“Equal Justice South and North”: Benjamin F. Dowell and the Radicalization of War

by Brian Neumann | | Friday, April 16, 2021 - 16:03

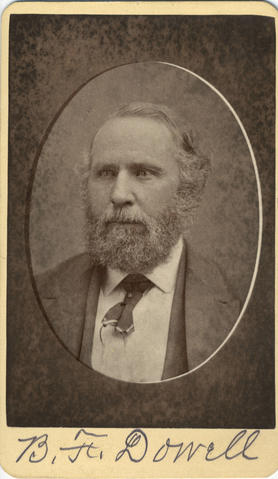

Like most nineteenth-century Americans, UVA’s Unionists were mainly political moderates who hoped to restore rather than radically alter the Union. Many, for example, supported emancipation as a military necessity but hoped to keep southern society essentially unchanged. For a few alumni, however, the war and its aftermath were radicalizing experiences that forced them to cast off old convictions. For men like Benjamin F. Dowell, the only way to permanently preserve the Union was to punish Confederate leaders, empower African Americans, and dramatically reconstruct the southern states. Dowell was a slaveholder’s son who became a champion of freedom—a moderate Whig who embraced Radical Reconstruction and the “eternal principles of equal rights…without regards to race, color, or sex.” His story speaks to the Civil War’s unforeseen, contested consequences and helps explain how a country of political moderates uprooted slavery and ratified the radical Reconstruction amendments.[1]

Benjamin Franklin Dowell was probably born on October 31, 1821, in Albemarle County, Virginia, to James Isham Dowell and Frances Dalton. His father, a descendant of Benjamin Franklin, worked as a farmer and owned at least 7 slaves. The family moved to Shelby County, Tennessee, in the 1830s, and his father died there in early 1840. His mother, a “woman of rare culture and refinement,” passed away three years later in August 1843. Dowell attended a male academy in Shelby County before enrolling at the University of Virginia to study law in 1841. He graduated with distinction the following year and spent the rest of the decade building a “lucrative and extensive” legal practice in Memphis, Tennessee.[2]

The California Gold Rush inspired Dowell to leave home and “try his fortune in the mines.” He joined a small wagon party in Missouri in May 1850 and arrived in San Francisco four months later. A cholera outbreak, however, nearly claimed his life, and doctors advised him to travel north to restore his health. He booked passage on a small schooner bound for the Oregon Territory, reaching Astoria in late November after a perilous seven-week voyage. With little legal work available, he accepted a teaching position near Salem. Then, in 1852, he purchased several mules and became a trader, carrying goods from the fertile Willamette Valley to the mining centers of southern Oregon.[3]

Violence erupted in 1853, as Native Americans in the Rogue River Valley forcefully defended their lands. The territorial governor called out the militia, and Dowell immediately “hired himself and all his animals to the quartermaster.” Over the next few years, he delivered messages and supplies to the soldiers and occasionally joined them on campaign. In December 1855, he took part in the Battle of Walla Walla, reportedly strapping a howitzer to the back of one of his mules. Dowell viewed the war as a struggle between “civilization” and “savage barbarity” and declared White settlers superior to “Negroes and Indians.” Even so, he strongly opposed the “extermination of the red race,” hoping instead to “Christianize and civilize the Indians.” After serving in the Rogue River War and the Yakima War, he returned to civilian life in early 1856. He became a lawyer and claims agent in Jacksonville, Oregon, helping settlers secure payment for their service in the Indian Wars.[4]

Dowell embraced the Whig Party’s platform of economic development and political moderation. As a teenager, he witnessed the party’s exuberant “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” presidential campaign, and the image struck a powerful chord. Decades later, he still celebrated the “political canvass of 1840, which…placed the hero General [William H.] Harrison in the White House.” In Oregon, although Democrats dominated the territorial government, Dowell remained loyal to the Whig Party “as long as it was in existence.” As late as 1855, he voted and delivered speeches for the Whigs’ congressional candidate. The party collapsed soon after, and, for the next few years, Dowell struggled to find a political home. In 1857, for example, he planned to vote without regard to “old party issues and old party names.” Crucially, however, he denounced “Black Republicanism, alias Negro-ism, in all its shapes and forms.” In the 1860 presidential election, he supported Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, whose running mate was Oregon Senator Joseph Lane.[5]

