect wartime Unionists and former slaves while “build[ing] up our poverty-stricken and demagogue-ridden people.” Mathews argued that the “remedies which would have served to save [the Union] in 1865 will not now meet the emergency.” Former Confederates, he explained, sought to unravel Reconstruction, terrorize Republicans, and regain control of the South. They had driven the “country into secession and ruin [and] established a reign of terror,” and now they hoped only to provoke further chaos and bloodshed. A Democratic victory, he warned, would help return these men to power and signal the “triumph of Secession.”[13]

Southern Democrats declared the United States a “white man’s government” and accused Republicans of fighting for “negro supremacy.” Mathews, however, dismissed this as “clap trap.” The Republican Party, he argued, was a “party of principles,” and it welcomed all men regardless of race or previous condition. Republicans “simply propose to give the negro a fair chance to improve his condition, and to elevate himself and his race.” While Democrats sought to divide and destroy, he said, Republicans hoped to reunite the country and restore justice, peace, and prosperity. Mathews called upon voters to “repudiate [Democrats] as leaders, reject them as advisors, and take their fate into their own hands.”[14]

As president, Grant reportedly planned to appoint Mathews as customs collector for Mobile, Alabama. General Wilson assured Grant that Mathews was “one of the very best friends of the Union” and a staunch supporter of Reconstruction. Grant changed course, however, after the state’s senators backed Unionist planter William Miller, a moderate Republican whom they claimed would satisfy “all men of all parties in Alabama.” Supporters floated Mathews’s name as a gubernatorial candidate in the 1870 and 1872 elections, but he never received the Republican Party’s nomination. Mathews’ health began to decline in the early 1870s. In 1872, he suffered a “violent attack” of malaria and briefly fell into a coma. After he recovered, the family moved to Pensacola, Florida, and Mathews died there on September 17, 1874.[15]

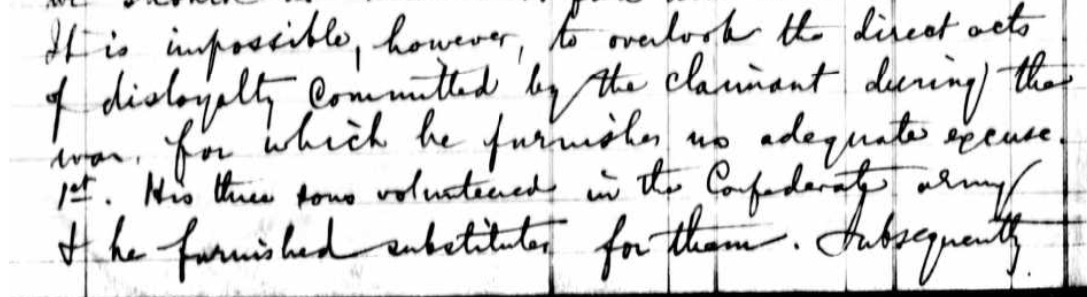

In the final years of his life, Mathews faced lingering questions about the nature of his wartime loyalty. In 1871, he had requested $5,000 from the Southern Claims Commission, which compensated loyal southerners for supplies taken by the Union army during the war. The commissioners, however, rejected his request, insisting that he had committed “direct acts of disloyalty.” By purchasing war bonds and selling cotton, he had “sustain[ed] the credit of the Confederacy” and given aid and comfort to the Union’s enemies. By applying for a pardon, Mathews had proven his guilt, because pardons were “only necessary” for those who had taken part in the Confederate rebellion. Mathews, they concluded, had “fixed his own status by that act.” Nonetheless, the commissions recognized Mathews’s Unionist convictions, conceding that he “desired the success of the federal cause.” He remained secretly faithful to the federal government, and after the war, he “supported the reconstruction measures of Congress” and helped “restore the state to the Union.”[16]

As historian Michael Fitzgerald observes, few Alabamians could “meet a legal standard of consistent loyalty.” Despite Mathews’s claims, his words and actions suggest that he had not remained unconditionally loyal to the federal government. During the secession winter, he had declared the “present Union…ended” and called for a new Southern Confederacy. By purchasing war bonds and selling supplies to the army, he confirmed his complicity in the Confederate cause. Even so, as Fitzgerald writes, “the Union name meant something real, though imprecise.” Mathews offered food and shelter to Union soldiers and faced death threats from his Confederate neighbors. He considered himself a Unionist, and that conviction helped guide him through the crises of Reconstruction. After the war, unbowed Confederates violently struggled to “redeem” the South from Republican rule. In response, Mathews and thousands of other southern Republicans allied with former slaves and northern migrants to rebuild the Union and contest the future of their states.[17]

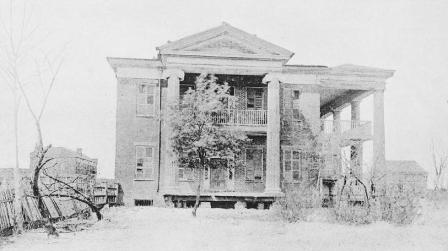

Images: (1) Home of Thomas M. Mathews (courtesy Geneaologytrails.com); (2) William Lowndes Yancey (courtesy Wikicommons); (3) Rejection of Mathews's filing with the Southern Claims Commission (courtesy National Archives and Records Administration).

