Any moviegoer who has seen The Northman over the past month probably remembers the many animal motifs in the film. That’s true even if you’ve only seen the trailer, which includes ravens flocking to a misty island ruled by King Aurvandill War-Raven (Ethan Hawke) and a roaring Amleth the Bear-Wolf (Alexander Skarsgård) donning a snarling wolf pelt. Literature from the Viking Age frequently associated such animals with warfare — but it might surprise you to learn that a similar theme appears in sources from the American Civil War.

In the mid-twentieth century, scholars identified a pattern in Old English and Old Norse texts which they called the “beasts of battle.” Poets specifically called upon wolves, ravens, and eagles to raise a deathly aura and set the mood for tales of war. Here’s an example from Beowulf with the beasts boldened:

Many a spear

dawn-cold to the touch will be taken down

and waved on high; the swept harp

won't waken warriors, but the raven winging

darkly over the doomed will have news,

tidings for the eagle of how he hoked and ate,

how the wolf and he made short work of the dead.

The Beowulf beasts were gluttons of carrion, important not for any martial role but as signifiers that warriors will wage war. Other stories associate the warriors themselves with the beasts, such as the “wælwulfas” or “slaughter-wolves” (Vikings) in the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon.[1]

Consistent academic inquiry into Beowulf began during the nineteenth century, with the first translation to modern English appearing in 1835. No American publisher made the leap until 1882. Those who lived through the Civil War era, then, did not have much chance to model their writings and speeches after the Beowulf poet, or any similar Old English author. And yet, they did often invoke fearsome creatures in a similar way, using them to convey emotions ranging from rage to despair. Nineteenth-century Americans derived much of their wartime language from both ancient human attitudes about wildlife and the contemporary drive to wipe out large predators to maintain happy, secure, self-governing states. Animal references communicated perceptions of savagery, exacted verbal revenge or punishment, and laid out the necessary response to the enemy — premised upon ongoing campaigns of wildlife extirpation.

Some sources foreground carrion feasting, as in Beowulf. For example, take this excerpt from an anti-Copperhead oration: “The man who desires to have the Union as it was, ought to be hanged up by the heels until he be dead, dead, dead! and the wolves and ravens ought to eat the flesh from his carcass.” A preacher in Springfield, Ohio, apparently delivered this “war speech,” as the Alexandria Gazette called it, in September 1862. The Gazette sarcastically called Rev. Dr. Childs a “pious patriot,” while the North Branch Democrat in eastern Pennsylvania called him a “pious black republican.” The editors of the Democrat noted that many Republican men of similar abolitionist persuasion lived in their corner of the state, and continued, “We have no idea that we have any animals in these parts, that are beastly enough to touch their corrupt carcasses.” Assuredly, the emphasis was on the latter clause, not the former — the Pennsylvania mountains would remain a haven for wolves until the close of the century. In the war timeline, however, September 1862 was a critical month, witnessing the Battle of Antietam and President Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which Northern Democrats largely detested. Indeed, the North Branch Democrat preferred “the Union as it was,” as their coverage of the vituperative Childs speech endorsed. The same page that reprinted the speech denounced emancipation as the product of “insane ravings” from Horace Greeley, the anti-slavery editor of the New-York Tribune, and the paper also predicted that the effort would fail like that of John C. Frémont, the Union general whose early attempt at military emancipation Lincoln squashed.[2] Greeley himself had followed the beastly pattern as he pled for aggressive policy against Confederate slavery in his famous open letter to Lincoln the previous August, protesting that the administration had “fought wolves with the devices of sheep.”