After the war, Dowell deeply regretted this vote and sought to cast it in a patriotic light. An early biographer, writing while Dowell was still alive, insisted he had cast his ballot “conscientiously, with the hope to keep peace between the North and South.” As a native Virginian, however, Dowell also retained deep ties to his native region. Many relatives still lived in the South, and he had formed lasting friendships with his southern classmates at UVA. He had grown up in a slaveholding household, and several brothers still owned slaves. In August 1861, Dowell defended Joseph Lane, whose support for slavery and secession had ended his political career. If the country’s leaders possessed even one-tenth of Lane’s “patriotism & practical sense,” Dowell declared, “our unhappy country would not now lay prostrate, bleeding at every pore.” At least three of Dowell’s brothers served in the Confederate army, and he expressed great anxiety for their safety.[6]

Early in the war, like many loyal Americans, Dowell remained politically moderate. In April 1862, he insisted that the “fanatical abolition party at the North and the secession nullification party at the South are both to blame for the present war.” He hoped that a “spirit of conciliation and compromise may prevail,” suggesting that Confederates would lay down their arms if northern states repealed their personal liberty laws. Nonetheless, he remained fiercely loyal to the Union. He had resisted “nullification, abolition, secession and disunion from a boy to the present time,” and he vowed to “live in the Union and under…the stars and stripes, as long as life shall last.” Although he “opposed many of the acts of the President [Abraham Lincoln]… yet I am for my government.” He prayed the Union cause would prevail and that “our star spangled banner may soon wave triumphantly and peacefully throughout every county in every State.”[7]

As historian Gary W. Gallagher explains, most loyal Americans were political moderates who went to war not to abolish slavery or transform the South but rather to preserve the Union. By 1863 or 1864, as it became clear that slavery helped sustain the Confederate war effort, many Americans accepted emancipation as a military necessity. After Confederate armies surrendered, however, they considered the “work of the war fully accomplished” and looked forward to a rapid process of political reunion. Only when White southerners emerged unbowed and unrepentant did many northerners embrace Reconstruction. The 14th Amendment, revealingly, contains one clause granting citizenship to African Americans and three clauses punishing former Confederates. For many Americans, the Reconstruction amendments were a radical means to a conservative end—a way to forestall future bloodshed and ensure the Union’s survival. Dowell’s story provides a dramatic example of this process, as he espoused not only the necessity but also the justice of Reconstruction.[8]

The Civil War steadily radicalized Dowell as he realized that “conciliation and compromise” could not restore the Union. In July 1864, he purchased the Oregon Sentinel newspaper, hoping to champion the Union cause and launch a political career. The Sentinel accused anti-war Democrats of treason, championed emancipation, and called for the “complete suppression of the rebellion.” Dowell spoke at several Unionist rallies that fall, including a “Grand Union Jubilee” in November 1864. There, he celebrated Abraham Lincoln’s reelection as the “ultimate triumph of Liberty, Freedom and Union.” For four years, the war had “deluged our once peaceful and happy country in fraternal blood,” and Dowell still could “only conjecture when or how it will end.” With Lincoln’s reelection, however, the American people had vindicated the Republican war effort and declared that the “Union must and shall be preserved.”[9]

Dowell denounced the “sins of treason and slavery” and declared the Emancipation Proclamation a “military necessity.” Slavery, he observed, had provoked the war and helped sustain the Confederacy, and the Union would never be secure as long as the “peculiar institution” survived. Unionists in West Virginia, Maryland, Louisiana, and Missouri had already set freedom in motion, and he prayed the rest of the South would follow their example. He hoped they would “join the great loyal North” and “strike for freedom—for our democratic, republican principles.” With slavery gone, he insisted, all Americans would have “equal rights, regardless of color, to acquire and hold property and to pursue their own happiness in their own way.” The “curse of slavery…the cause of the war, shall be wiped out, [and] Liberty, Freedom and true religion shall live and flourish forever on the American continent.”[10]