[1] Thomas M. Mathews, “To the People of Alabama,” 13 October 1868, Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com; James Alex Baggett, The Scalawags: Southern Dissenters in the Civil War and Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003); Elizabeth R. Varon, “UVA and the History of Race: The Lost Cause Through Judge Duke’s Eyes,” 4 September 2019, UVA Today; Kate Schneider, “Civil War Memory at UVA,” available from http://www.kas6wa.wixsite.com/civilwarmemoryuva.

[2] Alston Fittz III, Selma: A Bicentennial History Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016), 49; James Benson Sellers, History of the University of Alabama, Vol. 1: 1818-1902 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1953), 204; Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Session of 1833-34 (Charlottesville, VA: Watson & Tompkins, 1834); Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Session of 1834-35 (Charlottesville, VA: Moseley & Tompkins, 1835); Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty for Session 10, 1833-1834; Journals of the Chairman of the Faculty for Session 11, 1834-1834; Proctor’s Monthly Report for May 1834 available from http://www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; Cahawba Democrat, 20 October 1838; 1860 United States Federal Census, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[3] James H. Wilson to Ulysses S. Grant, 2 March 1869, US Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com; The Cahaba Gazette, 16 November 1855, 8 August 1856, 5 June 1857; The Clarke County Democrat, 5 May 1859; Lonnie A. Burnett, “Precipitating a Revolution: Alabama’s Democracy in the Election of 1860,” The Yellowhammer War: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama, ed. Kenneth W. Noe (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2013), 18-24.

[4] The Cahaba Gazette, 13 July 1860; The Alabama State Sentinel, 14 November 1860; Fitts, Selma, 49.

[5] Clayton Butler, “True Blue: White Unionists in the Deep South during the Civil War and Reconstruction, 1860-1880” (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 2020); William Kauffman Scarborough, Masters of the Big House: Elite Slaveholders of the Mid-Nineteenth-Century South (Baton Rouge; Louisiana State University Press, 2003), 331; Michael W. Fitzgerald, Reconstruction in Alabama: From Civil War to Redemption in the Cotton South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 22; Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[6] Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com; James Harrison Wilson, Under the Old Flag: Recollections of Military Operations in the War for the Union, Vol. II (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1912), 241.

[7] The Daily Selma Reporter, 30 May 1862; Catherine McRae to James McRae, 24 February 1862, Colin J. McRae Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History; Mary Ann Hall to Sister, 4 July 1865, Alexander K. Hall Family Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History; Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[8] Confederate Applications for Presidential Pardons, 1865-1867, available from http://www.ancestry.com; Joshua Shiver, “Reconstruction Constitutions,” Encyclopedia of Alabama, available from http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-4192.

[9] Joseph C. Bradley to Andrew Johnson, 15 November 1865, The Papers of Andrew Johnson, Vol. 9: September 1865-January 1866, ed. Paul H. Bergeron (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1991).

[10] The Montgomery Advertiser, 17 October 1865; Christopher Lyle McIlwain, Sr., 1865 Alabama: From Civil War to Uncivil Peace (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2017), 192; Ben H. Severance, A War State All Over: Alabama Politics and the Confederate Cause (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 2020), 60.

[11] The Selma Times and Messenger, 3 April 1867.

[12] Selma Weekly Messenger, 27 April 1867; Fitts, Selma, 104; Union Springs Herald, 29 May 1867; Sarah Woolfolk Wiggins, The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1977), 22; Michael W. Fitzgerald, Reconstruction in Alabama: From Civil War to Redemption in the Cotton South (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017), 149.

[13] Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[14] Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[15] The Montgomery Advertiser, 19 March 1869; The Selma Times, 20 March 1869; Michael W. Fitzgerald, “Republican Factionalism and Black Empowerment: The Spencer-Warner Controversy and Alabama Reconstruction, 1868-1880,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 64, No. 3 (August 1998), 474-494; The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 21: November 1, 1870-May 31, 1871, ed John Y. Simon (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1998), 21n; The Times Argus, 8 November 1872; The Montgomery Advertiser, 24 September 1874; The Tuskaloosa Gazette, 1 October 1874.

[16] Susanna Michele Lee, Claiming the Union: Citizenship in the Post-Civil War South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014); Southern Claims Commission Disallowed and Barred Claims, available from http://www.ancestry.com.

[17] Fitzgerald, Reconstruction in Alabama, 56.