Parallel to such anti-slavery invocations, pro-Confederate rhetoricians summoned beasts for their own purposes. In a defense of unforgiving living conditions at Confederate prisons, the Richmond Daily Dispatch cried, “[U.S. prisoners of war] came to exterminate us as beasts and brutes of the forest...We might have maimed and left them lying upon the ground, to become a living prey to wolves and buzzards.” This outburst came in February 1862, after only one campaigning season. Reminiscent of the ancient style, the writer conjured wolves and raptors feeding on dead soldiers — but with a political intent rather than as poetic epic. The passage also referenced the more modern practice of predator extirpation, a process of bounty hunting and agrarian sharpshooting that Americans had undertaken since the colonial era. Northern guns, said this Richmonder, had redirected from wolves and panthers to fellow men. That framing reversed the roles from an earlier Dispatch article, in which the paper exclaimed: “It is not men who are fighting us; it is wild beasts who are panting for our destruction, and whom we ought to exterminate, whenever we meet them, as we would wolves and panthers.”[3] Writers of the era articulated the shock of national sundering and civil violence by comparing both themselves and their enemies to hated wild creatures — they felt their humanity betrayed and returned the favor. When Confederates lambasted “Beast” [Benjamin] Butler, the pejorative was not just alliterative. Alleging the savagery of the Union general fit into a broader pattern of discourse concerning real wild beasts still living in the South.

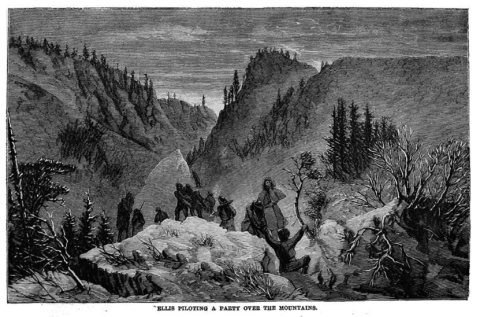

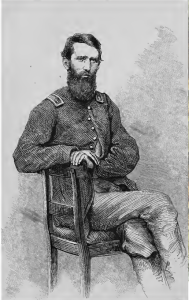

Southerners came in different stripes, of course, especially in east Tennessee. Daniel Ellis, a wagonmaker from Carter County, literally burned his bridges with the Confederacy and became a crucial aide to the Union cause in the mountains, where he served as a recruiter and guide. Known as the “old red fox” by frustrated Confederates, Ellis wrote a postwar memoir in which “beast” was one of his favorite words. Sometimes rebel raiders were “the ravenous wild beasts of the forest,” at other times the motif applied to Unionists:

“Little did I then imagine that...I, my neighbors, and my relatives, would be hunted and shot at like the wild beasts of the mountains, just because we were opposed to a mushroom ‘Southern Confederacy’ supplanting and annihilating the best form of government which has ever been devised…”

Maneuvering through the Tennessee highlands had familiarized Ellis with wolves, panthers, and bears, but the war with them paused as he and his own kind became the rifle’s target.[4]

In ecological terms, Ellis’s Appalachian Mountains shared certain characteristics with the Western and Trans-Mississippian theaters of the war. Here varmint extirpation efforts remained far from completion, so wolves and other predators tend to appear in the Official Records when the documents describe the fighting in places like Missouri and New Mexico. Confederates failed to pursue Colonel Franz Sigel after the rout at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, partly due to fear that wolves and coyotes would despoil their dead and wounded if their comrades did not attend to them.[5] But that possibility could also be a desecrating tool of war. In 1863, United States Brigadier General Henry Hastings Sibley reported success in his campaign to drive Dakota and Lakota peoples westward across Dakota Territory. This punitive expedition followed up on the bloody Dakota War from the previous year, the final battle of which took place the day after the announcement of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. While Sibley had not “extirpated” all of the warriors from the fiercest war bands, as he expressed was his preference, he was satisfied that “the bodies of many of the most guilty have been left unburied on the prairies, to be devoured by wolves and foxes.” His phrasing accidentally adjusted the Old English “beasts of battle” to the Great Plains context, and more purposely used animals to emphasize the perceived savagery of the Indian threat. The quote accompanies a more (in)famous offering from Major General John Pope, Sibley’s commanding officer and the embarrassment of Second Bull Run, who instructed Sibley to treat the Dakotas as “maniacs or wild beasts.”[6]