Dowell remained active in Unionist politics after the war. He delivered a eulogy for Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 and served as a delegate to the state’s Union Convention the following year. He initially trusted Andrew Johnson to punish Confederate “traitors” and protect freedmen and White Unionists. Instead, Johnson allowed Confederates to regain power across the South, and by 1867, Dowell began calling for the president’s impeachment. He fervently supported Ulysses S. Grant in the election of 1868, urging voters to “form Grant Clubs all over the State.” Dowell cast the election in apocalyptic terms, insisting that Republicans “are for peace, the Democrats are for war.” Democrats, he warned, had “marched under the war banner of the South for the last eight years.” If elected, they would “drive these [southern] States from the Union, and place them again under the control of secessionists and traitors.” Republicans, by contrast, would restore the Union “on a peaceful and loyal basis.” With Grant as president, he predicted, Reconstruction would become a “fixed fact,” and “union will rule and reign throughout the United States.”[11]

In 1867, while visiting his former homes in Tennessee and Virginia, Dowell witnessed White southern intransigence firsthand. The “Calhoun, rebel Democrats,” he reported, had turned Memphis into a “bubbling, seething cauldron.” In a racial riot the previous year, White mobs had murdered dozens of African Americans and set fire to Black houses, schools, and churches. Violence, Dowell discovered, was still simmering, as White residents terrorized former slaves with impunity. He learned that Confederates leaders were already re-writing the past, telling their followers that “the South has done no wrong, and that the greatest and most wicked civil war…is not treason to the United States.” In November, Dowell reached the University of Virginia, where the “beautiful” sights stirred memories of the past and hopes for the future. While antebellum professors had proclaimed “nullification, secession and treason,” he prayed they would now teach only “peace and loyalty.” Despite these hopes, most UVA faculty and alumni remained impenitent, and they were already working to reassert White supremacy.[12]

Most UVA Unionists sympathized with former Confederates, supporting sectional reconciliation over racial justice. A few, however, including Congressman Henry Winter Davis and federal commissioner and women’s suffragist Robert H. Shannon, refused to forget the “slaveholding treason.” Dowell joined their ranks, becoming a Radical Republican and an ardent supporter of Reconstruction. He believed the “rebel States [had] forfeited their rights under the Constitution,” and that Confederate leaders should be “tried for treason.” During the war, he had framed emancipation as a “military necessity” and only defended freedmen’s rights to “hold property” and “pursue their own happiness.” Now, he celebrated the Reconstruction amendments, which granted freedom, citizenship, and suffrage to African Americans. The right to vote, he argued, empowered former slaves to defend their freedom, making them “not only free in name but in fact.” He called for “equal justice South and North,” urging every state to root out its discriminatory laws. He insisted that all Americans possessed “equal legal rights,” and that the “poorest colored man in Georgia…has the same rights to a seat in the Georgia Legislature as the most exalted master.”[13]

Dowell also became a champion of women’s rights. In November 1864, he celebrated American women for their “patriotism and devotion to the Union” and expressed his willingness to “see one of them elected Chief Magistrate of the United States.” Four years later, he called for a women’s suffrage amendment, arguing that the right to vote would “decrease the many wrongs now inflicted upon them.” He defended the “eternal principles of equal rights before the law, without regard to race, color or sex.” America, he insisted, had “many women as learned as Queen Victoria,” and they would “make as good a President as Victoria does a Queen.” He saw “no good reason why they should not have the right to vote and to hold office.” In 1876, Dowell served as vice president for the Oregon State Woman Suffrage Association, which demanded “equal political rights,” “equal pay for equal work,” and “all the privileges of law enjoyed by [men].”[14]

