This second of three installments on the Shenandoah Valley during the Civil War, which as a group anticipate our Signature Conference for 2017, focuses on military action. From the confrontation between Joseph E. Johnston and Robert Patterson during the campaign of First Bull Run through the Confederate defeat at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, almost continuous activity of some sort disturbed the Valley’s pastoral countryside. The region witnessed more than a dozen pitched battles, hundreds of skirmishes, and guerrilla operations carried out by John S. Mosby, John H. and Jesse McNeill, Harry Gilmor, and other partisan leaders that escalated in 1864 to the point of retaliatory hangings. The Army of Northern Virginia depended on secure lines of supply in the Valley during Robert E. Lee’s invasions of the United States in 1862 and 1863, campaigns that included significant clashes at Harpers Ferry and Second Winchester respectively. As part of Ulysses S. Grant’s grand offensive in the spring of 1864, a small army under Franz Sigel marched up the Valley to New Market, where a Confederate force that included cadets from V.M.I. stopped the Federals.

Two campaigns, both broadly framed by Robert E. Lee, stand out as most important--those conducted by Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson between March and June 1862 and by Jubal A. Early between June and October 1864. Easily the more famous—though not the more important--of the pair, Jackson’s sought to create a strategic diversion in the Valley that would immobilize Federal troops otherwise destined to reinforce George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac as it advanced against Richmond. With a force of approximately 17,500, Jackson confronted a series of Union commanders, including the minimally gifted Nathaniel P. Banks and John C. Frémont, and won victories at McDowell (May 8), Front Royal (May 23), First Winchester (May 25), Cross Keys (June 8) and Port Republic (June 9). Jackson pinned down Banks and Frémont and also convinced Federal planners to hold troops at Fredericksburg under Irvin McDowell, thereby denying McClellan thousands of reinforcements. He prevailed through rapid movement, deception, intimate knowledge of the Valley's geography (supplied by his brilliant cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss), and a willingness to take risks. None of Jackson’s battles was tactically impressive; indeed, his army struggled despite having superior numbers at McDowell and again at Port Republic. Still, these small victories reached a Confederate populace starved for good news from the military front. A string of disasters had befallen rebel arms in the Western Theater between February and late May 1862, and McClellan had reached Richmond's outskirts. The timing of Jackson's successes in the Valley thus could not have been more opportune, and the Confederate people responded by making Stonewall a transcendent hero. Had Richmond fallen to McClellan, however, the 1862 Valley campaign would be remembered as little more than an interesting sideshow.

Two years later, Lee selected Early to lead another operation in the Valley. With Grant's forces pressing close to the defenses of Richmond in early June, Lee laid out a range of goals. Early was to prevent troops under David Hunter from capturing Lynchburg, then to march down the Valley clearing it of Federals, and, finally, to cross the Potomac River and threaten Washington. Early accomplished all Lee asked, defeating Hunter at Lynchburg on June 18-19, moving into Maryland and vanquishing Federals under Lew Wallace at the Monocacy on July 9, and reaching the northern defenses of Washington, where Abraham Lincoln briefly came under fire, two days later. Unable to force his way into the city, Early withdrew to Berryville in the lower Valley, offering a typically salty assessment as his troops began their march back to Virginia: "We haven't taken Washington, but we've scared Abe Lincoln like hell!"

Two years later, Lee selected Early to lead another operation in the Valley. With Grant's forces pressing close to the defenses of Richmond in early June, Lee laid out a range of goals. Early was to prevent troops under David Hunter from capturing Lynchburg, then to march down the Valley clearing it of Federals, and, finally, to cross the Potomac River and threaten Washington. Early accomplished all Lee asked, defeating Hunter at Lynchburg on June 18-19, moving into Maryland and vanquishing Federals under Lew Wallace at the Monocacy on July 9, and reaching the northern defenses of Washington, where Abraham Lincoln briefly came under fire, two days later. Unable to force his way into the city, Early withdrew to Berryville in the lower Valley, offering a typically salty assessment as his troops began their march back to Virginia: "We haven't taken Washington, but we've scared Abe Lincoln like hell!"

After a Union debacle at Second Kernstown on July 24 and the burning of Chambersburg. Pennsylvania, by southern cavalry on July 30, Grant assigned Philip H. Sheridan the task of crushing Early and destroying the Valley as a rebel granary. “If the war is to last another year,” Grant instructed his lieutenant, “we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.” Sheridan built an army of more than 40,000 men to oppose Early's 12-15,000 and brought the 1864 Valley campaign to a climax with smashing victories at Third Winchester (September 19), Fisher’s Hill (September 22), Tom’s Brook (October 9), and Cedar Creek (October 19). Between Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek, Sheridan’s troops also laid a heavy hand on significant stretches of the Valley in what residents bitterly termed “The Burning.” Sheridan’s victories helped re-elect Lincoln and other Republicans in November 1864, and the Confederacy never again used the Valley as a route of invasion or as a vital source of foodstuffs and livestock. Our next installment will focus on how the war affected civilians in the Valley.

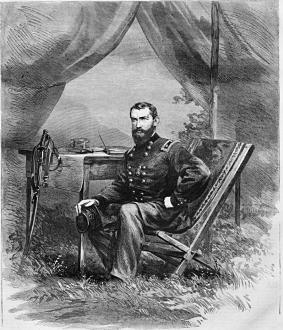

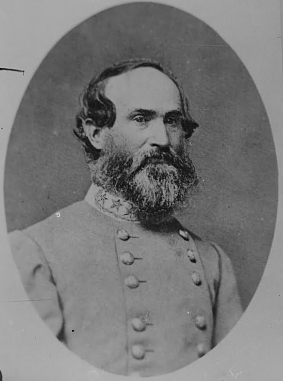

Images: Union General Philip H. Sheridan (Harper’s Weekly, October 8, 1864, cover) and his Confederate counterpart, General Jubal A. Early (Library of Congress).