In ecological terms, Ellis’s Appalachian Mountains shared certain characteristics with the Western and Trans-Mississippian theaters of the war. Here varmint extirpation efforts remained far from completion, so wolves and other predators tend to appear in the Official Records when the documents describe the fighting in places like Missouri and New Mexico. Confederates failed to pursue Colonel Franz Sigel after the rout at Wilson’s Creek, Missouri, partly due to fear that wolves and coyotes would despoil their dead and wounded if their comrades did not attend to them.[5] But that possibility could also be a desecrating tool of war. In 1863, United States Brigadier General Henry Hastings Sibley reported success in his campaign to drive Dakota and Lakota peoples westward across Dakota Territory. This punitive expedition followed up on the bloody Dakota War from the previous year, the final battle of which took place the day after the announcement of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. While Sibley had not “extirpated” all of the warriors from the fiercest war bands, as he expressed was his preference, he was satisfied that “the bodies of many of the most guilty have been left unburied on the prairies, to be devoured by wolves and foxes.” His phrasing accidentally adjusted the Old English “beasts of battle” to the Great Plains context, and more purposely used animals to emphasize the perceived savagery of the Indian threat. The quote accompanies a more (in)famous offering from Major General John Pope, Sibley’s commanding officer and the embarrassment of Second Bull Run, who instructed Sibley to treat the Dakotas as “maniacs or wild beasts.”[6]

Americans who brought animals into their war stories did so under cultural norms and natural surroundings that widely differed from those of medieval bards. The biblical literacy of common Americans far surpassed that of Anglo-Saxon peasants, meaning that Christian scriptural interpretations of wolves played a more central role in Civil War era rhetoric — more on that another time. But wild predators could fulfill certain similar functions in the two societies, such as describing the horrible maw of the battlefield or animalistic perceptions of the enemy. And while culture changes, many of the raw materials for capturing the scene remained the same: soldiers, beasts, the trauma of war, and the need for a way to communicate about it all. The overlap in subject and form is not just a fun fact: it indicates the enduring ways that people across time and geography consistently seek to make sense of their lives and societies through their experiences and expectations of the natural world.

A little postscript: By the way, Daniel Ellis provides a serendipitous link between the Civil War and The Northman that this blog post simply could not ignore — his autobiography begins by quoting Hamlet (derived from the medieval Amleth story, as was the recent film) to remind Jefferson Davis that he would face judgment in Heaven if not on Earth.[7]

Author biography: Jeremy Nelson is studying environmental history with a focus on the Civil War Era, guided by Professor Caroline E. Janney. With roots in Hampton Roads, he graduated from Princeton University in 2020 with a bachelor’s degree in history, completing a pair of independent research projects on Virginia's Readjuster Party and on American meteorological disasters. His master’s thesis argues that the human devastation of the Civil War allowed a brief but significant recovery of ecosystems, especially in the Upper South.

Images: (1) "Ellis Piloting a Party over the Mountains," from Daniel Ellis, Thrilling Adventures of Daniel Ellis: The Great Union Guide of East Tennessee; (2) John J. Audubon’s depiction of the coyote or “prairie wolf” in The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, vol. II (1846, plate 71); (3) "Portrait of Daniel Ellis," from Ellis, Thrilling Adventures of Daniel Ellis.

[1] Thomas Honegger, “Form and Function: The Beasts of Battle Revisited,” English Studies 79, no. 4 (July 1, 1998): 290, https://doi.org/10.1080/00138389808599134; Seamus Heaney, translator, Beowulf, (Faber and Faber: Cambridge, England, London, 2007), ll. 3217–3223; for wælwulfas see the Old English Aerobics Glossary at http://glossary.oldenglishaerobics.net/, accessed May 8, 2022.

[2] Alexandria Gazette, September 4, 1862, 4, and North Branch Democrat, September 24, 1862, 2.

[3] Daily Dispatch, December 6, 1861, 2, and February 7, 1862, 2.

[4] Daniel Ellis, Thrilling Adventures of Daniel Ellis: The Great Union Guide of East Tennessee, (New York: Harper & Bros, 1867), 13, 190.

[5] O.R. Ser. 1, Vol. 22, Part 1, 358, and Staunton Spectator, December 10, 1861, 2.

[6] Pope’s quote in full: “The horrible massacres of women and children and the outrageous abuse of female prisoners, still alive, call for punishment beyond human power to inflict. There will be no peace in this region by virtue of treaties and Indian faith. It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so and even if it requires a campaign lasting the whole of next year. Destroy everything belonging to them and force them out to the plains, unless, as I suggest, you can capture them. They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made.”

[7] Ellis, Thrilling Adventures, 16.