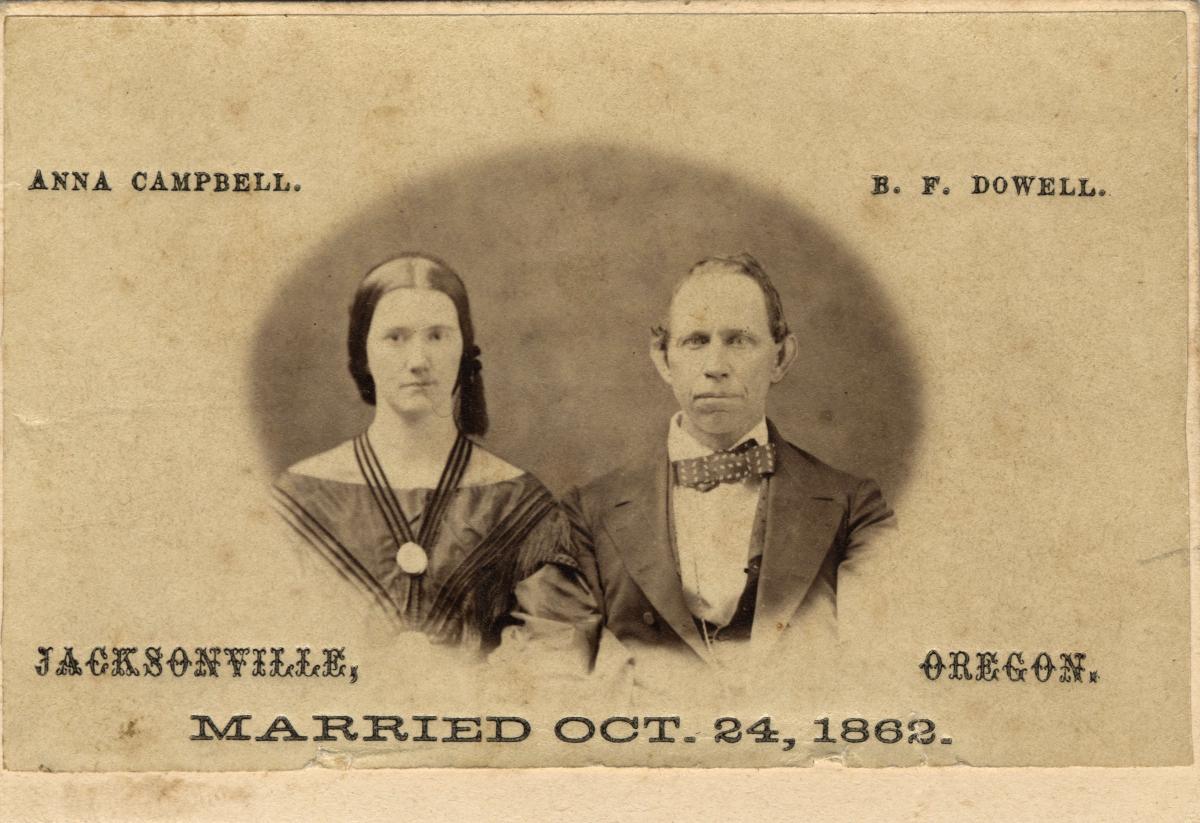

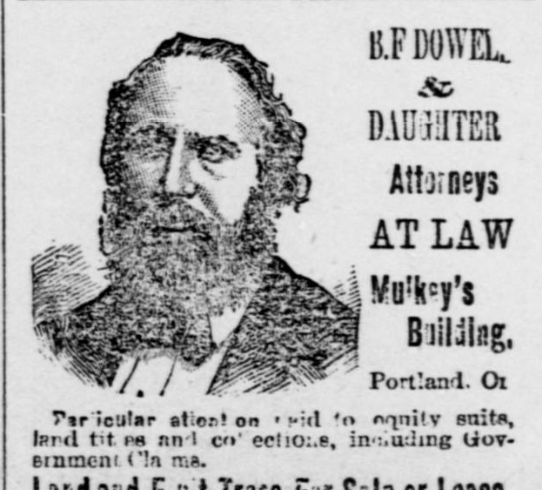

In small but significant ways, Dowell’s personal life reflected his commitment to these ideas. In 1862, he married Nancy Anna Campbell, a strong-willed, politically-savvy woman who played an active role in their community. She served on the Women’s Centennial Board, arranged meals for local July 4 celebrations, and presided over a “woman’s condolence meeting” after President James Garfield’s death in 1881. Nancy also supervised the Sentinel while her husband was away, occasionally editing and drafting articles for the newspaper. She shared her husband’s Republican principles and used her time as editor to wage an “aggressive campaign against the Democratic hosts that menaced her.” They gave their daughters, Fanchon and Anne, extensive educations, and in 1885, Anne began practicing law with her father. One writer praised Anne as a “young lady of rare mental grace,” and another declared her a “better lawyer than many of the male members of the profession.”[15]

