Historians have neglected what regimental histories can reveal about the experience of common soldiers during the Civil War. Many in number, regimental histories provide an accurate portrait of the life of the Union soldier during the conflict and also comment on why soldiers went to war.

Between 1863 and 1921, Union soldiers wrote and published between 500 and 600 regimental histories. These books sought to document the experience of military service during the Civil War, taking as their reference the activities of individual regiments. While companies formed the building blocks of Civil War units, soldiers identified primarily with their regiments. Organized by state, and often encompassing companies from neighboring localities, regiments served as the backbone of the Civil War armies. Thus, for many soldiers, a history of the regiment told not only the story of their activities in the war but also that of their community.

Until recently, scholars have largely overlooked regimental histories as windows in the experience of common soldiers. One historian has indicted regimental histories as "simultaneously antiquarian and heroic" and suffering from a "narrow focus and celebratory tone." To be sure, many regimental histories do exhibit these traits. For instance, George N. Carpenter, in his History of the Eighth Regiment Vermont Volunteers, explained that "the book deals solely with the creditable deeds of officers and privates, and, on the ground that nothing else deserves to be preserved in such permanent form, consigns all else to oblivion." Carpenter, and others, expunged what they saw as negative and discreditable deeds from their works.

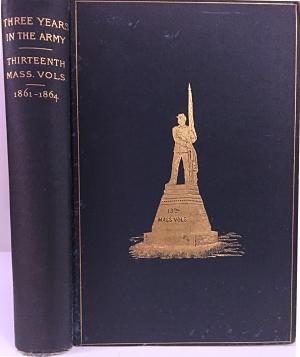

Yet while Carpenter elided unfavorable incidents from his account, other authors sought to tell a more complete story of their war. The committee that wrote The Story of the Fifty-Fifth Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War remarked that "it should be safe to abate somewhat of the usual indiscriminate and turgid eulogy" and "that the revealing of truth and not its suppression is the proper purpose of history." Likewise, in history of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Charles E. Davis, Jr., noted: "The opinions and judgments expressed are believed to be shared by a majority of the regiment during its service" and apologized "as we were no wiser than the rest of mankind at eighteen to twenty years of age, some of the statements may seem very crude in light of present information." Tellingly, regimental histories that sought to tell the story of the war warts and all outnumber the sanitized ones. As with any historical source, however, regimental histories demand to be weighed against other sources.

Regimental historians typically aimed to write accurate accounts of their units. Often they relied upon their personal experiences, but they also acted as historians. They drew upon diaries, official reports, letters, newspaper articles, and other primary source materials. In The History of the Twenty-First Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, Captain Charles F. Walcott noted that he examined reports, hospital records of the regimental surgeon, the recollections of the regimental Sergeant-Major, as well as "carefully-collated statements and diaries of several officers and men…given credit in text and notes from time to time." As modern historians do, many regimental historians collected primary source material, weighed the evidence, and placed disparate accounts into conversation and context.

To be sure, regimental histories often include ponderous accounts of marches, camp life, and the often mundane existence of the common soldier. Yet soldiers found value in recounting the minutiae of their life in the service precisely because they connected their experiences to the greater cause of the war. J. A. Mowris, surgeon of the 117th New York Infantry Regiment, wrote that the deeds of Union soldiers had to be remembered because they told the story of "the significance of our late triumph over the Slave-holders' Rebellion" and reminded readers of "the halo of that glorious era in our Nation's progress." His regimental history, laden with accounts of marches, camp, and battle, connected even minor episodes of daily life to monumental struggle to preserve the Union against the machinations of slaveholders.

Mowris, in identifying slavery as the cause of the Civil War, was not alone. Other regimental historians peppered their books with trenchant political observations. The historian of the 75the Illinois Infantry Regiment, for example, proclaimed that "our army fought for the maintenance of the Union" and "that emancipation of the negro and the fulfillment of the promises of the Declaration of Independence were the conditions of our national safety." While some regimental histories avoided opining on the politics of the time, most make clear why soldiers fought in the Union army. They believed it was precisely the justice of their cause that ensured their victory and demanded remembrance.

Although veterans stood as the primary consumers of regimental histories, evidence suggests that members of the general public found the books interesting and useful. Boston Gardner, in a letter to the author of a history of the 105th Ohio Infantry Regiment, recalled that "some years ago I read quite a number of war stories in Century Magazine" including those "written by Gen. U.S. Grant." He found the regimental history "better written and more interesting." The magazine articles, in his opinion, "were more like dry skeletons" while the regimental history was "a skeleton clothed with a beautiful form." Gardner suggests that contemporary readers found that these accounts had much to offer. The modern historian should take note.

Peter C. Luebke received his PhD in history from the University of Virginia in 2014. He is currently a documentary editor working for the Naval History and Heritage Command.

[Image: Board and spine decoration of Three Years in the Army: The Story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers from July 16, 1861 to August 1, 1864 by Charles E. Davis, Jr. (Boston: Estes and Lauriat, 1894).]