Dowell sold the Sentinel in 1878, but he remained active in local Republican politics. He served in the Republican State Conventions of 1872, 1878, and 1880 and represented Oregon in the party’s 1872 national convention. He supported Benjamin Harrison’s presidential campaign in 1888 and spent the late 1880s writing articles for Republican newspapers across the state. He moved to Portland, Oregon, in 1885, and continued practicing law with Anne for the next several years. His health, however, deteriorated in the early 1890s, leaving him partially paralyzed and barely able to walk. Nearly destitute, he applied for a federal pension for his service in the Indian Wars. Before Congress could act, however, he died of pneumonia on March 12, 1897. Local editors eulogized him as an “old pioneer of Oregon” and “one of the best known members of the Oregon bar,” and Congress granted Nancy an $8 monthly pension soon afterward.[16]

Like many loyal Americans, Dowell had been a political moderate before the war. As the son of slaveholders, he decried Republican “Negro-ism,” defended the fugitive slave law, and sought to “keep peace between the North and South.” As late as April 1862, he called for “conciliation and compromise” and blamed abolitionists and secessionists alike for provoking the sectional crisis. The Civil War and its aftermath, however, steadily radicalized Dowell. By 1864, he embraced emancipation and “hard war.” After Appomattox, with Confederate “traitors” unrepentant, he championed Radical Reconstruction and demanded equal rights and equal justice for all Americans. His experience illustrates the Civil War’s transformative power, revealing the ways southern intransigence hardened northern resolve and embedded the ideals of biracial democracy in the American Constitution.

Images: (1) Benjamin F. Dowell, and (2) Benjamin and Nancy Ann Dowell (Oregon Historical Society Digital Collections); (3) Oregon Sentinel, May 27, 1865; (4) Ad, Oregon Sentinel, June 26, 1886.

Notes:

[1] On the culture of conservative Unionism, see Adam I. P. Smith, The Stormy Present: Conservatism and the Problem of Slavery in Northern Politics, 1846-1865 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Andrew F. Lang, A Contest of Civilizations: Exposing the Crisis of American Exceptionalism in the Civil War Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020); Jack Furniss, “States of the Union: The Rise and Fall of the Political Center in the Civil War North,” (PhD diss., University of Virginia, 2018); Matthew Mason, Apostle of Union: A Political Biography of Edward Everett (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

[2] Albemarle County, Virginia, 1830 United States Federal Census, available from www.ancestry.com; Tennessee, U.S., Early Tax List Records, 1783-1895, available from www.ancestry.com; Tennessee, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1779-2008, available from www.ancestry.com; Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia, Session of 1841-42 (Charlottesville: James Alexander, 1842); Session 18 of the University of Virginia Faculty Minutes, September 1, 1841 – July 4, 1842, available from www.juel.iath.virginia.edu; The Oregon Sentinel, 21 May 1879; History of the Pacific Northwest: Oregon and Washington, Vol. 2 (Portland, OR: North Pacific History Company, 1889), 305. Dowell’s paternal grandmother was Benjamin Franklin’s niece. In a passport application in 1867, Dowell listed his birthdate as October 31, 1826, and several 19th-century biographies used the same date. His tombstone, however, lists his birth year as 1821, and an obituary in the Portland Oregonian says he was born on October 31, 1821. The 1830, 1840, and 1860 census records all suggest a birth year between 1821 and 1825. His early biographies claim that he graduated from UVA in 1847--“before he was twenty-one years old.” His actual graduation, year, however, was 1842. If he was born in October 1826, then he would have graduated (with a law degree) at the age of 15. If, however, he was actually born in 1821, then he would have been 20 or 21 when he graduated, which seems more reasonable.

[3] History of the Pacific Northwest, 305; Franklyn Daniel Mahar, “Benjamin Franklin Dowell, 1826-1897: Claims Attorney and Newspaper Publisher in Southern Oregon” (MA Thesis, University of Oregon, 1964), 4-7; The Oregon Argus, 15 March 1856.

[4] History of the Pacific Northwest, 305; Mahar, “Benjamin Franklin Dowell,” 4-7; Benjamin F. Dowell to Samuel Dowell, 31 January 1856, Benjamin Franklin Dowell Journal and Letters, The Bancroft Library; Benjamin Franklin Dowell Narrative, The Bancroft Library. After a skirmish in August 1853, miners dragged a 9-year-old Native American boy through the streets of Jacksonville. As a gathering crowd shouted, “Hang him! Exterminate the Indian,” Dowell confronted the miners and urged them to stop. He removed the rope from the child’s neck and tried to lead him to safety, but to no avail. As he later recalled, the “mob rushed and took the Indian” and “held [Dowell] until the execution occurred.”

[5] Benjamin Franklin Dowel; Umpqua Gazette, 9 August 1855; The Oregonian, 30 June 1855; The Oregon Sentinel, 4 July 1857; Julian Hawthorne, The Story of Oregon: A History with Portraits and Biographies, Vol. II (New York: American Historical Publishing Company, 1892), 219; The Oregon Sentinel, 9 November 1867.

[6] History of the Pacific Northwest, 305; Benjamin Franklin Dowell Narrative; Benjamin F. Dowell to Samuel Dowell, 31 January 1856; Fred Blue, “Joseph Lane (1801-1881),” Oregon Encyclopedia, available from https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lane_joseph_1801_1881_/#.YDpynuhKg2x; Benjamin F. Dowell to Joseph Lane, August 1861, Joseph Lane Papers, Oregon Historical Society.

[7] The Weekly Oregon Statesman, 28 April 1862.

[8] Gary W. Gallagher, The Union War Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 1-6, 151-156; Gary W. Gallagher and Joan Waugh, The American War: A History of the Civil War Era (State College, PA: Spielvogel Books, 2015), 196; Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Ordeal of the Reunion: A New History of Reconstruction (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,) 271.

[9] Benjamin F. Dowell to Nathan Olney, 21 February 1865, Benjamin Franklin Dowell Papers, University of Oregon Libraries; The Oregon Sentinel, 16 July 1864, 27 August 1864, and 26 November 1864.

[10] The Oregon Sentinel, 26 November 1864.

[11] The Oregon Sentinel, 22 April 1865, 24 March 1866, 24 August 1867, 8 August 1868, and 7 November 1868.

[12] The Oregon Sentinel, 3 August 1867 and 28 December 1867; Peter S. Carmichael, The Last Generation: Young Virginians in Peace, War, and Reunion (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 222; Elizabeth R. Varon, "UVA and the History of Race: The Lost Cause Through Judge Duke's Eyes," UVA Today, 4 September 2019, available from https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-and-history-race-lost-cause-through-judge-dukes-eyes.

[13] The Oregon Sentinel, 14 March 1868, 5 December 1868, 20 February 1869, and 19 June 1869.

[14] The Oregon Sentinel, 26 November 1864, 20 February 1869; The New Northwest, 18 February 1876.

[15] The Oregon City Enterprise, 22 October 1875; The Oregon Sentinel, 18 June 1881, 7 June 1884, and 19 December 1885; The New Northwest, 6 October 1881; History of the Pacific Northwest, 307.

[16] The Corvallis Gazette-Times, 23 March 1872 and 30 March 1872; The Oregon Sentinel, 17 April 1878; The Oregonian, 14 March 1897; The Dallas Times-Mountaineer, 20 March 1897; “Nancy A. Dowell,” Senate Report No. 1494, 55th Congress, 3rd Session (1899).